The Dukes Cut...

The Bridgewater Canal

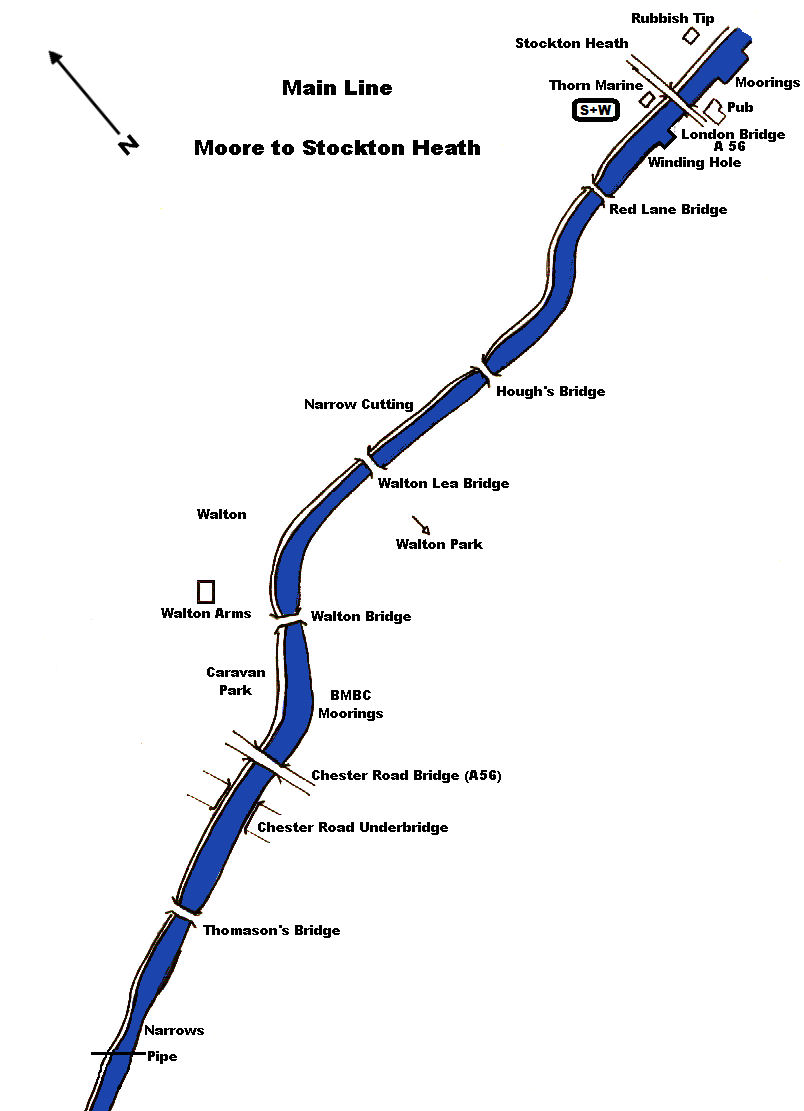

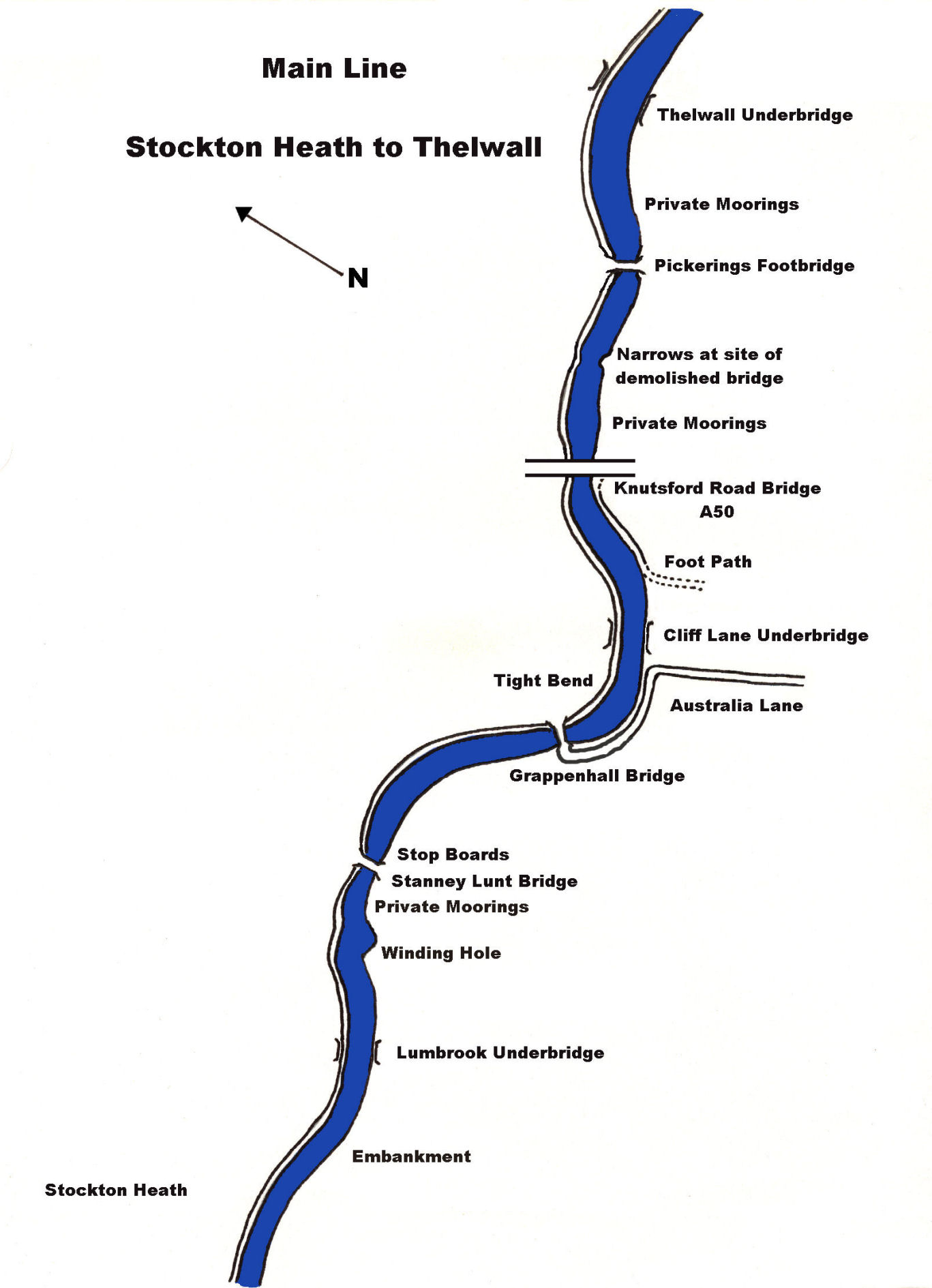

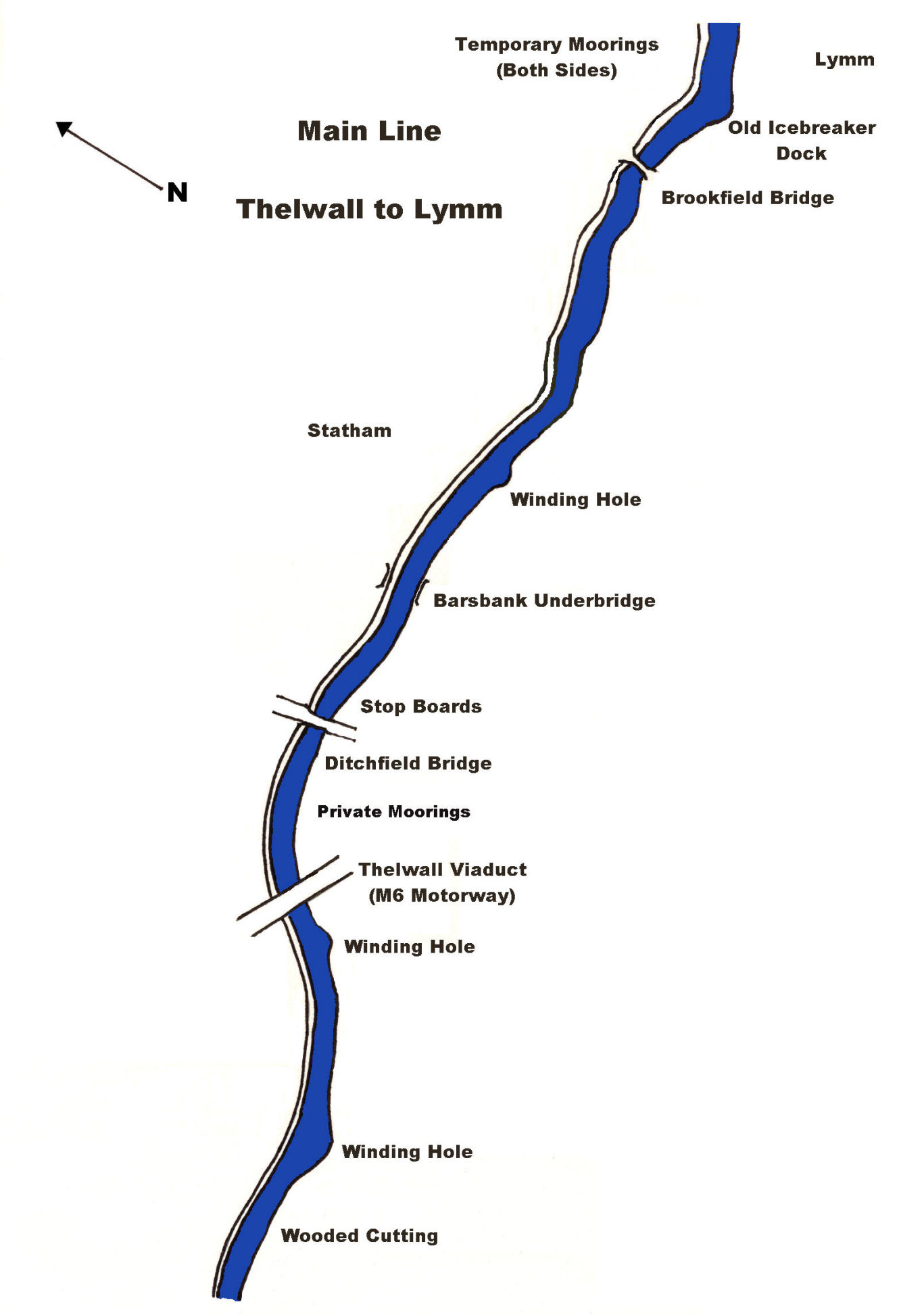

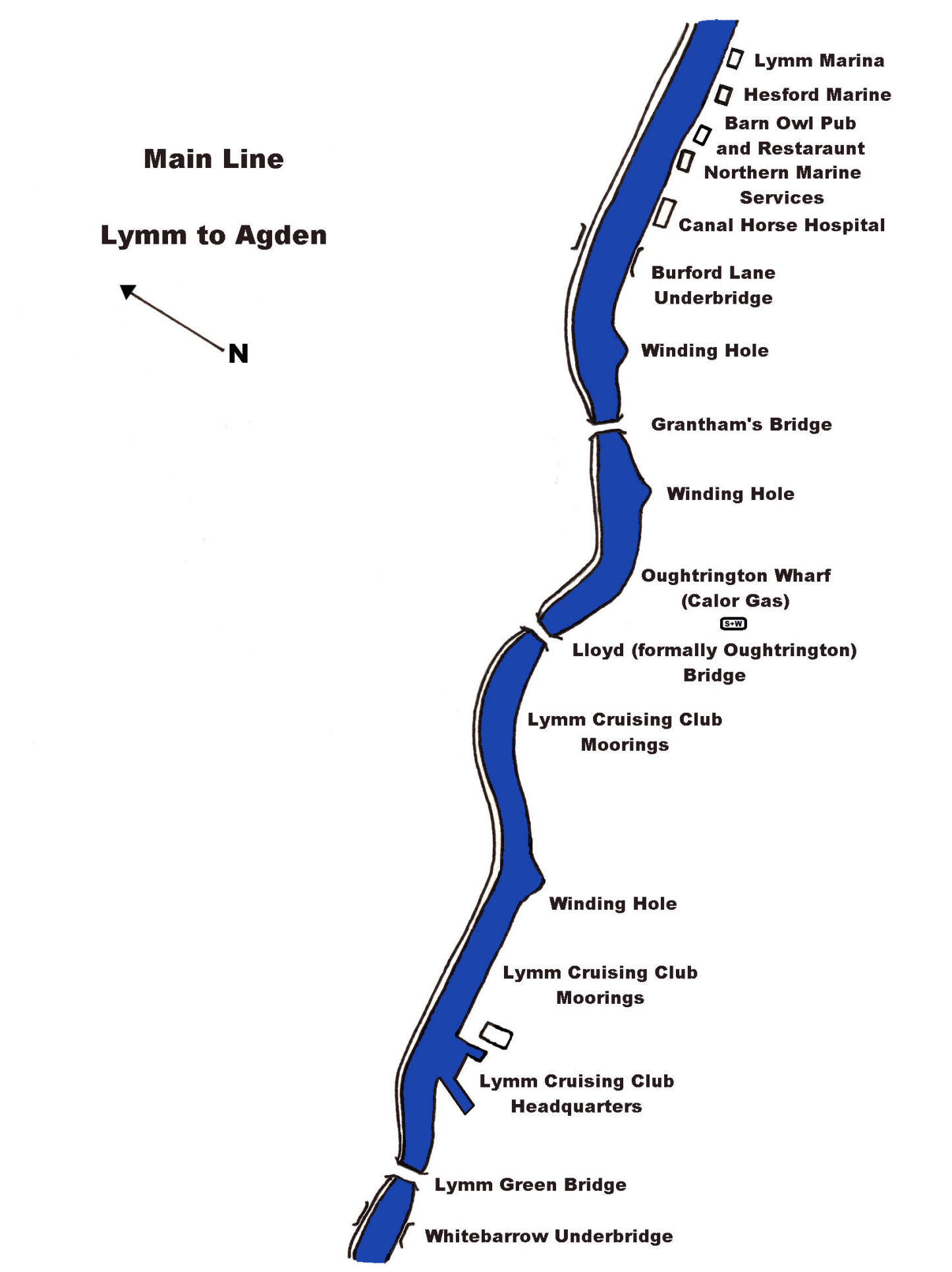

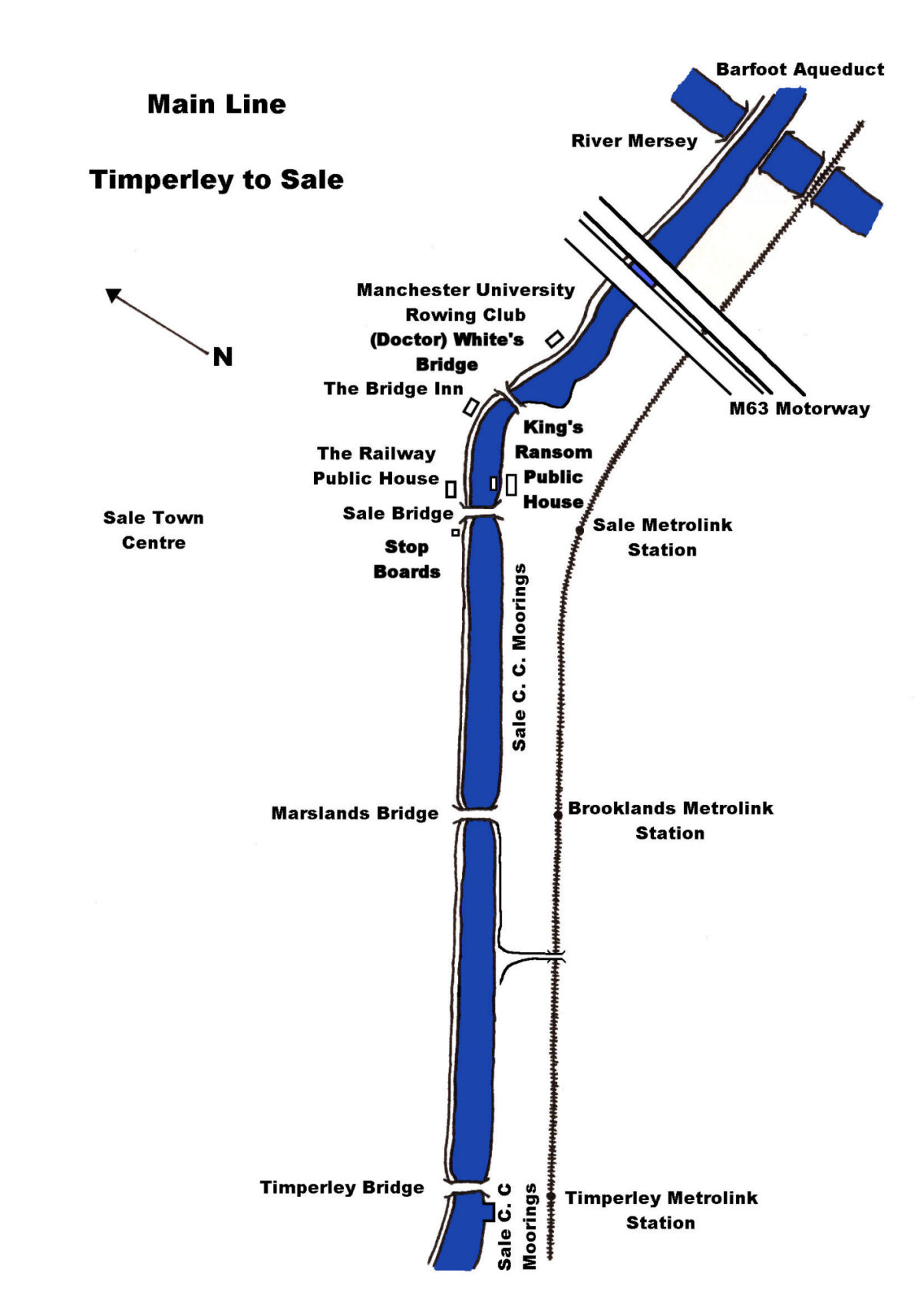

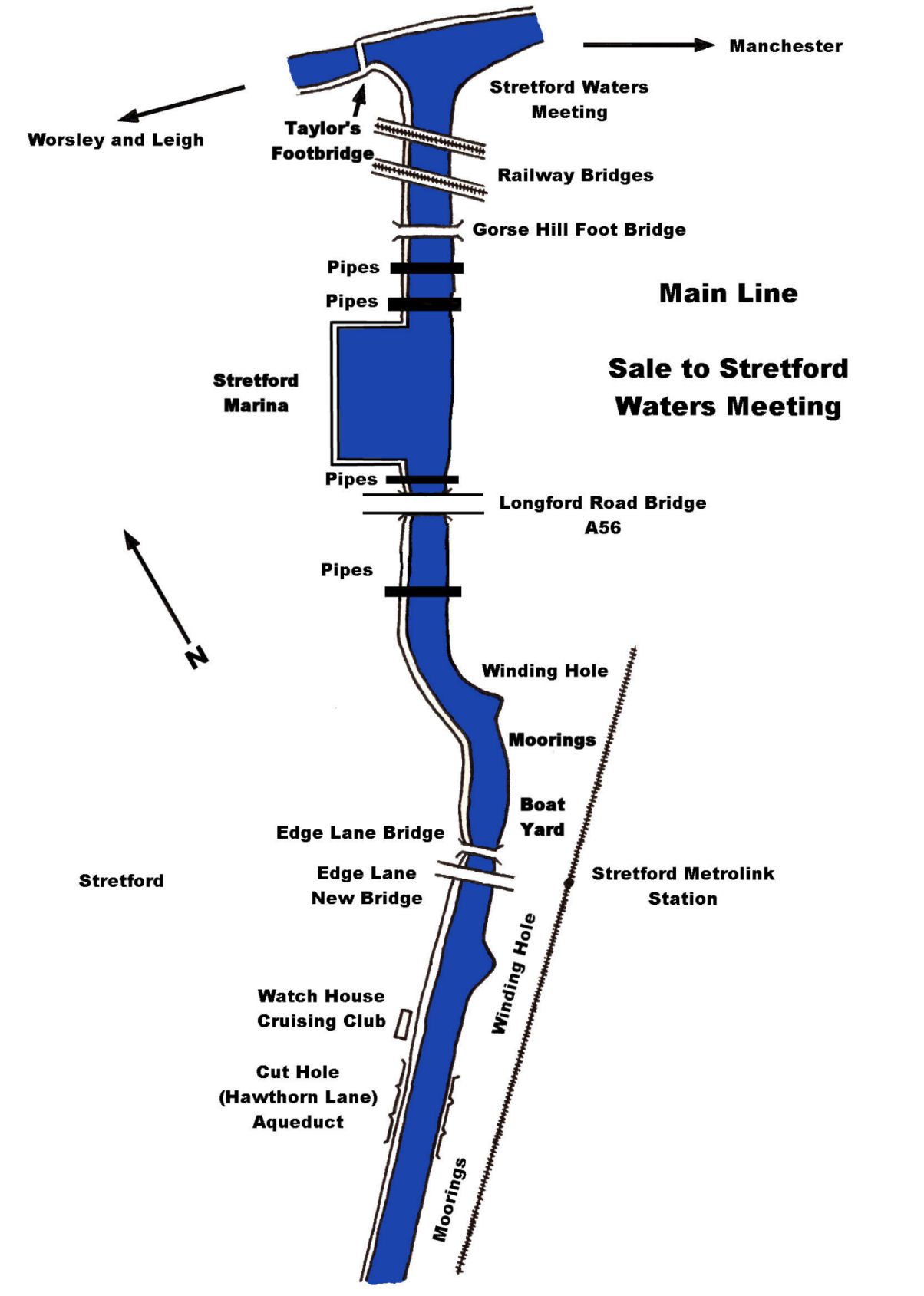

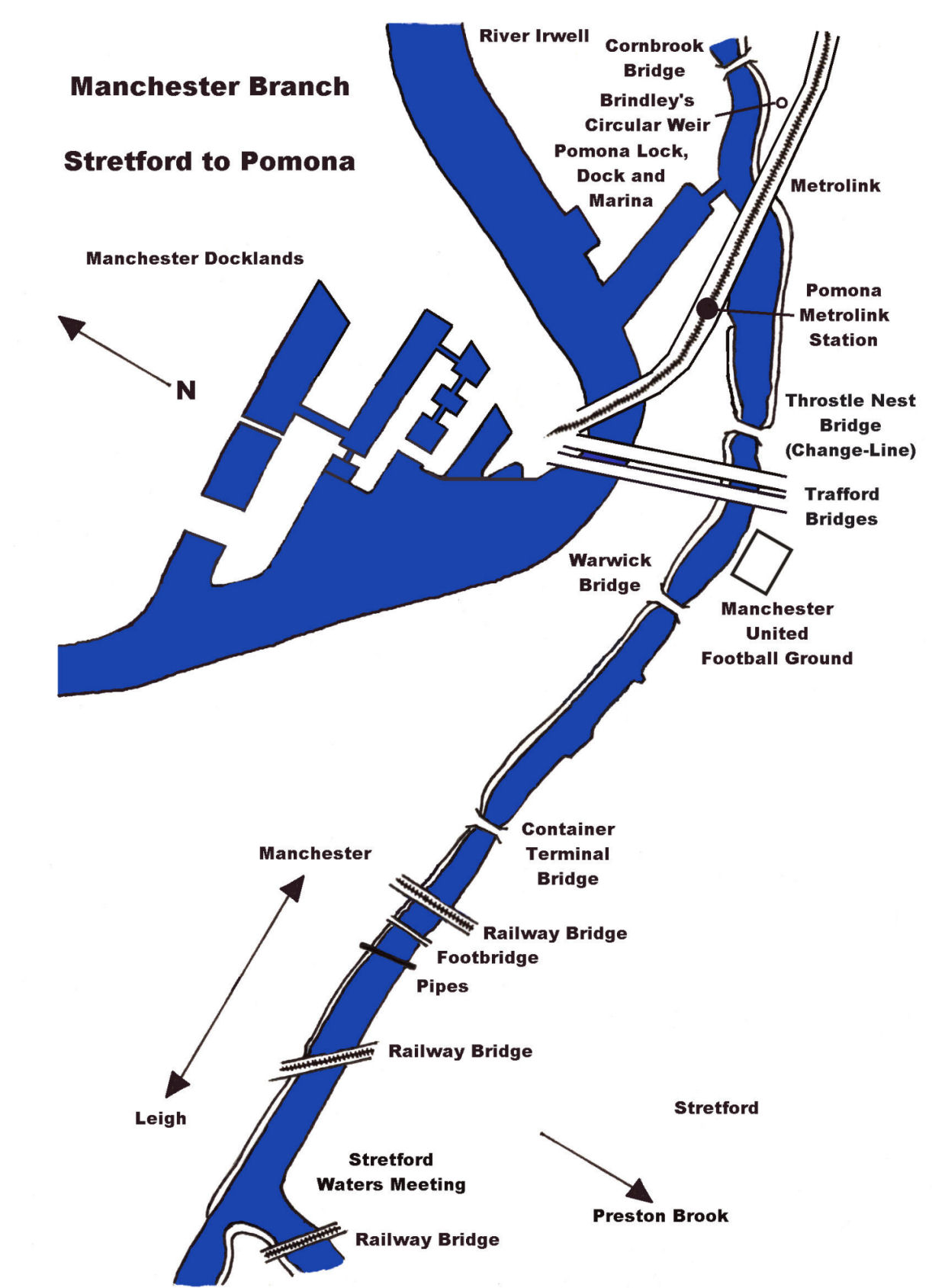

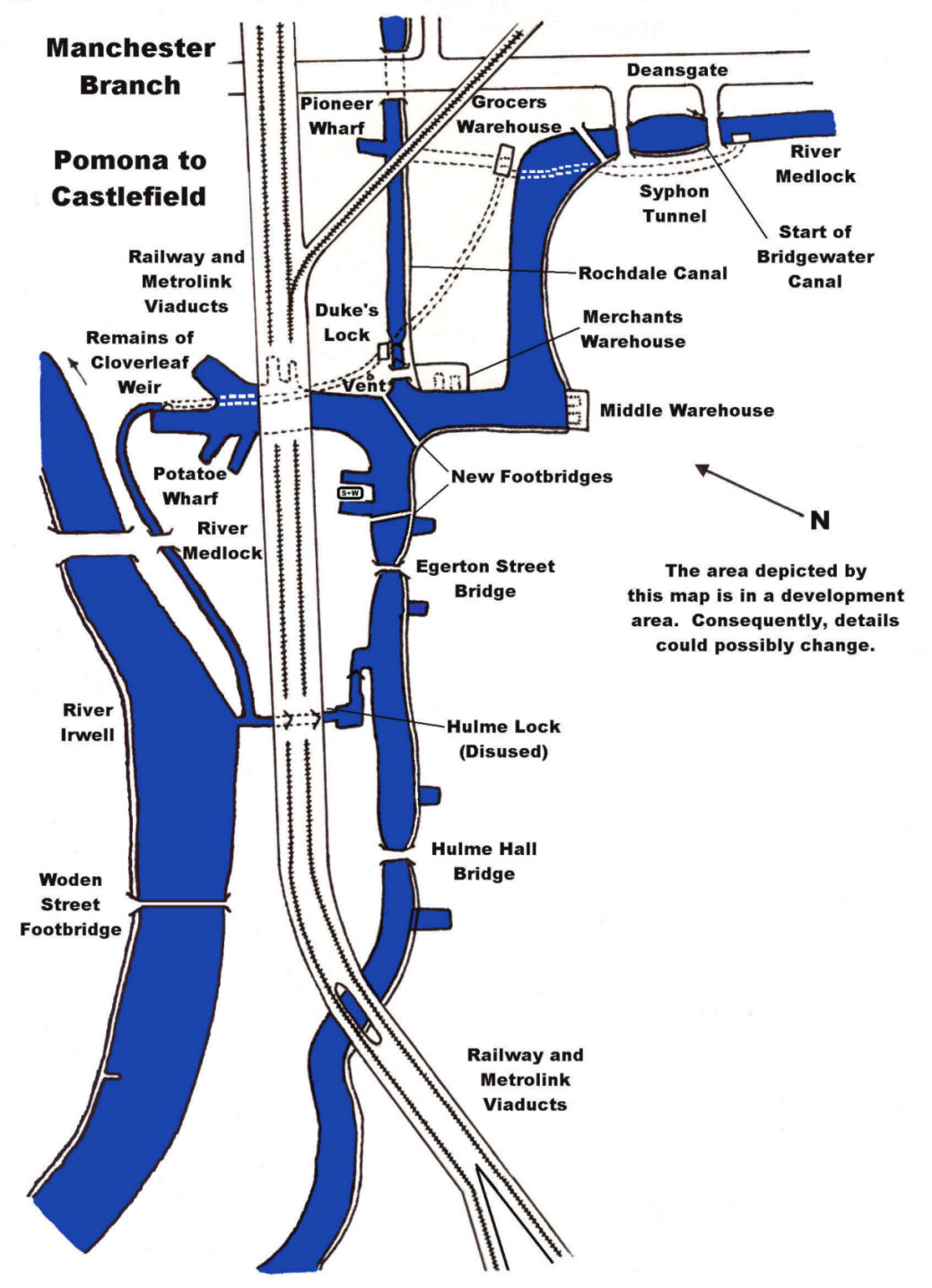

A unique portrait of the

Bridgewater Canal, both past and present, in words and photographs

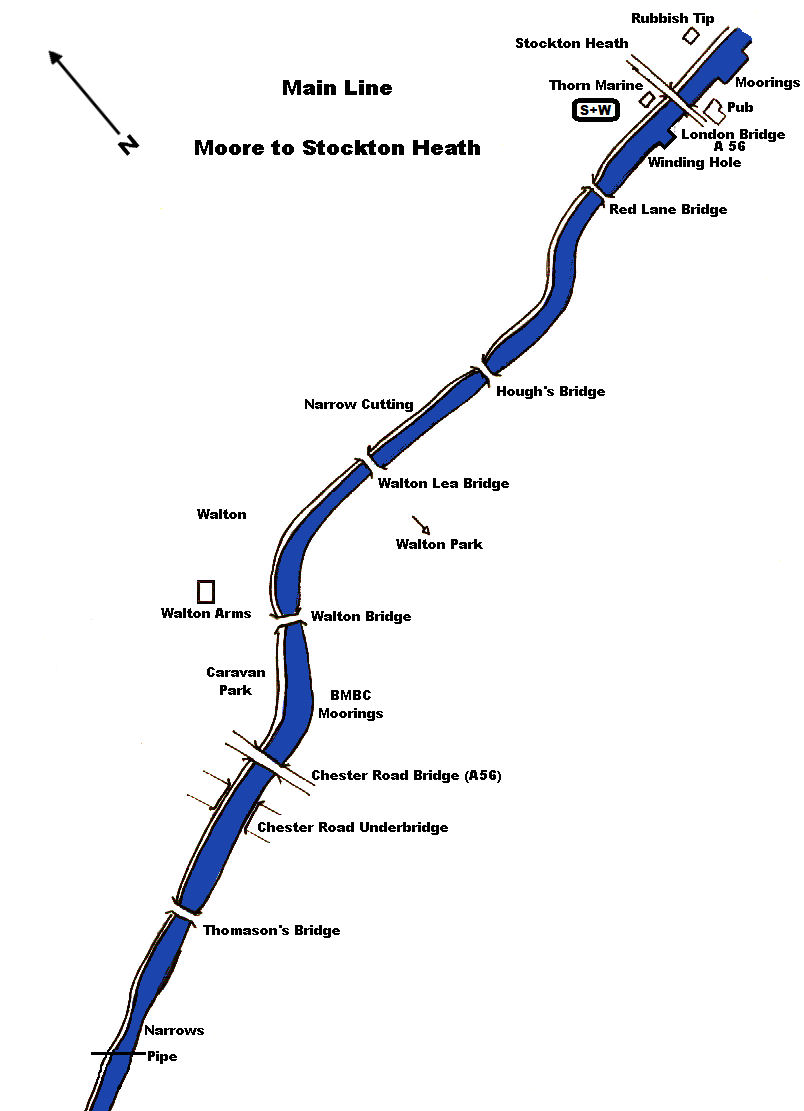

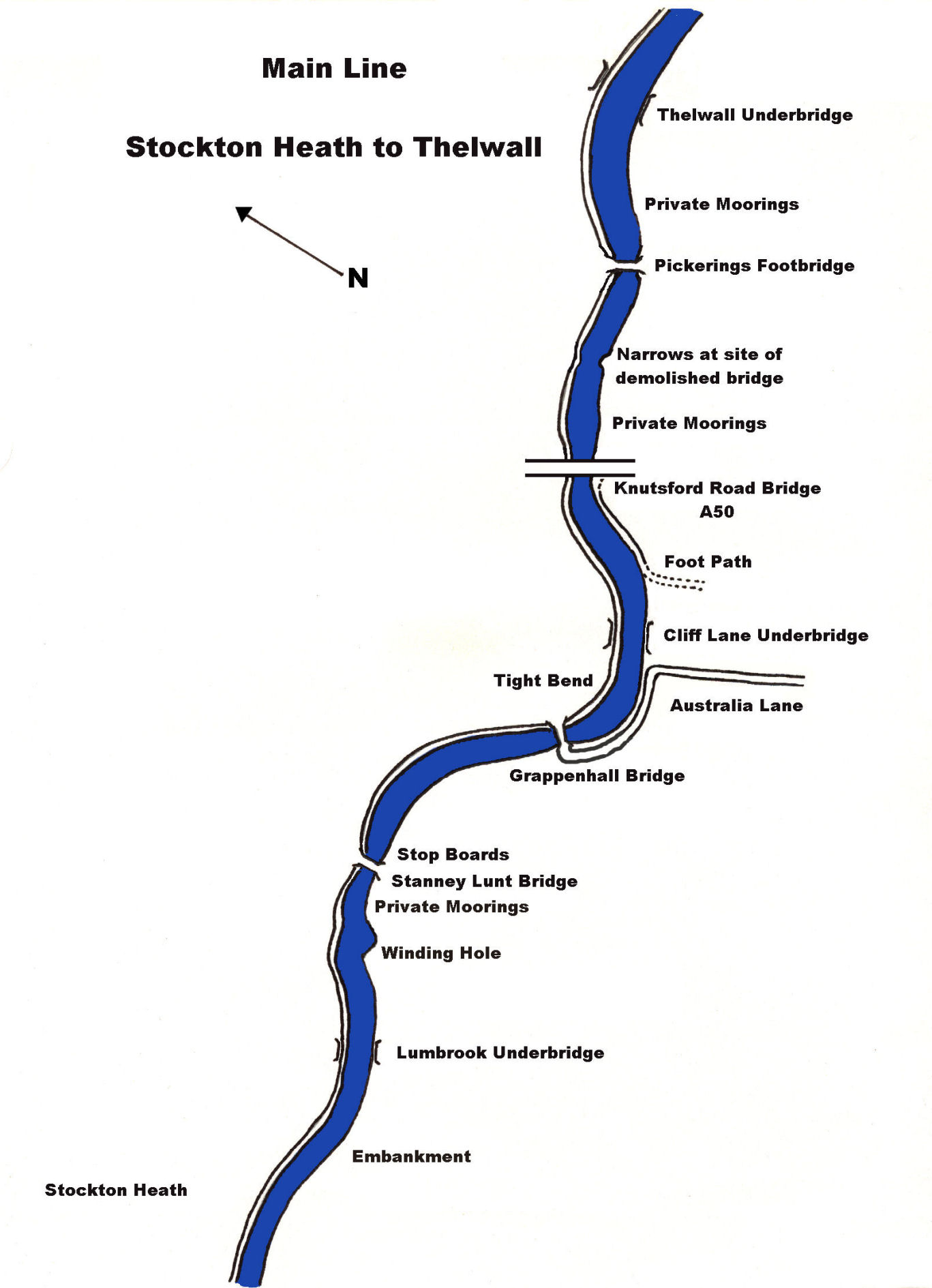

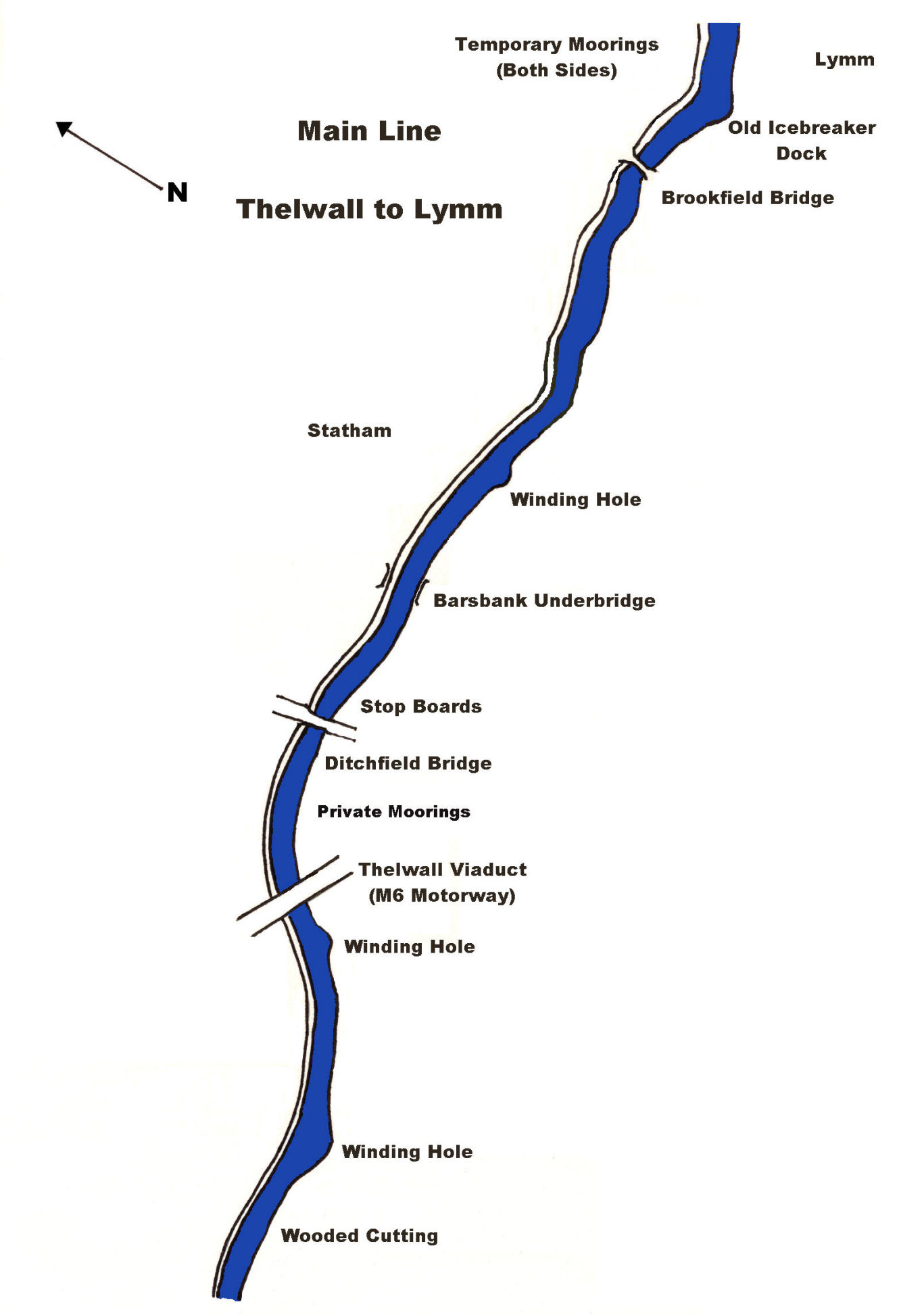

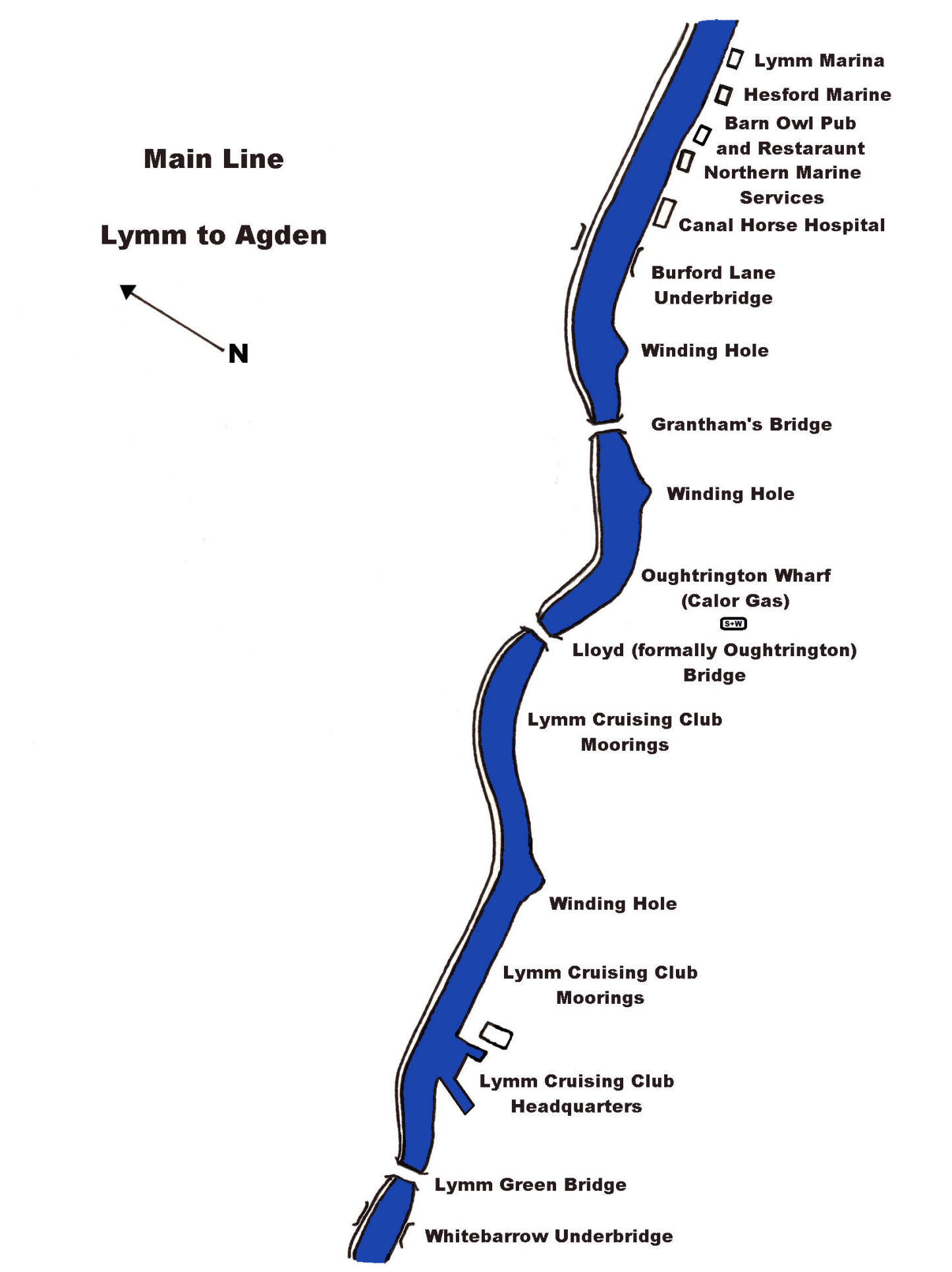

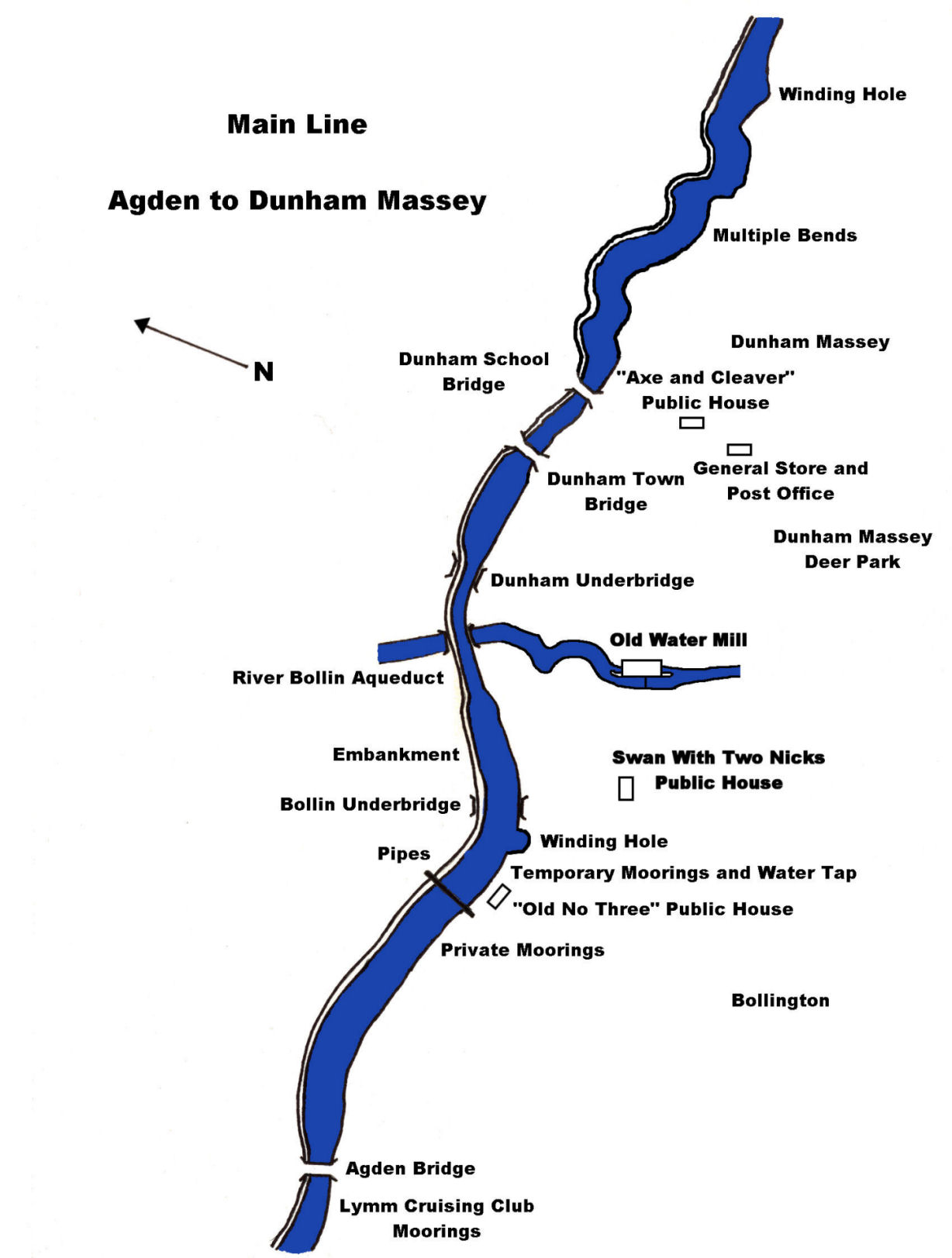

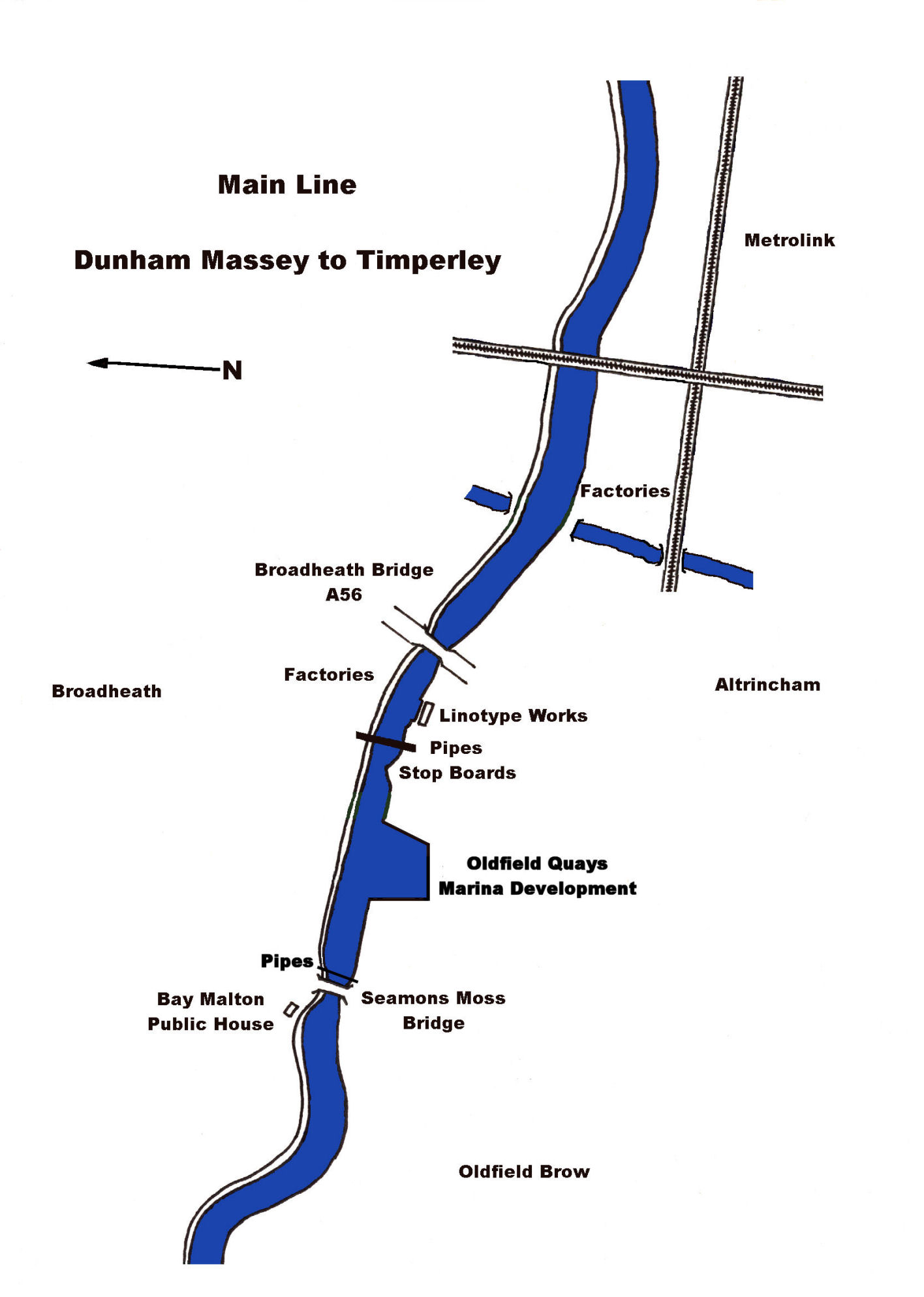

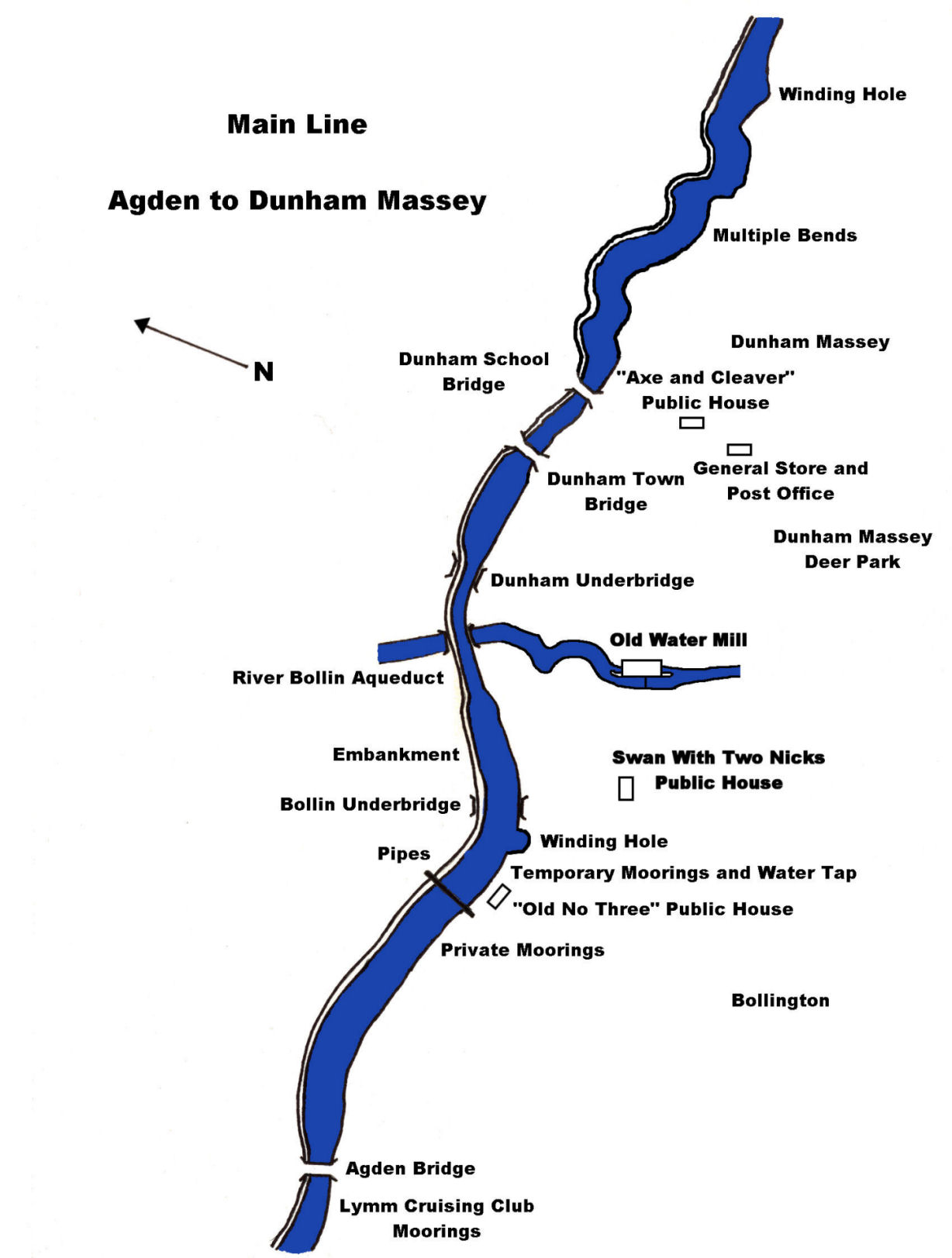

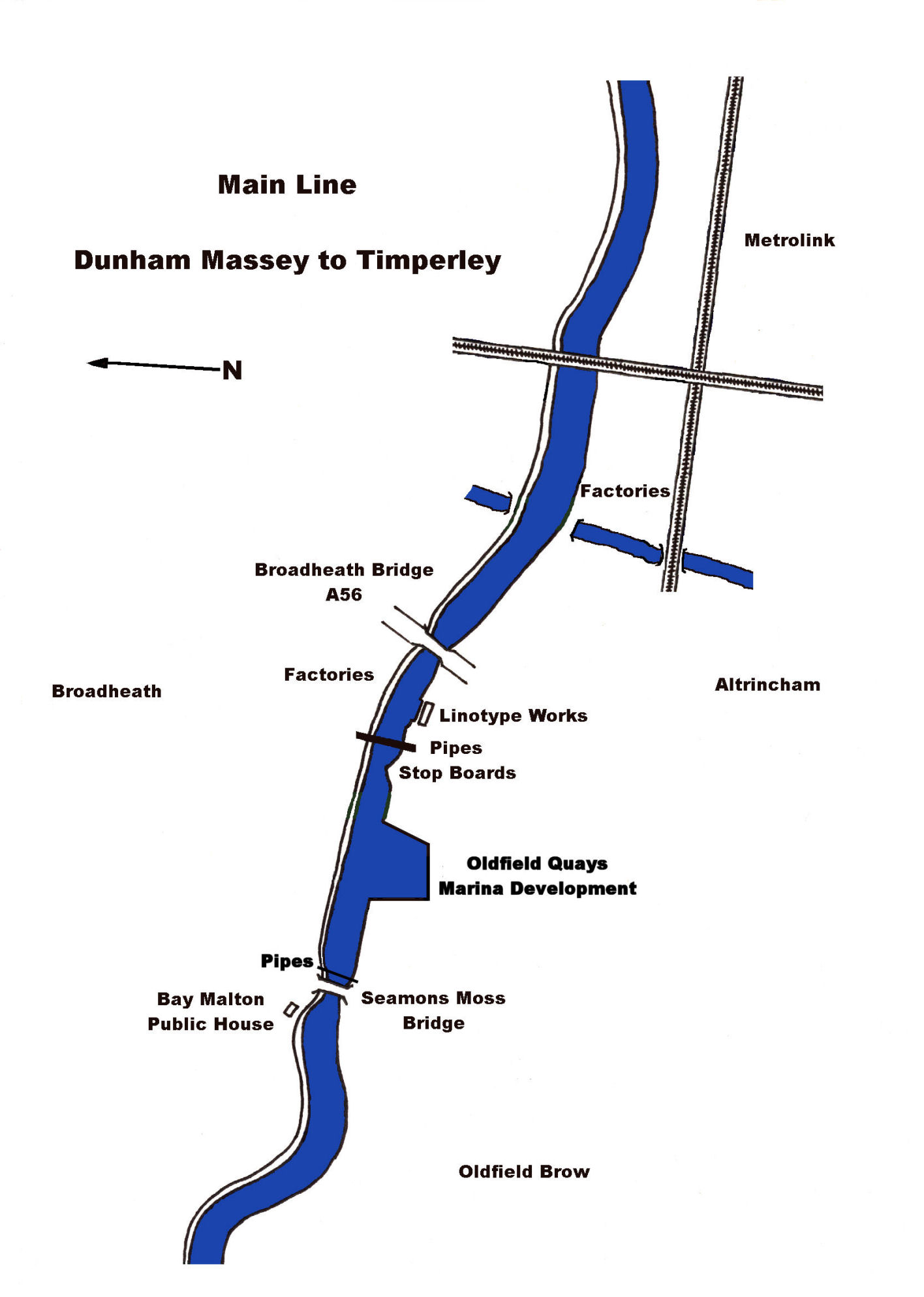

complete with an

accurate, up to date set of linear maps plus navigational information.

An

expanded

version of the History Press (formally Tempus) book by Cyril J Wood published here in eBook format

Introduction

I have been

interested in canals and inland waterways since a child when my parents

hired canal cruisers on the Shropshire Union and

Llangollen Canals

before having a boat of their own built. I followed their example, bought my

first boat in 1983 and moored it on the

Shropshire Union

Canal at Beeston Iron Lock

before moving to the

Bridgewater

Canal in 1985. I was already aware

of the historical impact that this canal had made on inland navigation in

this country having attended

a meeting of the Manchester Branch of the I.W.A. in

1967 which

featured a talk given by the late

Frank Mullineux... the well known Bridgewater Canal Historian, on the

Worsley Mines. The information that I gained at this lecture was to sow the

seed for my appreciation and love of the Bridgewater Canal.

The more I cruised the

Bridgewater Canal

the more I appreciated its history

and

diversity.

I started to

photograph the canal and give audio/visual presentations about it to various

interested societies. In 1987 I decided to write a commentary for the A/V

presentation. This graduated into relating the canal's history as well as

describing the route and its features. I then mapped the whole canal and

combined them with the photographs and text with a view to having the finished work published

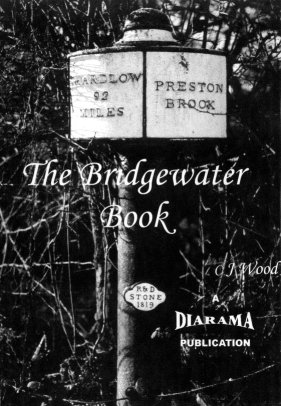

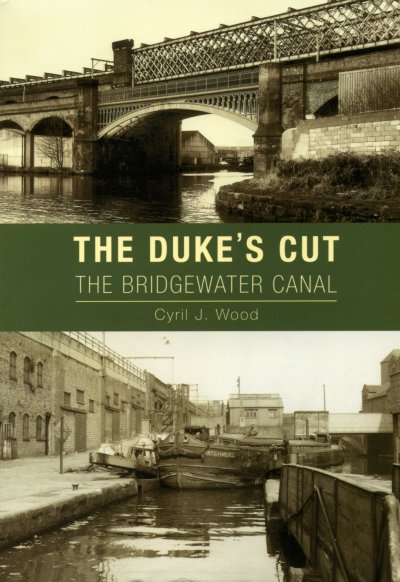

as "The Bridgewater Book" the front cover of which is illustrated below. For

various reasons this project was shelved and resurrected in 2000 as "The

Duke's Cut - The Bridgewater Canal". It was subsequently published by Tempus

Publishing the following year. It would

be very pretentious of me to say that this is the definitive publication on

the canal as each book has its own individuality and focuses on different

aspects of the canal. I have tried to produce a book that concentrates of

the “mechanics” of the canal’s history and geography concisely and without

the encumbrance of facts that the reader usually skips.

I hope that

you, the reader, gain as much enjoyment out of reading this book as I have

had producing it and that you find it a readable, informative and

entertaining piece of work that relates the canal’s history, describes it’s

route, gives invaluable information to those wishing to use it and documents

the canal with photographs of features are familiar, that have disappeared

and places that have changed beyond recognition.

I have

tried to keep abreast of changes to the canal but I apologize for any

mistakes or inaccuracies that (inevitably) may have crept into the text,

maps or photographs in this book.

The front cover of "The Bridgewater Book"... precursor to "The Duke's Cut -

The Bridgewater Canal"

Preface to the eBook Version

Producing

an eBook (and web) version of "The Duke's Cut - The Bridgewater Canal" provides me

with the luxury of laying out the manuscript

in the

way

that I first envisaged it. That is to say having the text, photographs and

maps in the places that I would like rather than the publisher's

preferences (who I have to say have done a good job of it anyway). I have

not had to make many up-dates or changes to this book since the Second

Edition was released in June 2009. The only significant differences between

this and the preceding editions

are the layout, some additional photographs of the canal,

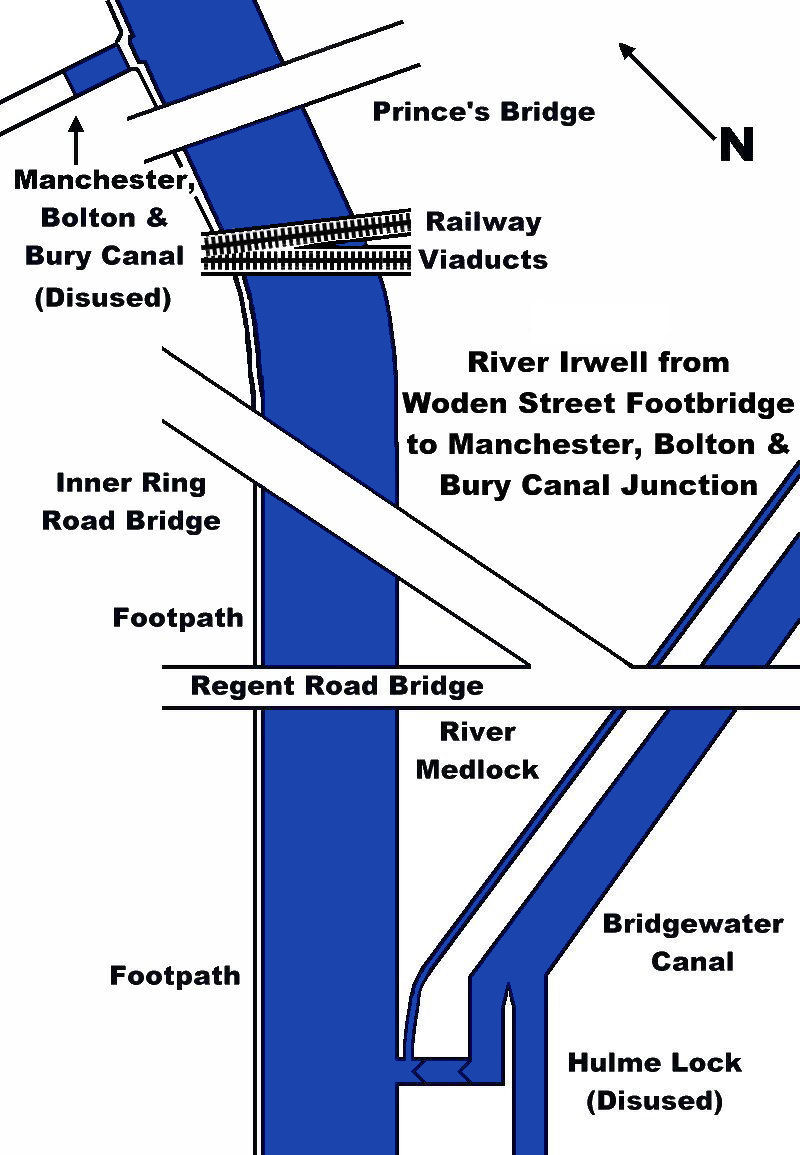

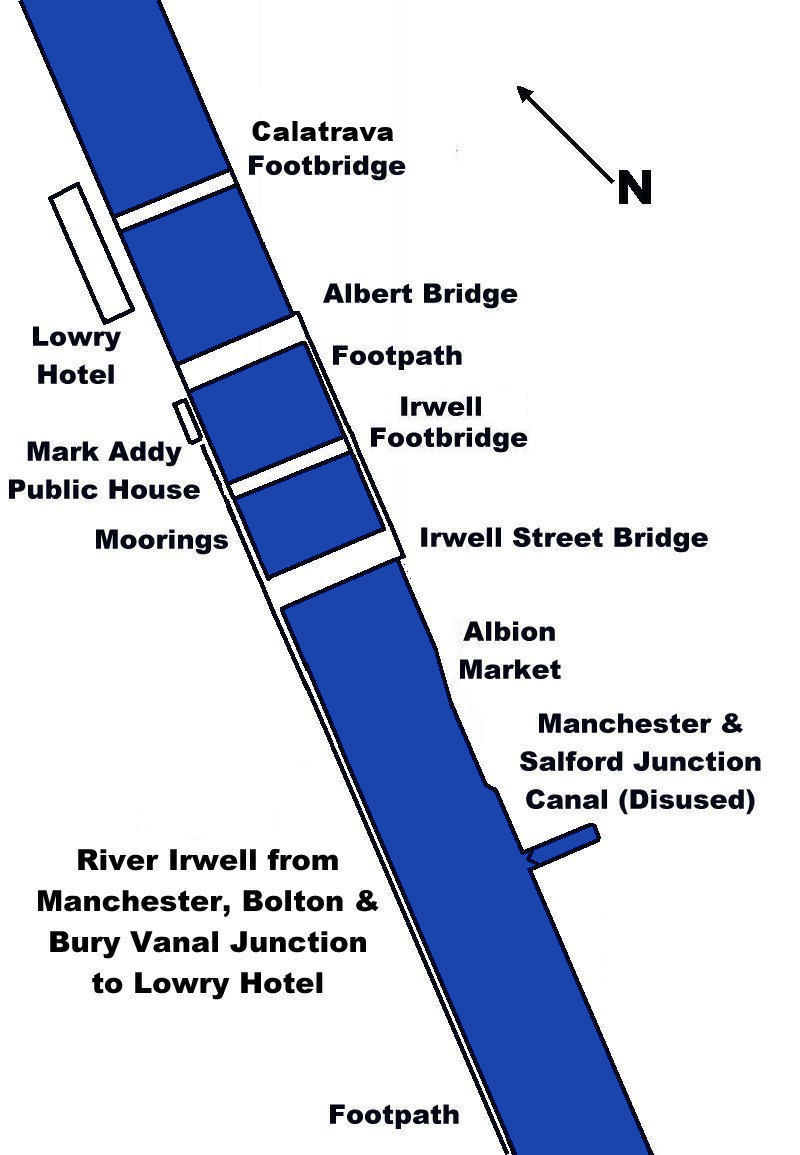

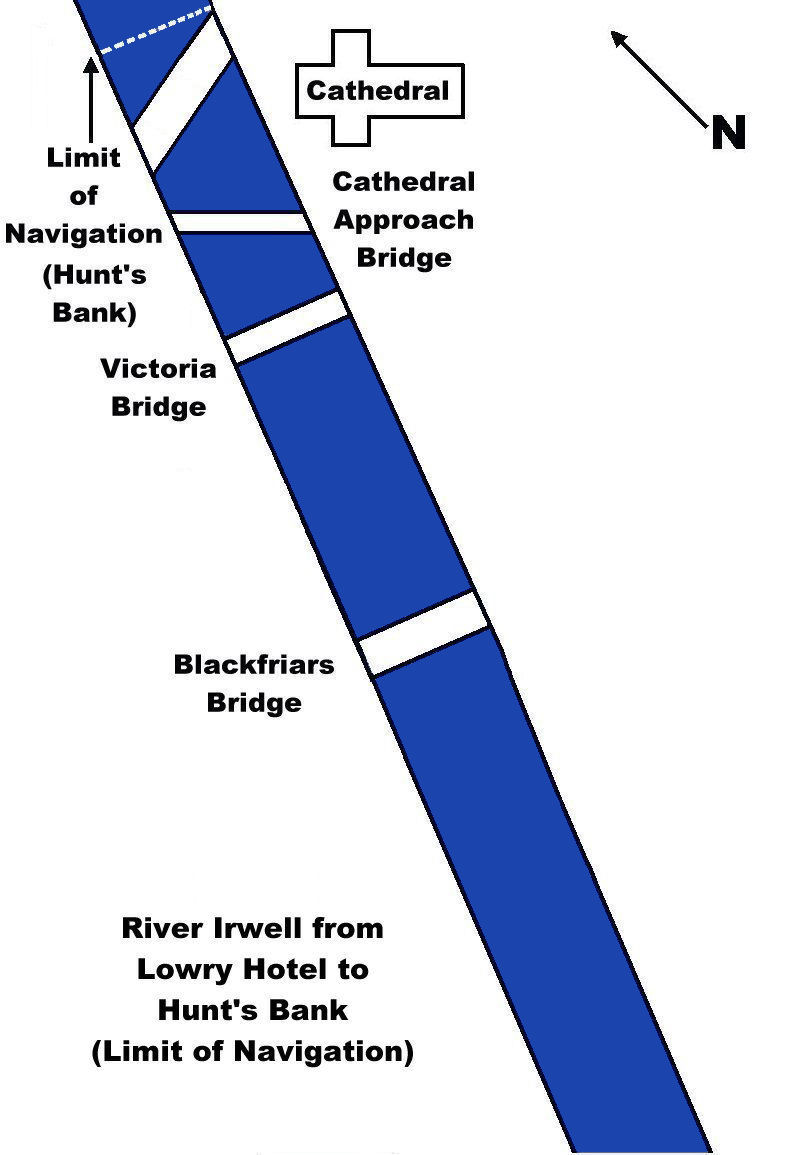

up-dating the original maps plus the inclusion of maps and photographs of the

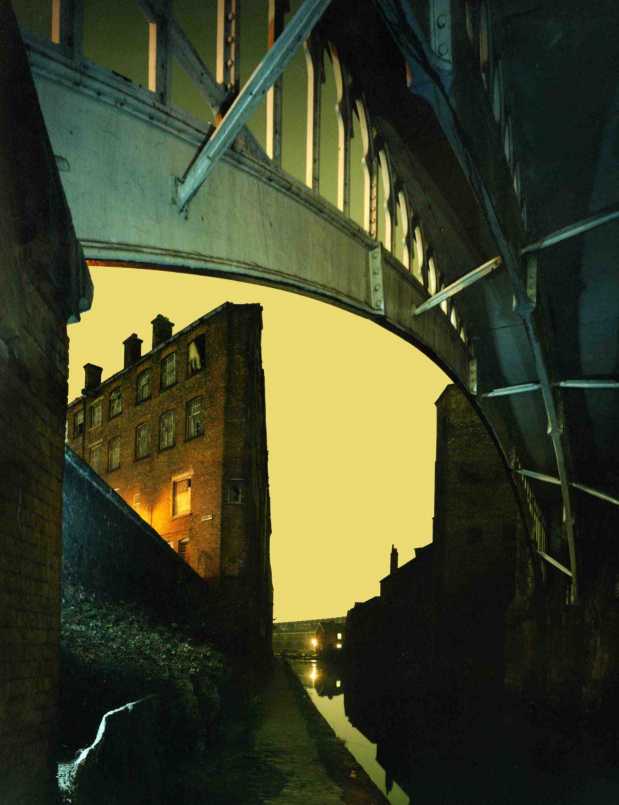

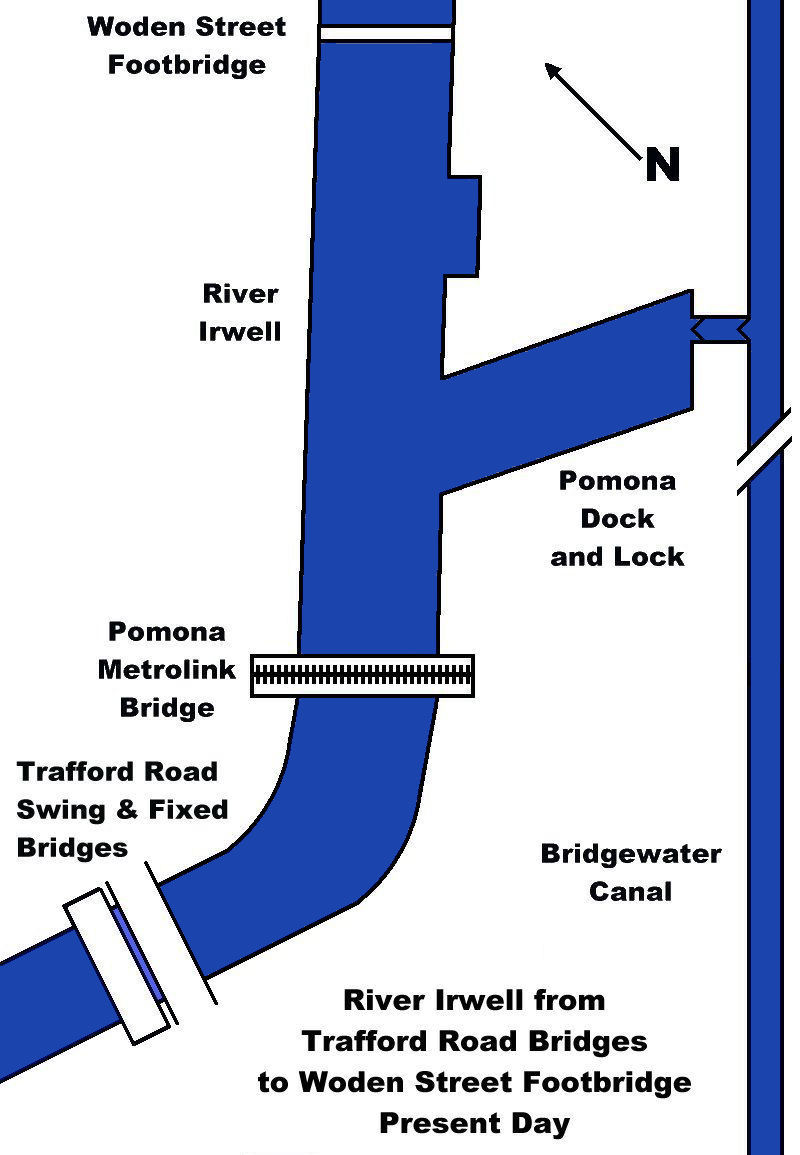

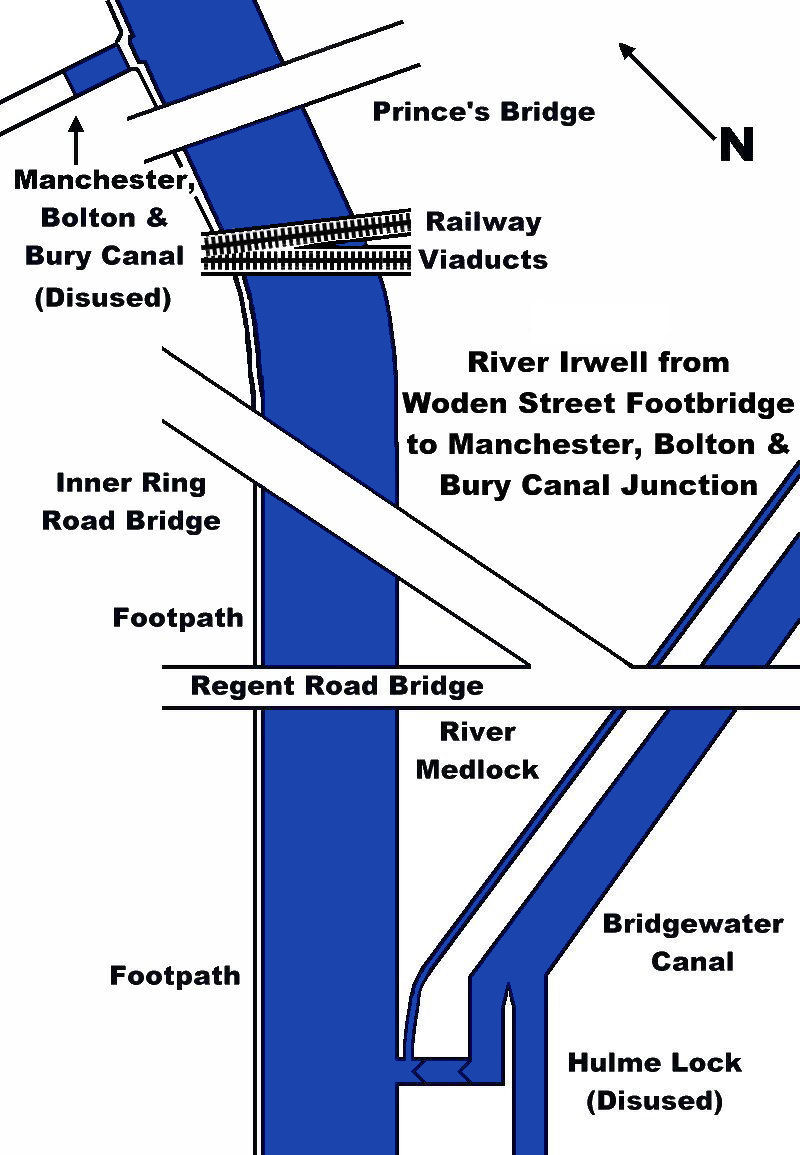

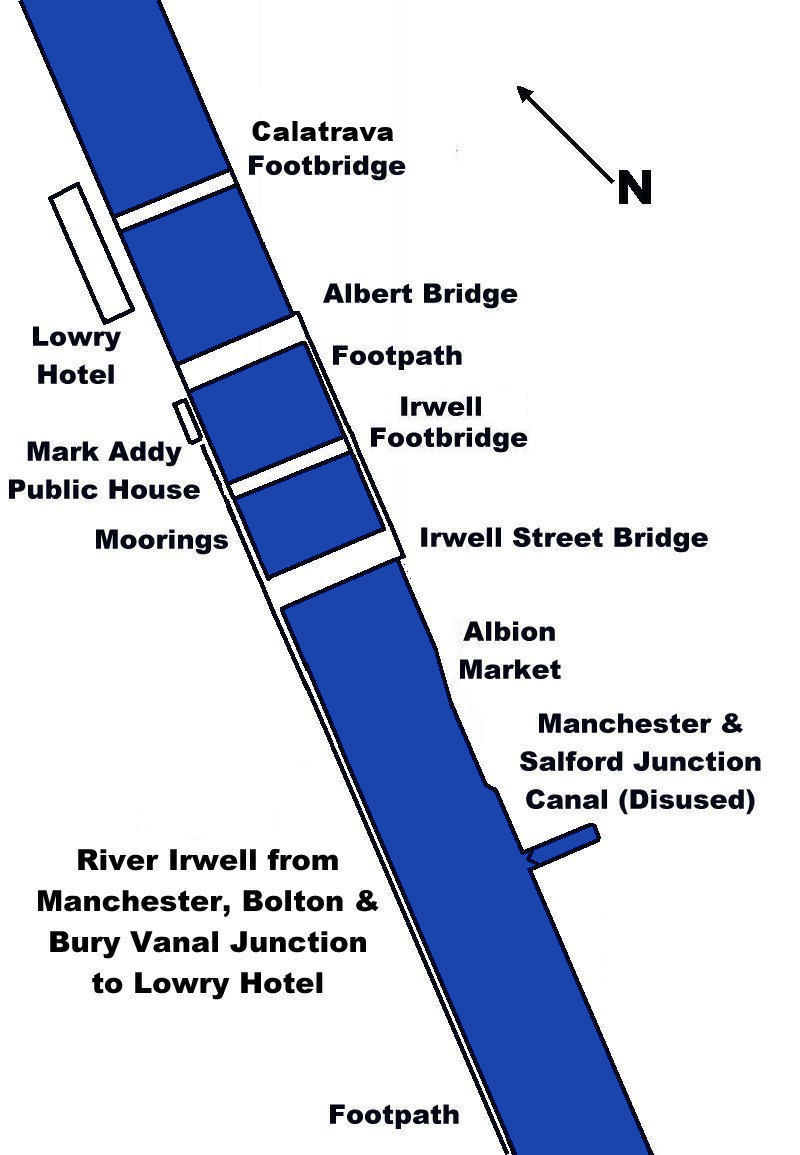

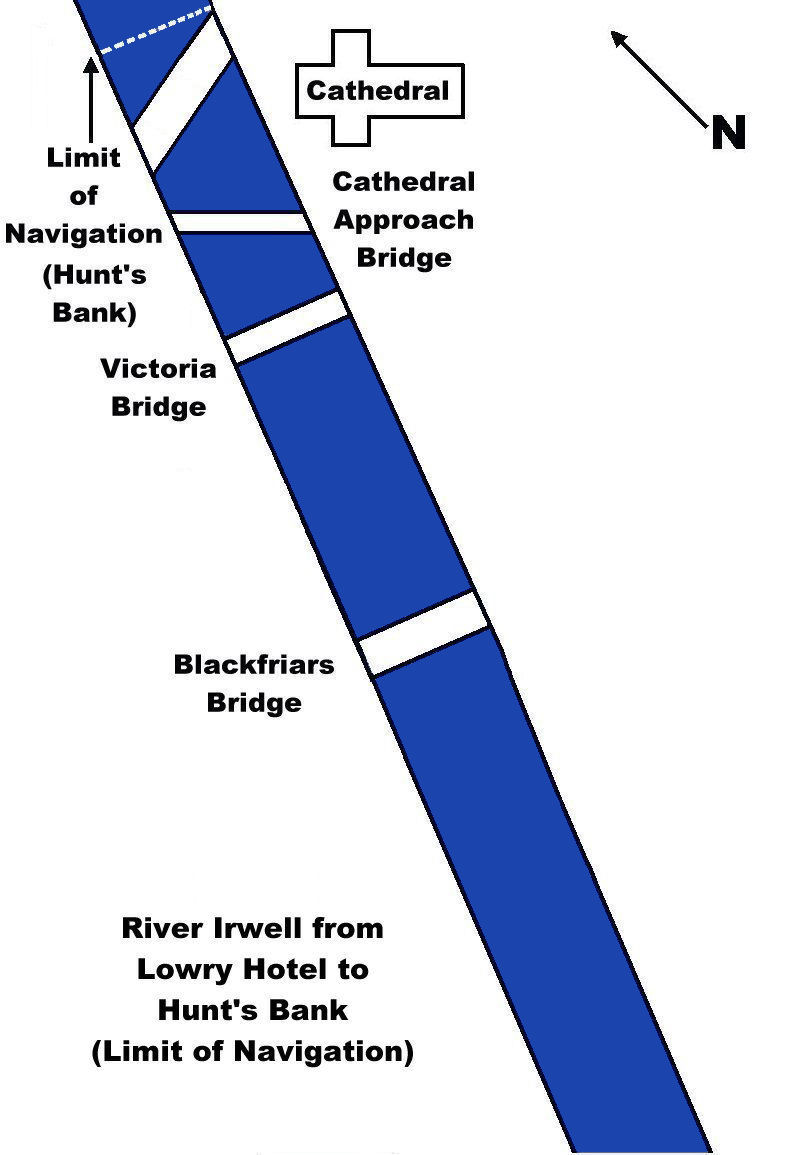

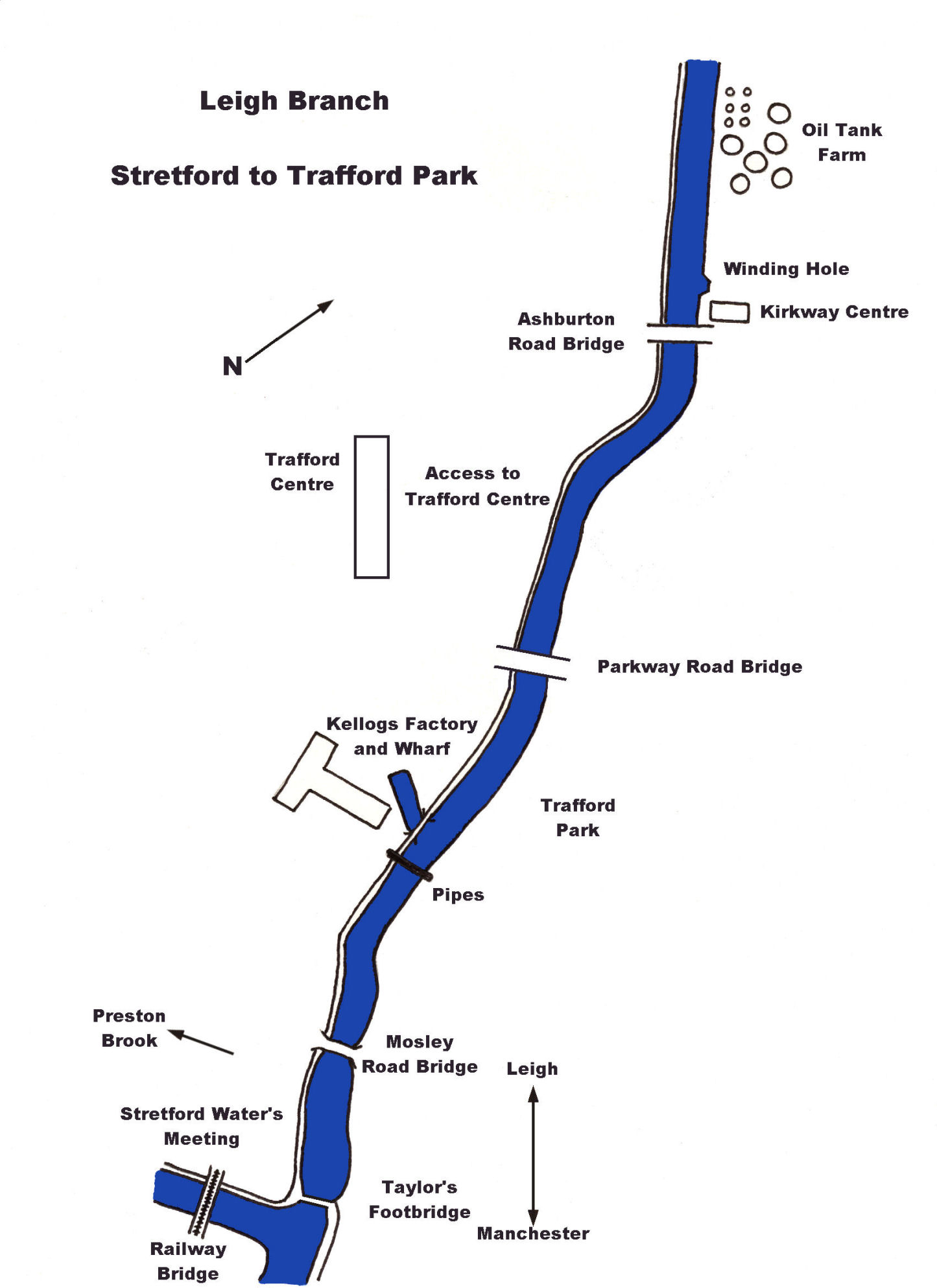

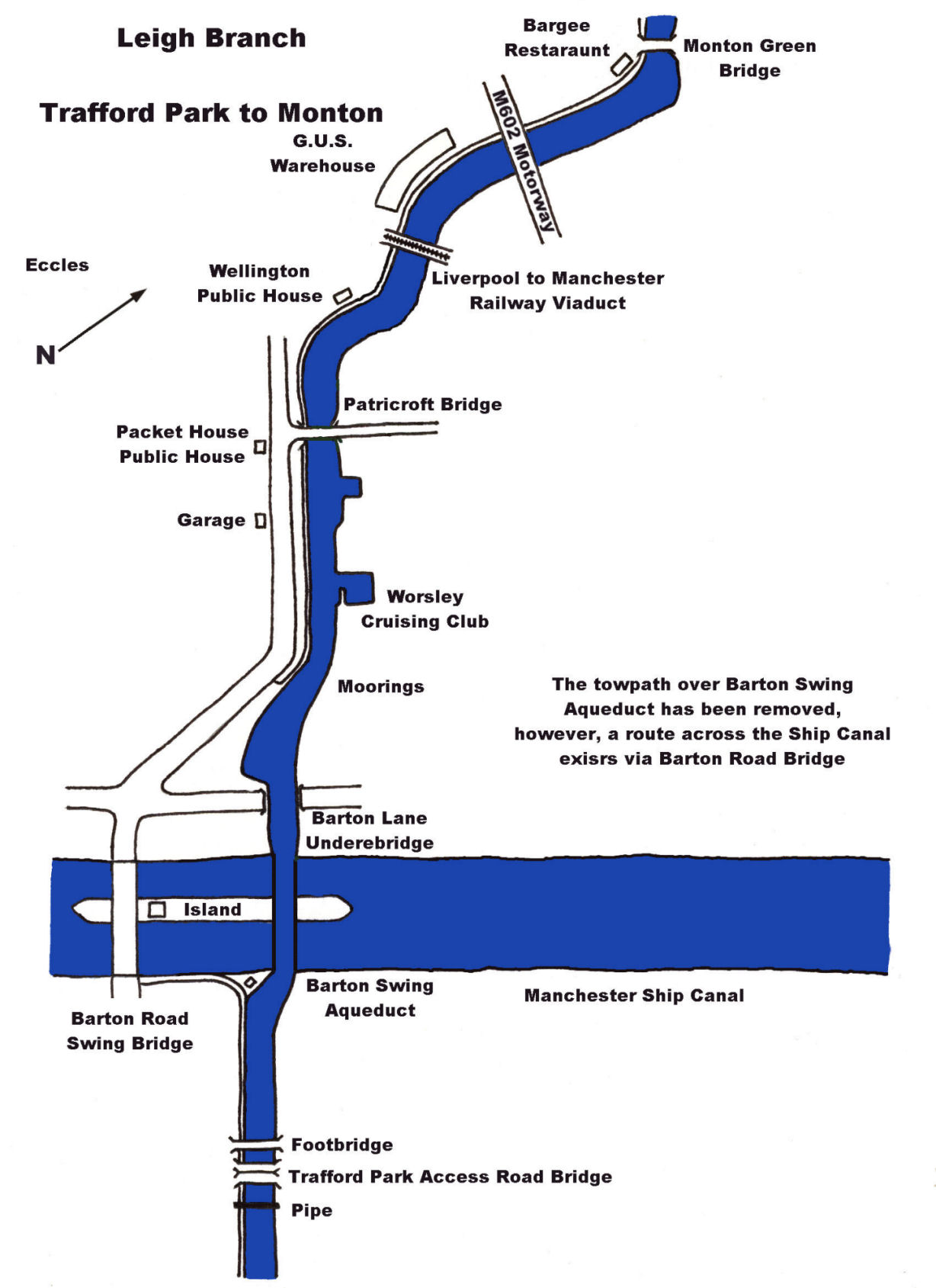

Runcorn Locks Restoration Project, the River Irwell and

Upper Reaches of the Manchester Ship Canal. I have included them due to the

on-going restoration of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal which is

accessed via the River Irwell. Accordingly, the Bridgewater Canal Company

Limited have relaxed regulations relating to the passage of Pomona Lock, navigation of the River Irwell

and the Upper Reaches of the Manchester Ship Canal (Salford Quays from

Lowry Footbridge going upstream). With having

the book in an electronic format (plus not

working to a publishing dead-line) also gives me the opportunity to make

the smaller corrections and modifications to the manuscript;

keeping it up-to-date, that would

previously require completely re-typesetting the book. With not being

limited to the number of photographs also allows me to reinstate some of the

previously deleted images.

The

History of the Bridgewater Canal

The first

inland navigations in

England

can be attributed to the Romans. They constructed navigable cuts known as

“Fosses” or “Dykes” in some of our rivers to bypass navigational hazards.

Three of the better known of these cuts are the Caer Dyke, the Fosse Dyke

and the Itchen Dyke. The

Carr (or Caer) Dyke ran from the River Witham at

Lincoln

to Peterborough

and the Fosse Dyke also ran from the Witham at Lincoln but connected the town with the River

Trent. The Itchen Dyke ran from Winchester to the sea. No doubt, these

artificial waterways were monumental in the development of the

Lincoln area.

Another fosse that is often overlooked in the history of our Inland

Waterways was built in the Castlefield area of Manchester to connect the

Rivers Irwell and Irk. This particular fosse was built around A.D. 84 and in

building this waterway, the Romans laid the foundation stone for a series of

waterways, the development of which, was to have a profound effect on

transport in this country at the start of the Industrial Revolution and

beyond. Unfortunately, no remains of the Castlefield Fosse can be found.

Remains of the Roman Fort at Castlefield in Manchester

Over

the successive centuries there have been a few other attempts to produce

workable navigations. The erroneously named

Exeter

Ship Canal

(which could only accommodate barges)

was constructed in

1566 by John Trew ran alongside the

River Exe in Devon. It was originally constructed to by-pass a section of the River

Exe notorious for shoals and scours, connecting Exeter to the sea. This navigation featured

the first pound locks (as against flash locks) in England. Pound locks are often

attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci but there have been locks of this type in

Holland since the

Fourteenth Century, well before Da Vinci’s birth. One of the

busiest natural waterways in the country was the River Severn. It is only

natural that it should figure somewhere in the development of the Inland

Waterways system. Two notable navigations connected to the

Severn

are the Dick Brook and the River Stour Navigation, both built by Andrew

Yarrington.

The Exeter Ship Canal in Devon

Scroop Egerton, the first Duke of Bridgewater, owned mine

workings at Worsley near Manchester,

and required a reliable means of transporting his coal not dependent on

pack horses and carts via the notoriously unreliable roads. In 1737, the Duke

commissioned Thomas Steers to investigate the practicality of making the mine’s

drainage soughs and the Worsley Brook navigable as far as the River Irwell.

Steers had considerable experience in civil engineering. He was responsible for

Liverpool’s

first dock and a survey to make the River Irwell navigable to

Manchester.

The Duke’s plan was dropped when improvements were made to the nearby River

Douglas and he died in 1745.

The Worsley Brook

The history of inland waterways navigation in this area is

complex and many schemes overlapped each other both in the historical and

geographical context. For instance, the plans to make the River Douglas

navigable caused the plans for the

Bridgewater

Canal

to be

postponed

but figured in the development of the

Leeds and

Liverpool

Canal

many years later. The River Irwell and subsequently the

Mersey and Irwell

Navigation were, one hundred and fifty years later, to be absorbed into one of

the most ambitious canal projects in England…

the Manchester

Ship Canal.

Mode Wheel

Lock on the Mersey and Irwell Navigation

1754 saw a survey to make another brook, the Sankey Brook,

navigable from Saint Helens

to the River Mersey. A local engineer, Henry Berry, carried out the survey. Work

soon started and by 1757, the

Saint Helens (or

Sankey) canal was partly open. Whilst

being called canals, all of these early works utilised an existing watercourse,

whether it be a brook, stream or river and, as such, are not canals in the

truest sense of the word but “navigations” or to use the French description…

“collaterals”. The general consensus of opinion in inland waterway circles is

that the first canal built was the

Saint Helens Canal.

This is not strictly true and open to conjecture. The definition of a canal is

of a waterway constructed independent to any existing watercourses except for

the water supply. As the St Helens

Canal

is mostly the canalised Sankey Brook, it is classed as a navigation and cannot

be called a canal in the truest sense of the word. The first true canal in Britain built

independent of a watercourse was the

Bridgewater

Canal or, as it is more

affectionately known… “The Duke’s Cut”.

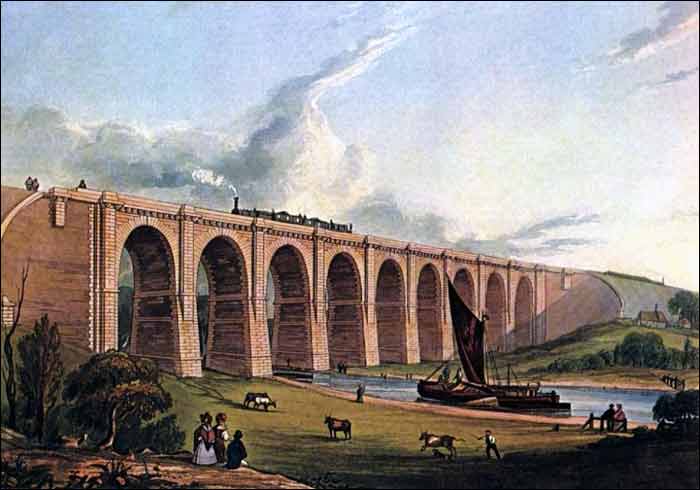

The St Helens Canal - the Sankey Viaduct

Francis Egerton was the sixth son of Scroop and became the

Third Duke of Bridgewater at the age of eight when his father died. He was

sickly child and suffered an unhappy childhood, being brought up by his mother

and stepfather who showed little interest in the young Francis, and punctuated

by episodes of tuberculosis. He was educated at Eaton until the age of sixteen

when Robert Wood was appointed the young Duke’s tutor. Wood agreed to take the

young Duke on a “Grand Tour” of

Europe where he

would be exposed to the sights and different cultures of a world outside that of

England.

Francis showed an interest in the transportation system of France and visited

the Canal du Languedoc (later known as the Canal du Midi) which, with the Canal

du Lateral connects the Atlantic Ocean at Bordeaux with Sète on the shores of

the Mediterranean.

Francis Egerton... the Third Duke of Bridgewater, in later years

The Canal du Midi at Homps as Francis Egerton

may have seen it

Once the Grand Tour was over, the young Duke returned to

England

and was absorbed into

London’s

social life. It was here that he met the widowed Lady Elizabeth Hamilton (one of

the Gunning sisters, well known in

London’s

social circles) with whom he had a love affair and was to become engaged to. The

Duke dissolved the engagement due to a scandal in the Gunning family concerning

Elizabeth’s

sister, a decision that caused him much heartache.

Dismayed with London life he decided to dedicate his life

to commerce. In 1757 he left London

and headed for his mines at Worsley near

Manchester

where he took up residence in the family estate at Worsley Hall. The

relationship with his mother plus his affair with Lady Hamilton had scarred him

emotionally and he became a misogynist; hating women to such an extent that he

would not even allow female servants at the Hall.

Lady Elizabeth Hamilton (nee Gunning)

After settling in to his new life, he consulted with John

Gilbert, the mine’s agent and engineer to discuss problems associated with the

mines. It transpired that the two main problems were that of transportation of

the coal and mine drainage. At that time, the coal was carried by cart or

packhorse to the River Irwell where exorbitant charges were made to transport

the coal to

Manchester,

its main market.

Pack horses and carts transporting coal

Egerton had seen the success of the Grand

Languedoc

Canal

(Canal du Midi) and other Continental waterways on his Grand Tour of Europe and

was, no doubt, aware of the fledgling

Saint Helens

Canal

nearby. Together, he and Gilbert resurrected Scroop Egerton’s idea for a canal,

expanded upon it to incorporate an elaborate drainage system for the mines and

started to survey the route. The proposed canal would not only solve the

transportation problem and alleviate that of the mine’s drainage, it would bring

down the price of Worsley coal in Manchester, thus, making it more competitive

and an affordable commodity for the less affluent members of society. The following year, Egerton was introduced to a millwright

called James Brindley by John Gilbert. Brindley travelled to Worsley and stayed

as the Duke’s guest for six days discussing mine drainage and the proposed

canal. Five years earlier, Brindley had been involved in extensive mine drainage

works at the not too distant Wet Earth Colliery near

Clifton

(adjacent to where the disused

Manchester,

Bolton

and Bury

Canal

is today). No doubt, the success of this scheme helped to make up the Duke’s

mind when he decided to engage Brindley to make complete the survey for the

canal already started by John Gilbert.

An engraving of James Brindley

Brindley soon completed the survey and in 1759, an Act of

Parliament was passed enabling the canal to be built. The proposed route was to

run from the mines at Worsley to the River Irwell at Salford Quay with a branch

to Hollins Ferry also on the Irwell, 9.6 km (6 miles) below

Barton

Bridge.

On 1st

July 1759, work on the canal commenced,

but in November of that year the Salford Quay terminus was dropped in favour of

Dolefield and an additional Act of Parliament obtained. There is an interesting offshoot to the early history of

the

Bridgewater

Canal.

Francis Egerton’s brother-in-law was Lord Gower, who owned coalmines and

limestone quarries in the rapidly expanding industrial area of

Shropshire. His

land agent was John Gilbert’s brother… Thomas Gilbert. It is obvious that

communication had taken place between the two families that lead to the

foundation of the canal system in

Shropshire which

lead to the area being christened “The Cradle of the Industrial Revolution”. Around this time, another canal was being proposed. This

was the Grand Trunk or, as it was later to be known, the

Trent

and Mersey

Canal.

This canal was the brainchild of Josiah Wedgwood the potter and would bring clay

to his potteries, transport the finished pottery in addition to serving the

Cheshire

salt industry. It is interesting to note that two of the main promoters of the

canal were none other than Lord Gower and Thomas Gilbert. Wedgwood had also

secured the services of James Brindley to survey and build the canal. Brindley

saw the Grand Trunk as the foundation stone for a system of canals connecting

the Rivers Trent, Mersey, Severn and Thames, with other canals branching off to

serve various towns and cities. Hence the name… “Grand Trunk”, like a tree with

branches spreading out to various parts of the country.

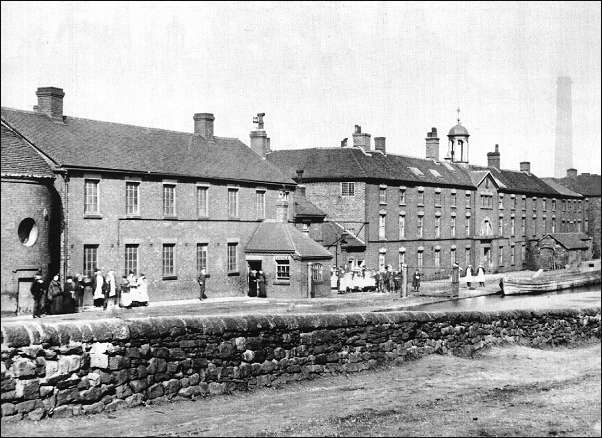

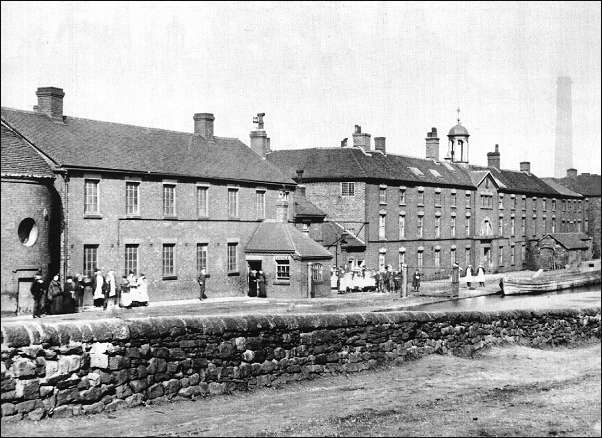

Wedgewood's Etruria Works at Stoke on Trent

The mines at Worsley were constantly being expanded

downwards and outwards in order to reach the seams of coal that ran throughout

the area. Trips were even arranged for the adventurous to view the workings

first hand for a nominal fee. Meanwhile, construction on the Bridgewater

Canal

had been progressing from both ends. Several engineering hurdles had been

crossed and the canal had reached a major obstacle, the River Irwell. Initially,

a flight of locks were planned to lower the canal to the Irwell with another

flight to raise it up on the other side. This would have used too much of the

canal’s water resources so Brindley planned to bridge the river using a masonry

aqueduct (the stone being waste, obtained from the Worsley Mines) lined with

puddled clay (wet clay kneaded like dough) to make it waterproof.

When the Act for the aqueduct was proposed, MPs reading the

proposal called Brindley into their Chambers at the House of Commons in order

for him to demonstrate how he expected to make the bridge waterproof. Brindley

was semi-literate and often resorted to drawing diagrams with whatever was at

hand. In addition to drawing on the polished floor of the Parliamentary Chambers

he demonstrated how the aqueduct would work with the aid of a large cheese,

which he carved to represent the aqueduct, filling it with water when the model

was completed.

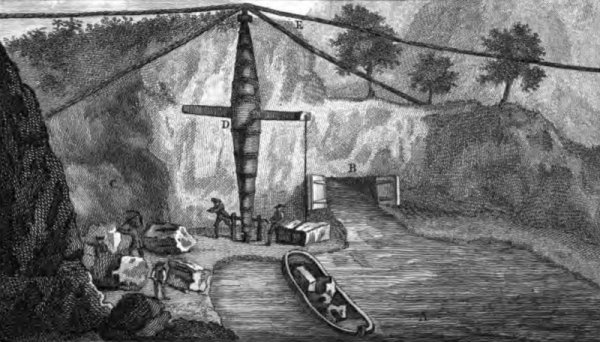

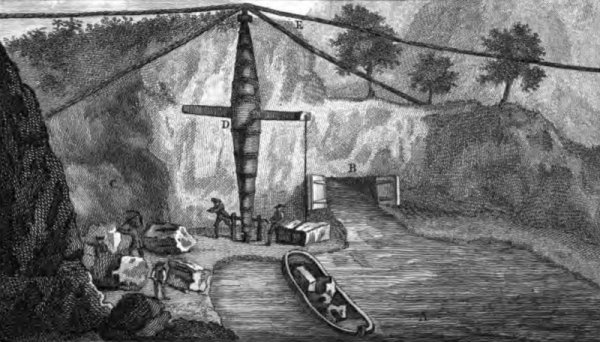

Worsley Delph circa 1770

Brindley

also demonstrated the theory of clay puddling by bringing buckets of water and

wet clay into the chambers. He then gave a practical demonstration of how clay

could be made waterproof by puddling and then applied to the masonry to make it,

in turn, waterproof. Needless to say,

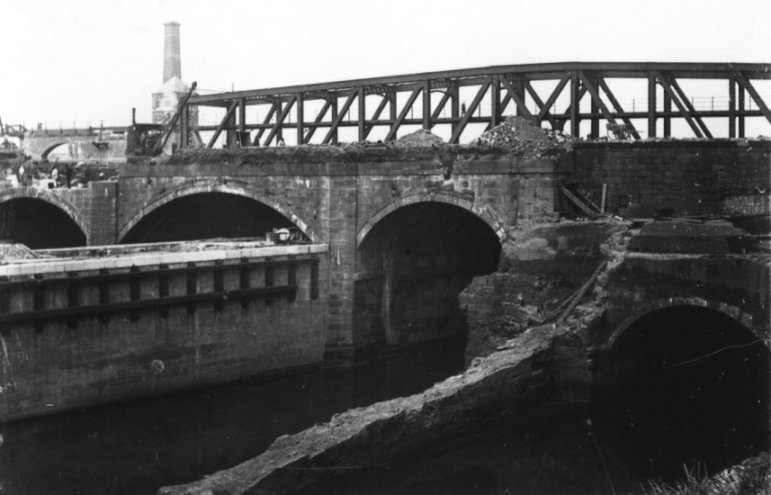

the Act was passed and on 17th

July 1761, water was admitted to the

completed Barton Aqueduct, which opened the

Bridgewater

Canal

from Worsley to Stretford

on the outskirts of Manchester. Barton

Aqueduct was a three arched masonry structure, 183 mtrs (600 ft) long, 11 mtrs

(36 ft) wide and 12 mtrs (39 ft) high. Scepticism was rife prior to it’s

opening. It was given the nickname “Castle in the Air” and many people thought

that it would surely collapse when water was admitted. Needless to say, Brindley

proved the sceptics wrong although there was a problem when one of the arches

started to bulge. This necessitated the drainage of the aqueduct after the

opening ceremonies but was soon rectified and the canal was open to through

traffic. When posed with a problem, Brindley would often retire to his bed and

ponder the best course of action. On this particular occasion, when he rose from

his deliberations, John Gilbert had already solved it for him, completed the

remedial work, and refilled the aqueduct. Brindley’s comments on this action are

not documented.

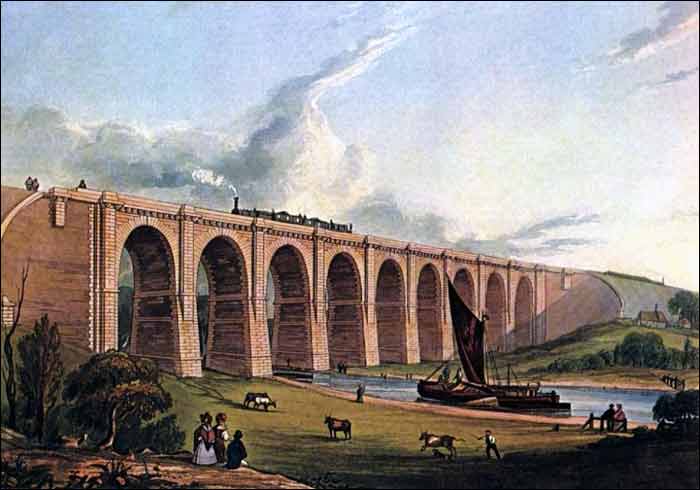

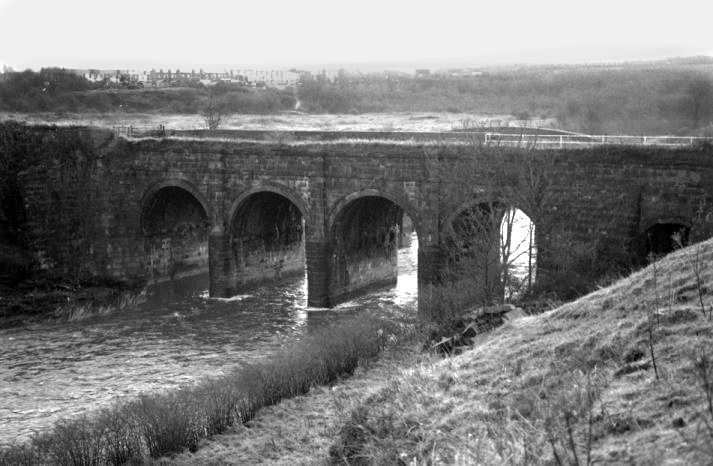

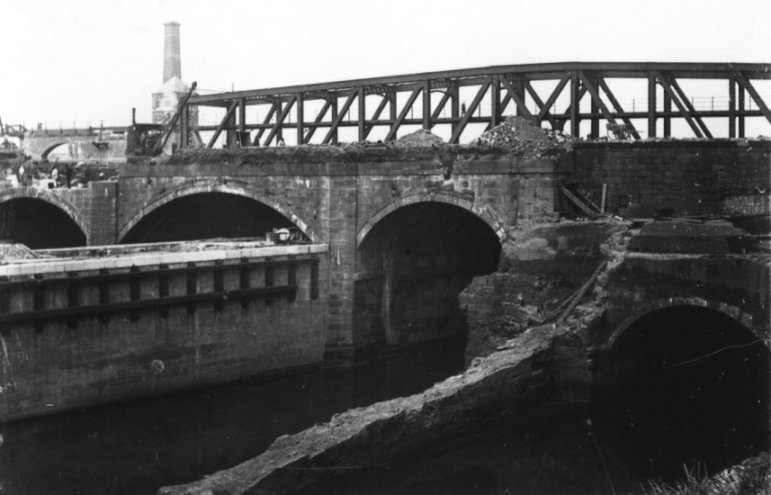

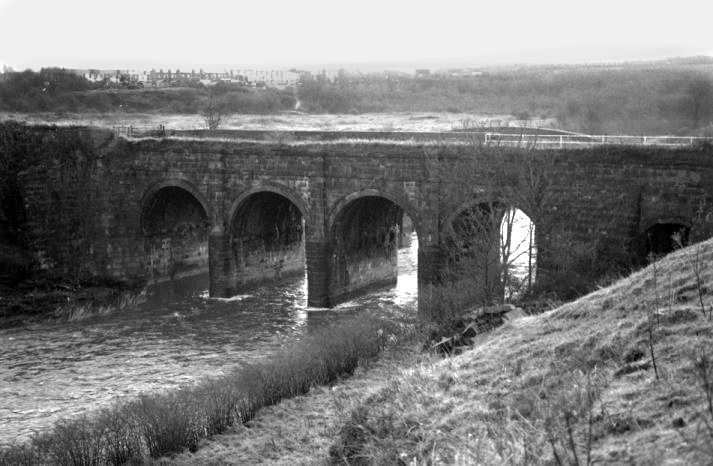

Brindley's original Barton Aqueduct over the River Irwell

The building of the remainder of the proposed route was

progressing well and in 1763 the terminus was changed yet again making

Castlefield, near Deansgate, the eventual terminus. Also in this year, a

connection at Cornbrook was made with the

Mersey and Irwell

Navigation. This connection was known as “The Gut”, but could only be used when

there was sufficient water in the river to overcome the silting and low river

water levels. Castlefield was reached in August 1765 and, in doing so, marked

the completion of the first canal in England

to be constructed independent of a watercourse.

During the period of construction (and afterwards) the Duke

had amassed a considerable debt. He borrowed money from many people to finance

the building of the canal. When not in residence at Worsley, he was constantly

visiting possible contributors in an effort to raise extra funding. It was to be

many years before his financial labours bore fruit, the debts were satisfied and

the canal returned a profit.

Meanwhile, Brindley had not been idle. In addition to his

work on the

Trent

and Mersey

section of his Grand Trunk scheme, he had started work on the Staffordshire and

Worcestershire

Canal,

which would connect the

Trent

and

Mersey Canal

at Great Heywood Junction near Cannock Chase to the River Severn at Stourport.

In September 1761, he started the survey on another venture for the Duke of

Bridgewater. This was a canal running from a junction with his existing canal at

Stretford

to join the River Mersey at Runcorn. This line of the canal would prevent the

Mersey

and Irwell Navigation’s monopoly in this area. The locks at Runcorn would also

provide a connection to the proposed Duke’s Dock at

Liverpool,

which was not to be completed until 1774. At

this time it was decided to abandon the branch at Hollins Ferry even though two

miles of it had already been cut from Worsley. March 1762 saw the Act of Parliament for the Runcorn Line

passed on which work started immediately. Another Act of Parliament, which

concerned the

Bridgewater

Canal

directly, was the Trent and Mersey Canal Act of 1766. In addition to allowing

construction of the canal, it also contained a change to the

Bridgewater’s

original line, allowing the two canals to link up at Preston Brook near Runcorn.

Waters Meeting at Preston Brook looking towards Runcorn

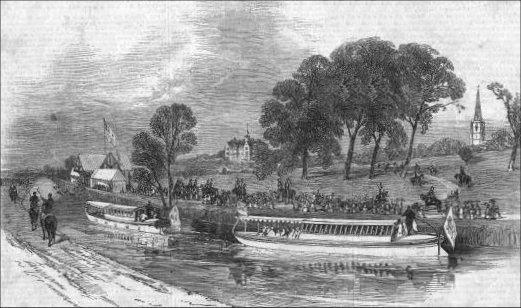

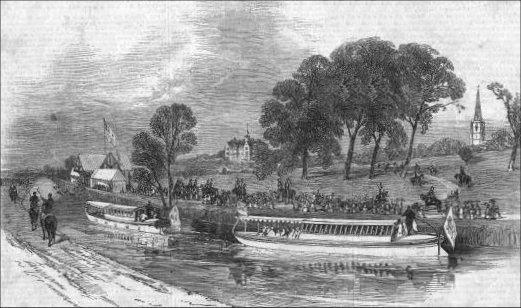

In the following year, 1767, passenger traffic commenced

on the

Bridgewater

Canal

in specially constructed “Packet” boats. The boats were of lighter construction

than conventional craft to facilitate greater speed and even possessed a sharp

knife on the bows to cut the towropes of any other craft that dared to get in

their way. This service proved to be very popular and, as the canal was extended

in length, so was the service.

After

various challenges such as the aqueduct over the Infant River Mersey and the

crossing of the marshy Sale Moor, Lymm was reached in 1768. However, in the

following year, construction at the Runcorn end came to an abrupt standstill

when Sir Richard Brook, a local landowner, objected to the canal’s presence on

his estate at Norton Priory. This held up construction for a few years.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the canal, Stockton Heath had been reached. When

overseeing construction of the Runcorn end of the canal, the Duke and Brindley

both stayed at the imposing “Bridgewater House”. This was a residence that the

Duke had built at Runcorn, situated adjacent to the flight of locks connecting

the canal to the River Mersey.

Bridgewater House in Runcorn adjacent to the Manchester Ship Canal

Brindley was a diabetic and his health was suffering. He

was continually commuting between his other canal projects; the Staffordshire

and Worcestershire,

Oxford,

Coventry,

Chester,

Calder and Hebble, and many more. His mode of transport was by horseback,

spending nights at inns and travelling in all weathers. He caught a chill, which

added to his diabetes and died on

27th

September 1772 at the age of 56.

James Brindley's Statue at Etruria Junction, Stoke on Trent

1772 also saw the completion of the flight of ten locks

leading down to the River Mersey at Runcorn. They could not be used though,

until the disagreement with Sir Richard Brook had been resolved. This

disagreement lasted until 1775 when Parliament intervened and a settlement was

reached. The impact on the canal of this settlement still remains with us to

this day. This is the deviation of the canal’s route in the shape of an “s” bend

around Sir Richard Brook’s land and the changing sides of the towpath between

Old

Astmoor

Bridge

and

Norton Bridge.

The only other place on the Bridgewater

Canal

where the towpath changes sides is in

Manchester

between Old Trafford and Castlefield.

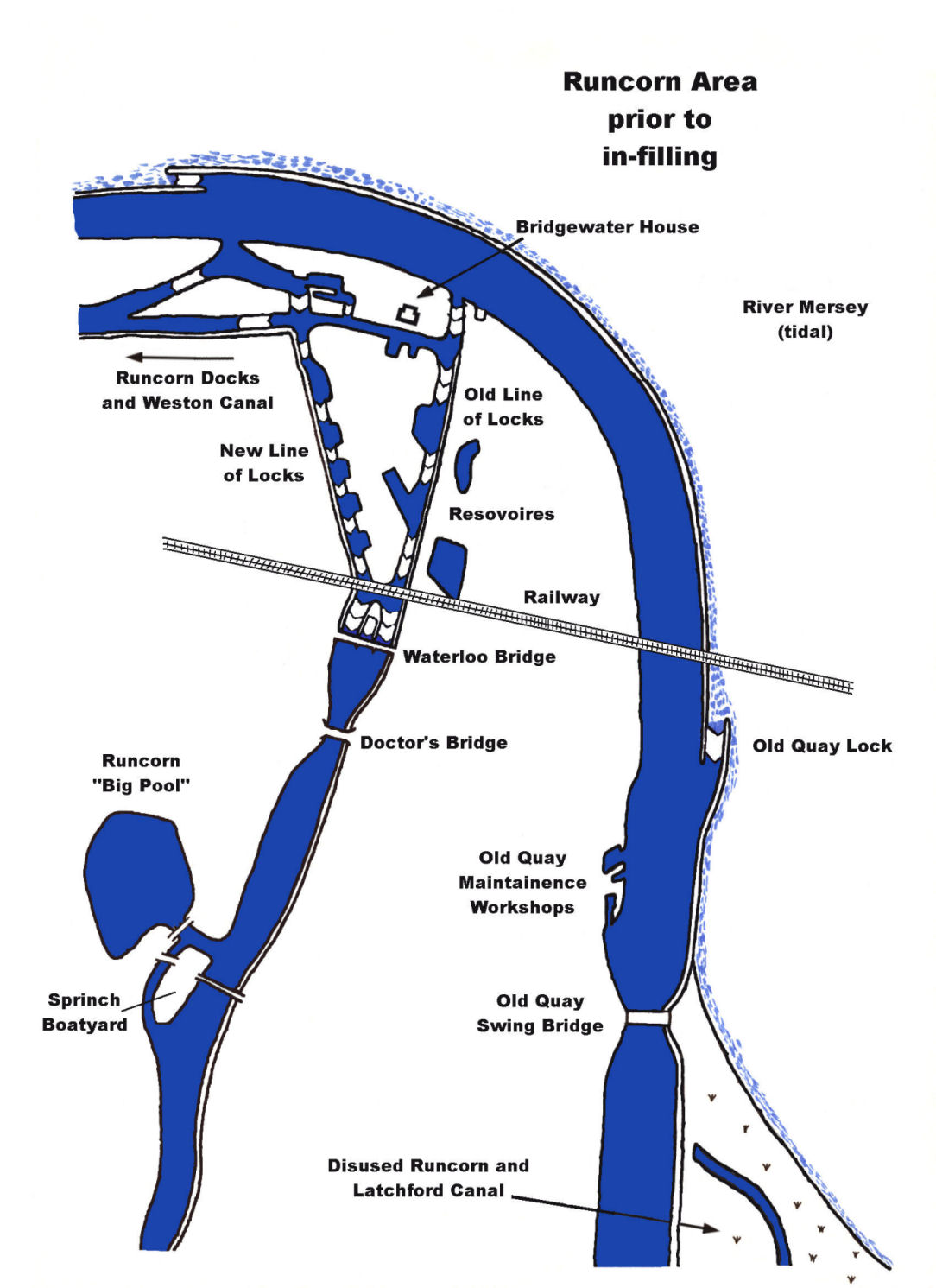

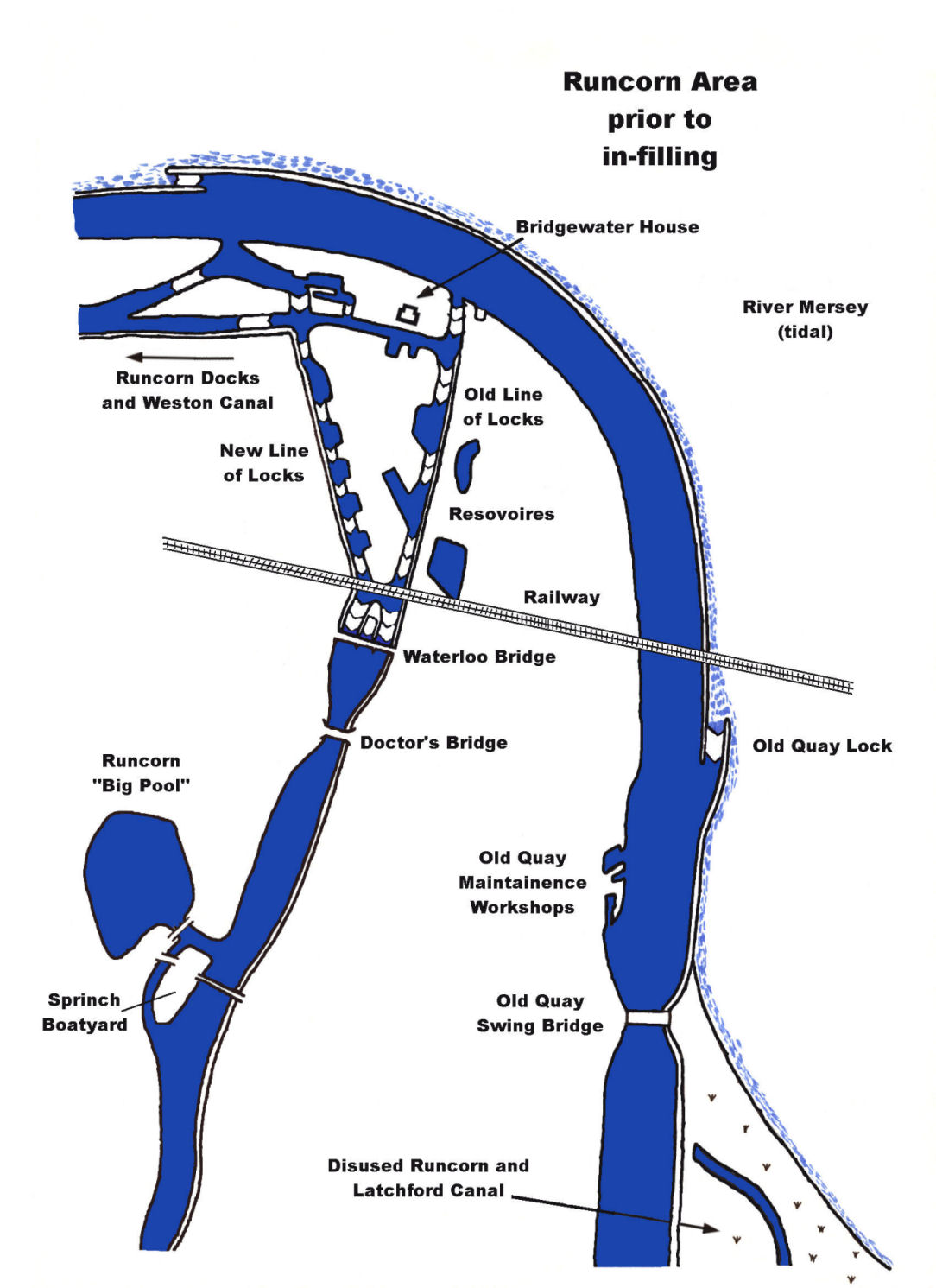

Runcorn New Line of Locks prior to infilling

Another memorable happening in 1772 was the linking of the

Bridgewater with the

Trent

and

Mersey Canal.

The actual place where the two canals meet is 10 mtrs (11 yds) inside Preston

Brook Tunnel. The spot is marked by a

Trent

and Mersey

Canal

milepost on the horse path (as the tunnel does not possess a towpath, boats were

originally “legged” through until a steam tug service was introduced) that goes

over the top of the tunnel.

The first Trent and Mersey Canal milepost on top of Preston Brook Tunnel

Today, the entire length of the tunnel comes under

the jurisdiction of British Waterways, the

Bridgewater

Canal

commencing at the stop boards at the northern portal.

The northern portal of Preston Brook Tunnel in the 1930s

The northern portal of Preston Brook Tunnel as it is today

In January 1776, the final mile through Norton Priory was

cut and the canal opened for through traffic on the 21st March of

that year. It was a pity that James Brindley was not alive to see his canal

completed. The latter part of the Eighteenth Century saw Acts of

Parliament for two canals that would eventually link with the northern end of

the

Bridgewater

Canal.

They were the Leeds

and

Liverpool

Canal

in 1791 and the Rochdale

Canal

in 1794. It seems coincidental that two of the three cross-Pennine waterways

should be directly connected to the

Bridgewater

Canal,

and the third, the Huddersfield

Narrow

Canal,

connected via the Rochdale

and Ashton

Canals.

The Leeds

and Liverpool

Canal

was started in 1791 but it wasn’t until 1799 that part of the

Bridgewater’s

abandoned 1759 Hollins Ferry extension was extended to make an end-on junction

with the Leeds

and Liverpool

at Leigh. The part of the Hollins Ferry extension not used in the Leigh Branch

was to be used as a dump for dredgings, the remains of which, can still be seen

to this day just outside Worsley.

1795 must be mentioned for a much sadder reason, the death

of John Gilbert, agent and engineer for the Bridgewater Mines and Canal since

1757 and who, we must give some credit to, as one of the major inspirations

behind the

Bridgewater

Canal

along with Francis Egerton and James Brindley.

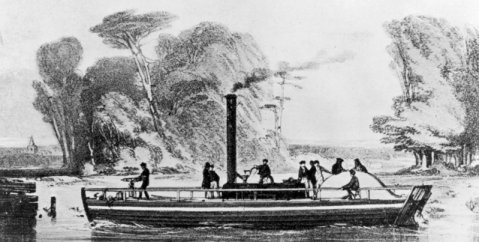

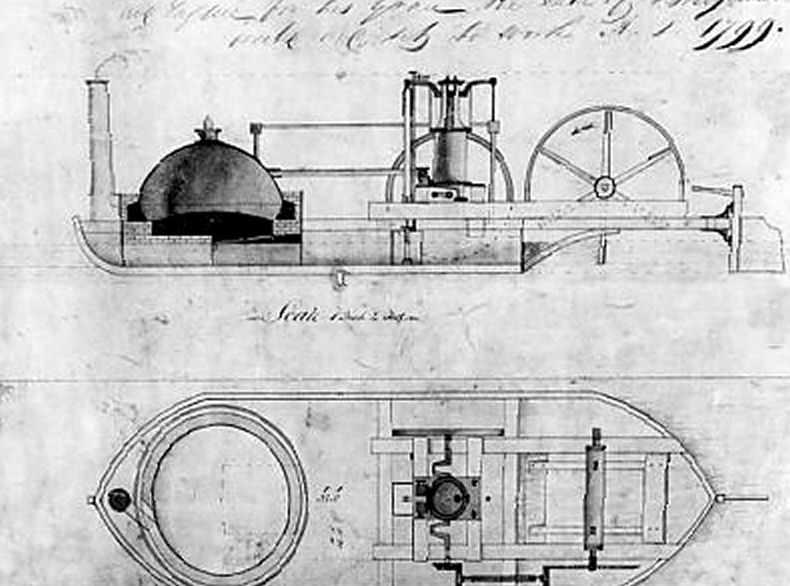

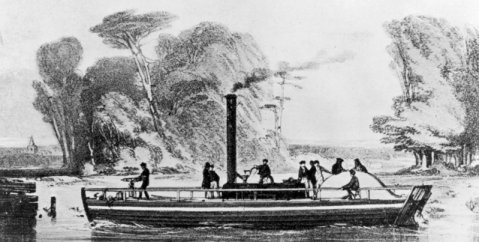

Right from the beginning of the canal’s history, horses had

been the prime motive force, but in 1796, an experimental steamboat was

commissioned by the Duke in an attempt to speed-up transport along the canal. By

1799 the craft was completed and sailed along the canal for the first time. The

boatmen along the canal looked upon the experimental tug with scorn, fearing

that this technological wonder would make their jobs redundant. They had little

to worry about as the stern-mounted paddle-wheel of the craft produced a large

wash that would have eroded the canal banks over a period of time. The craft was

withdrawn and broken up although it’s engine was used to power a water pump.

Even though not a success, it was to herald the change to steam propulsion that

took place over the next forty years.

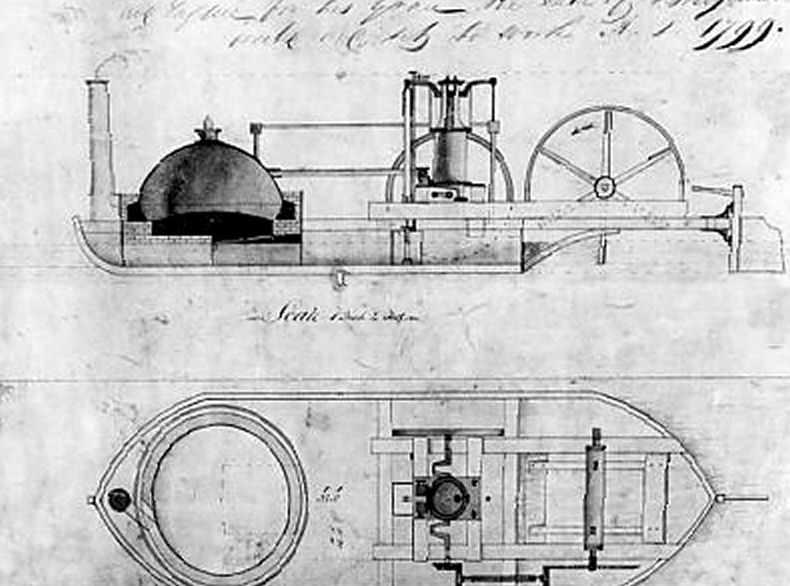

Illustration of the 1799 experimental steam boat used

on the Bridgewater Canal

By 1799, the Leigh Branch had reached Pennington and in

1800, the Rochdale

and Ashton

Canals

were opened to Castlefield. The

Rochdale,

however, was not completed and did not cross the

Pennines until

1804, the year after the Duke’s death.

The Third Duke was well liked and treated his workers with

kindness and (on the whole) respect. Even so, he was prone to eccentric

behaviour. He swore profusely, seldom washed and wore the same clothes day in

and day out. Concerned about his employees’ timekeeping, he arranged for the

clock in a turret of the works (later moved to Worsley Church) to strike

thirteen at one o’ clock signalling the end of lunch hour. On one occasion he

met a miner that was late for work and questioned him. The worker informed him

that his wife had given birth to twins during the night to which the Duke said…

“Ah well, we must accept what the Lord sends us”, to which the miner replied…

“Aye, but I notice he sends all the babies to our house and all the brass to

yours”! This reply may have pricked the Duke’s conscience as well as making him

laugh. He consequently gave the miner a guinea. As wages were paid monthly, he

arranged for employees wives to buy their groceries etc. on account at a local

shop, the bill being deducted from the workers’ salaries and the balance given

in cash, thus preventing the wages from being squandered in local hostelries.

The duke also formed a “sick club” for his workers to contribute to.

The Duke saw a demonstration of the “Charlotte Dundas”

experimental tug in 1801 and was so impressed that he ordered eight similar

craft to be built. Unfortunately the order was cancelled after the Duke’s death

in 1803 before any of the craft had been delivered.

The

experimental steam tug "Charlotte Dundas"

The Duke died on the eighth of March 1803.

His will of the laid down that the main beneficiary of the canal would be his

nephew… Earl George Gower, later to become the Duke of Sutherland. It also

stated that a Board of Trustees was to be formed to look after the interests of

the Duke’s estate. The Trustees were prominent national figures, many of which

had a vested financial interest in the well being of the Bridgewater Canal

overseen by George Gower. Later on, the Trustees of the Canal were to be Local

Councils, whose provinces the Canal passed through, and remained in place until

1903. On the death of George Gower in 1833, the profits from the Bridgewater

Estate went to his second son, Lord Francis Leveson-Gower, on the understanding

that he changed his name to Lord Francis Egerton.

In 1819, the

Leeds and

Liverpool Canal Act to build a branch that joined the

Bridgewater

Canal

was passed. The two canals were to meet at a “head-on” junction at Leigh, which

was completed two years later. The following year, 1822 saw a proposal for a

railway from

Manchester

to Liverpool.

Right from the outset, the Bridgewater

Canal

opposed it’s development, seeing the far-reaching repercussions it would have on

canals.

In an effort to make it’s route more comprehensive, two

extension plans were drawn up. The first in 1823 proposed an extension from

Sale

to Stockport

but was thwarted due to oppositions from the Ashton and

Peak

Forest

Canals.

The second plan, two years later, was far more ambitious. It was to be a canal,

possibly of ship canal dimensions, to link Runcorn on the

Mersey with

West Kirby

on the River Dee coast of the Wirral

Peninsula.

This plan was thrown out for many reasons, the major one being cost. It is

possible that the latter plan was to have been carried out by Thomas Telford

who, coincidentally, later carried out a survey to construct a ship canal from

Wallasey Pool to West Kirby

and so by-pass the River Mersey Estuary, which contained navigational hazards.

Telford is reported to have said about

Liverpool… “Look,

they’ve built the docks on the wrong side of the river”, due to Wallasey Pool,

the location of Wallasey and Birkenhead Docks, being a natural harbour. Had his

plan been successful, Liverpool would undoubtedly, not have had the successes

that it ultimately enjoyed.

Wallasey Pool

The Liverpool to Manchester Railway Company went to

Parliament with their Act in 1825, only to have it opposed by a joint objection

from the Bridgewater Canal and the Mersey and Irwell Navigation. However, the

respite was only a temporary one and the Act was successfully passed the

following year. Sensing that a battle was at hand, the Bridgewater

Canal

started a regime of expansion. A new line of locks at Runcorn was built next to

the existing ones in 1827. Along with this, new warehousing facilities at

Runcorn, Preston Brook and at many other locations including Castlefield were

built. The idea behind this regime was to speed up cargo handling and hopefully,

be more competitive when the Liverpool

to Manchester Railway was completed in 1830.

A more recent photograph of the MSC barge "Coronation" at the

Black Shed, Preston Brook

In 1833, amidst of the railway threat and expansion of the

canal’s cargo facilities, George Gower died. His son then (as previously

mentioned) changed his name to Lord Francis Egerton, First Earl of Ellesmere,

and took up residence at Worsley with his wife Harriet in 1837. Lord Egerton was

as concerned about the welfare of the workers as his namesake. His wife was also

concerned and encouraged her husband to abolish the use of children in the

mines.

Waterloo Bridge at Runcorn - the centre arch gave access to a dry dock

Over the

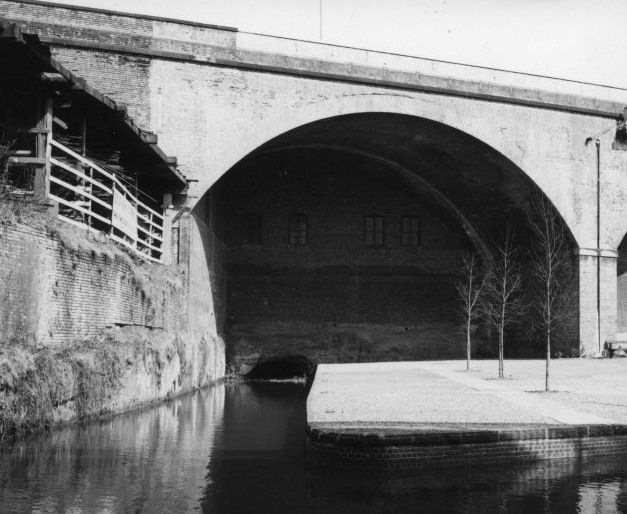

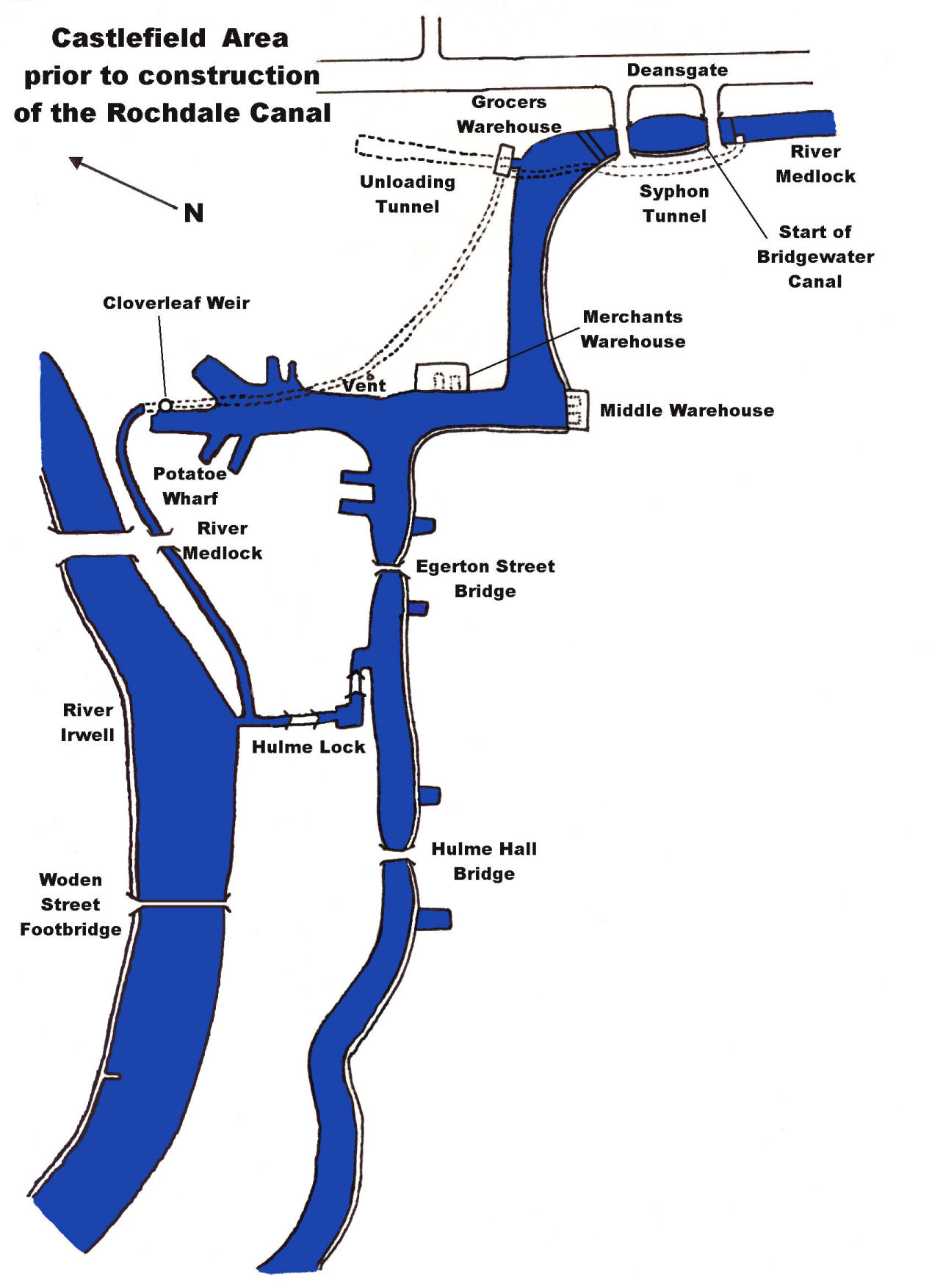

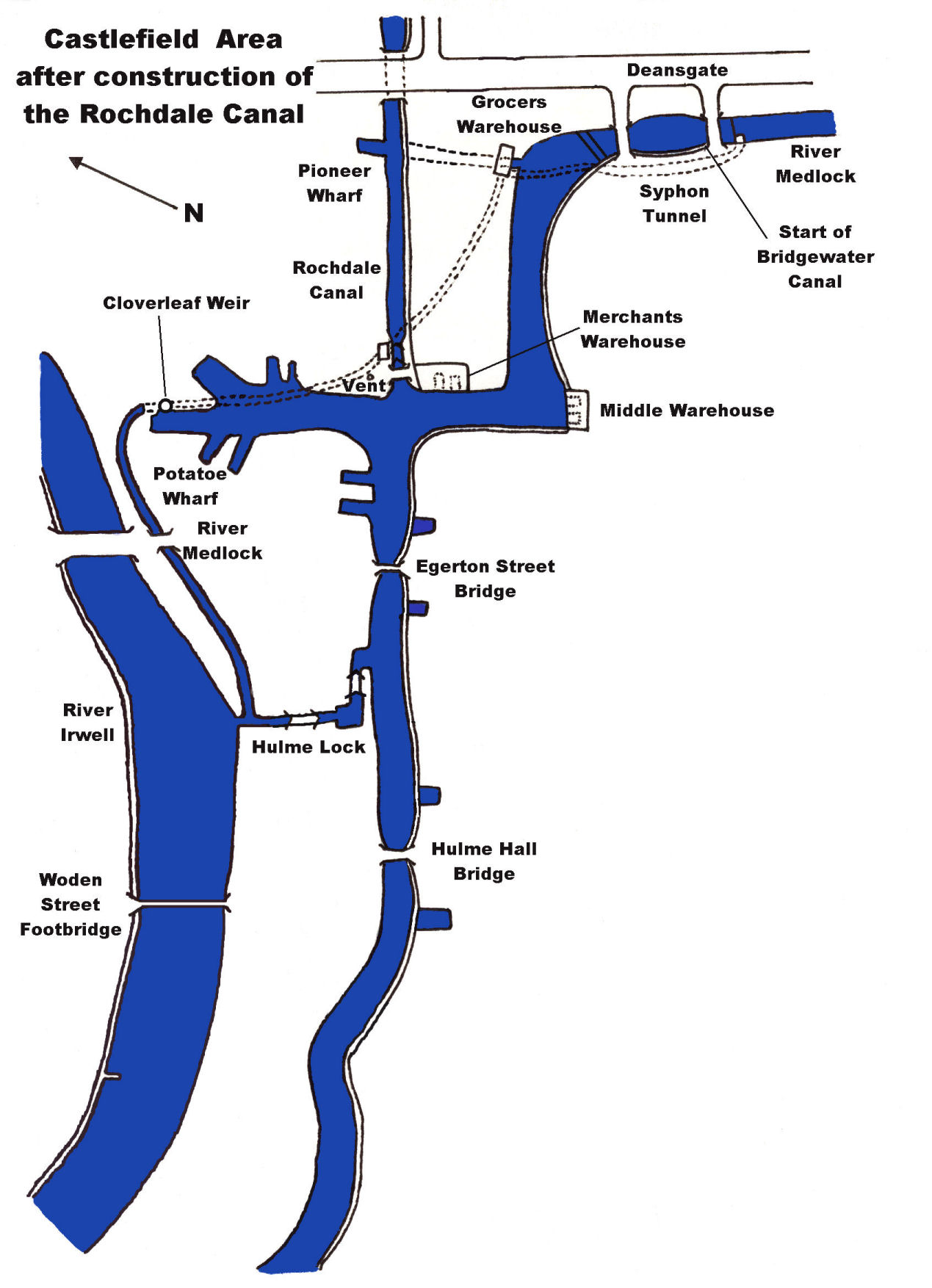

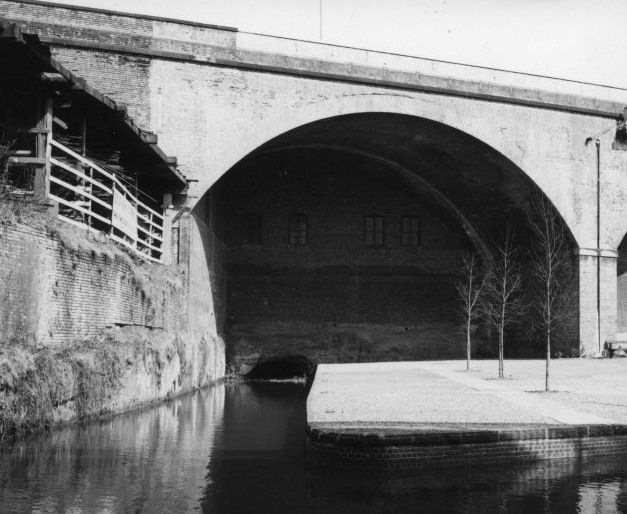

years, Castlefield had been modified considerably. The main water supply to this

end of the canal was the River Medlock. At the end of the basins near Deansgate,

the Medlock plunged into a “siphon”. This is a tunnel that takes the river

beneath the basins to emerge beyond

Potato

Wharf. For unloading, the

boats were steered into a tunnel hewn into the rock face. The river drove a

water wheel that powered a winch used to raise goods from the boats below up to

street level. When the Rochdale

Canal was built, it’s bed

cut across the path of the tunnel, which eventually fell into disuse. The

entrance to the tunnel has been rebuilt, as has the water wheel, whose operation

can be demonstrated by guides showing visitors around the area. Part of the

other end of the tunnel can be seen at

Pioneer

Wharf,

adjacent to Deansgate, as an arch two or three feet above the water level of the

Rochdale

Canal

where

it cut across

the original line of the tunnel.

The entrance to the River Medlock Siphon Tunnel

The truncated section of tunnel can be seen to the left of Pioneer Wharf on the

Rochdale Canal

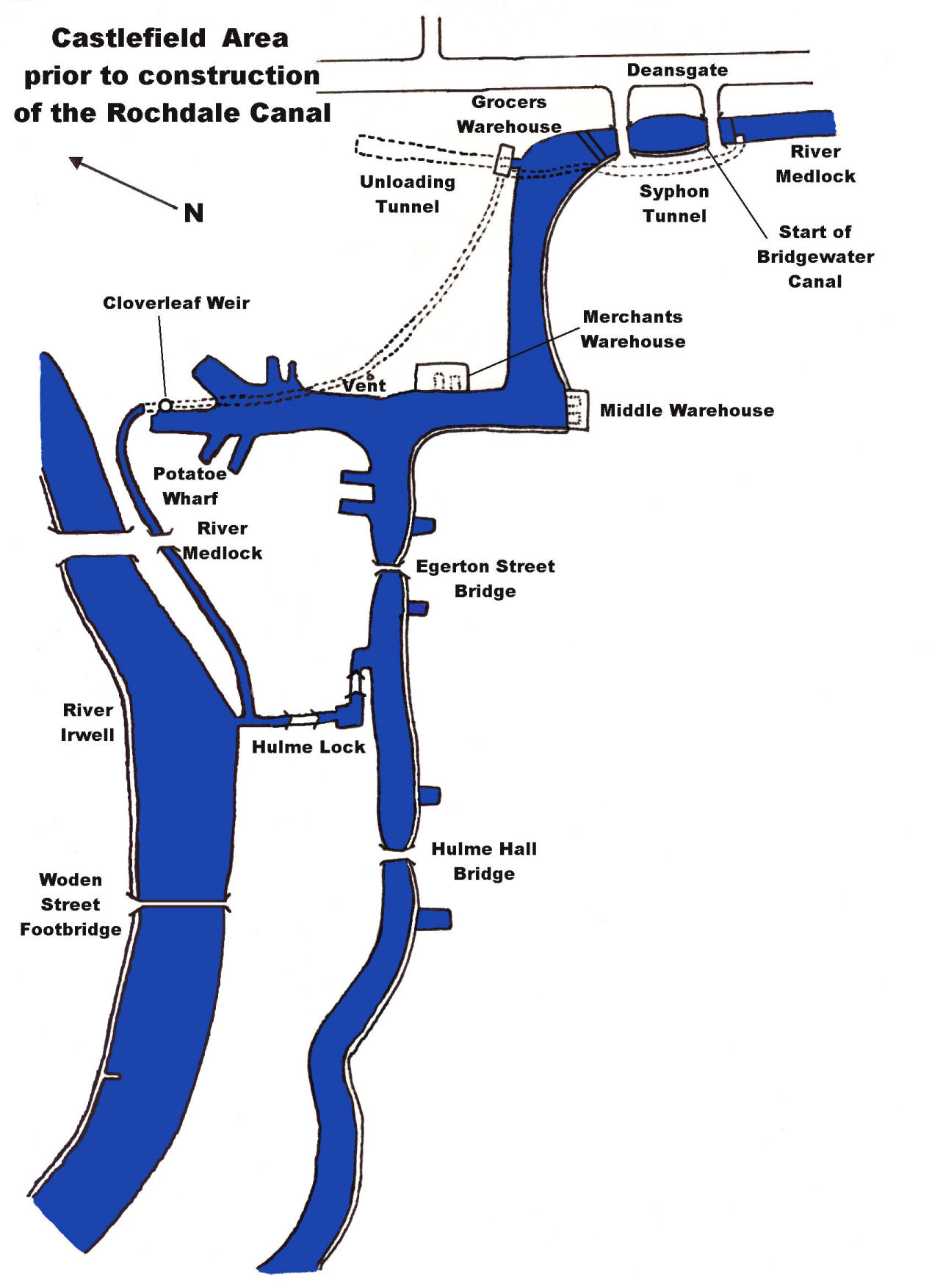

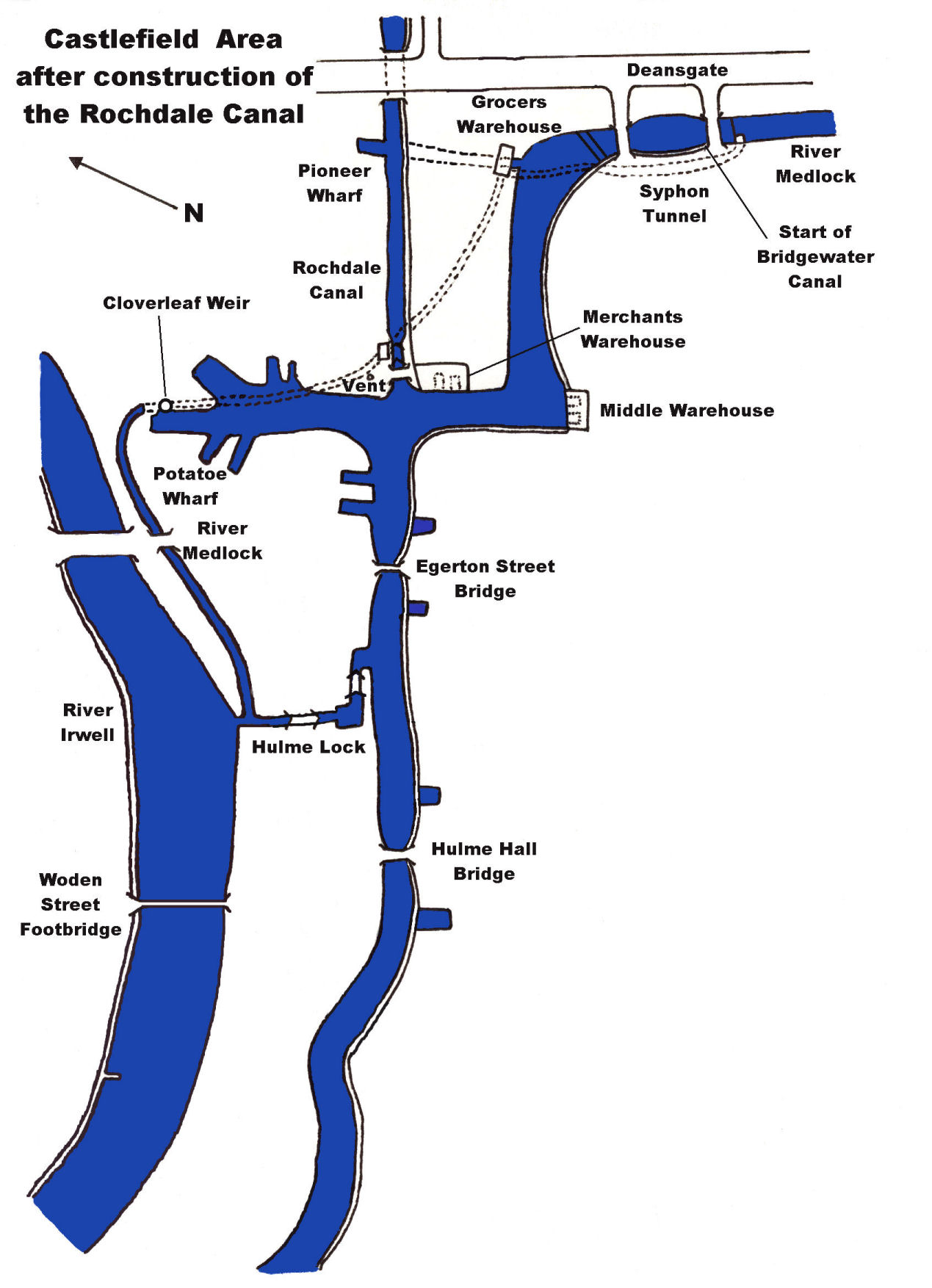

These two maps illustrate how Castlefield Terminus was

modified when the Rochdale Canal was built

The River Medlock emerging from its subterranean journey beneath the Castlefield

Basin Complex

When the

Manchester

Ship Canal

was being constructed in the 1890’s, the siphon method was again utilised to

convey rivers such as the River Gowy at Stanlow and the River Dibbins adjacent

to Mount Manisty beneath the canal. But they were on a much bigger scale than

the one at Castlefield. The Castlefield area is described in greater detail in

the

Castlefield Canal Heritage Walk section of the Canalscape

website.

The River Gowy Siphon on the Manchester Ship Canal under

construction

Another structure that has shrunk in size as the wharves

expanded was Brindley’s original “cloverleaf” weir (so called because of it’s

shape). This weir is located between Potato and Giant's Wharves at Castlefield and returned excess water from the canal to the River Medlock as

it emerged from the siphon. In 1838, most of the weir was removed for two

reasons, one - it frequently blocked, and two - the space was needed for

additional wharves.

A contemporary photograph of Brindley's Cloverleaf Weir at Potato Wharf,

Castlefield

Also in 1838, the Hulme Lock Branch was built. This branch

connected the

Bridgewater

Canal

to the River Irwell adjacent to where the Medlock runs into the Irwell. The

Hulme Lock Branch superseded the previous connection with the

Mersey and Irwell

at Cornbrook known as “The Gut”. The same year also saw the introduction of

experimental steam tugs onto the canal and a proposal for a branch to run from

Altrincham, sixteen miles to Middlewich. It would cross the

Trent

and Mersey

Canal

to join the Middlewich branch of the

Chester

and

Ellesmere Canal

(later to be known as the Shropshire

Union

Canal).

The board of the

Chester

and

Ellesmere Canal

encouraged the Bridgewater Trustees in this proposal but it came to nothing (as

could be expected) due to opposition from the

Trent

and Mersey,

Macclesfield, Peak

Forest

and

Ashton Canals.

A 1930's photograph of the Hulme Lock Branch

Despite the modernisation of cargo handling facilities and

a toll war with the Mersey

and Irwell Navigation, the railways were having a noticeable effect on the

tonnages carried along the

Bridgewater

Canal.

One logical solution to the problem would be to control trade on the

Mersey and Irwell

Navigation. They were having the same difficulties as the

Bridgewater,

as the drop in dividends paid to their shareholders could testify.

Consequently, Parliament was applied to for an Act enabling

the Bridgewater

to purchase the shares of the Mersey and

Irwell. This Act was passed and the transfer of shares took place on 17th January 1846.

The sum paid for the navigation was £550,000.

The "V.I.P. Barge" carrying Queen Victoria in 1851

The

Bridgewater

Canal,

being a commercial waterway was navigated twenty four hours a day, and did not

generally allow pleasure craft on it’s waters. However, there are always

exceptions to the rule, the first taking place in 1851 when Queen Victoria took

a trip along the canal from Patricroft to Worsley were she was to be entertained

at Worsley Old Hall. The queen refused to cross Barton Aqueduct saying that it

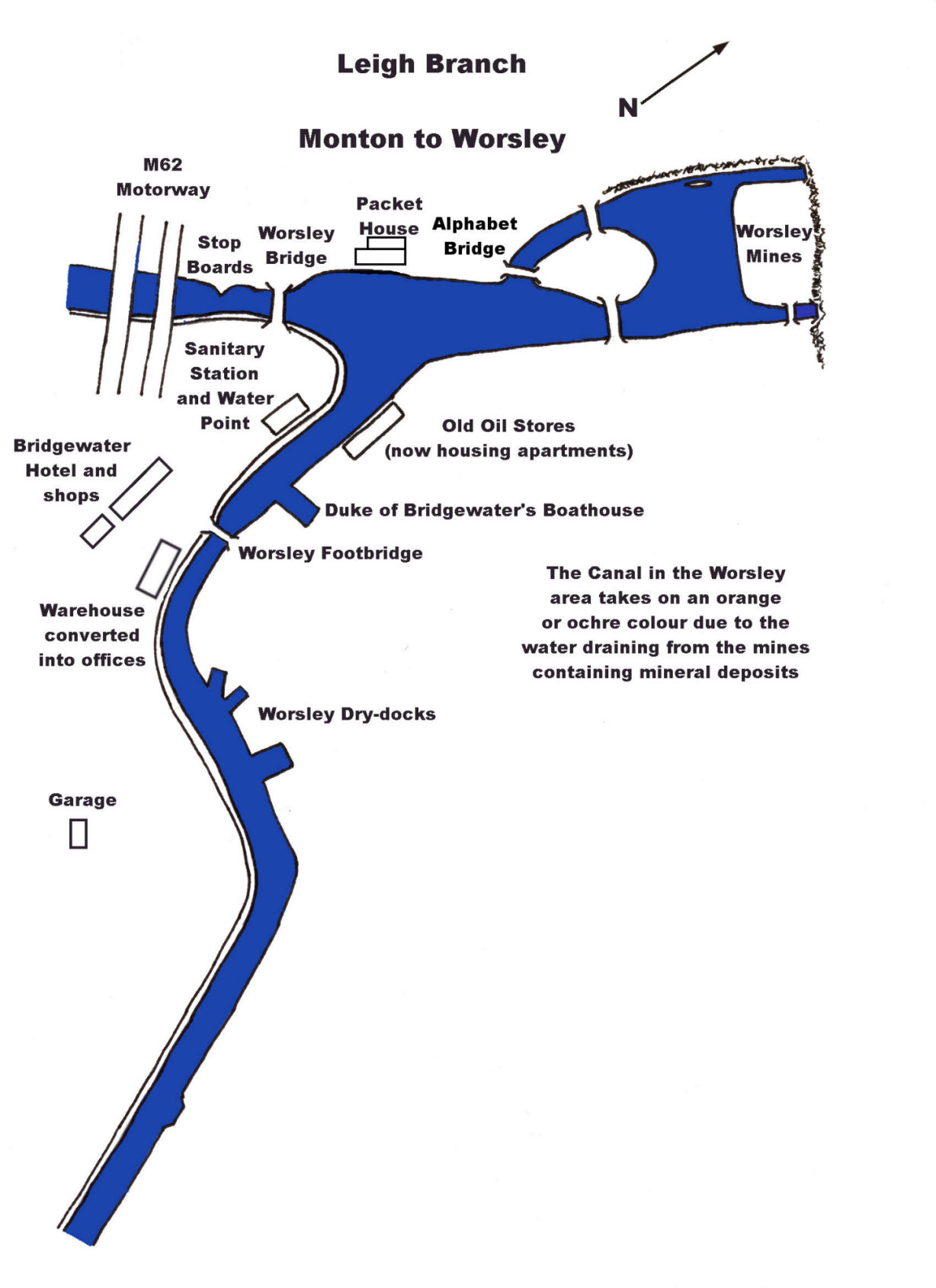

would be more like flying than sailing. The canal’s normal colour at Worsley is

ochre, caused by iron deposits from the water draining out of the mines. The

canal was dyed royal blue in honour of the queen’s visit. The second exception

was in 1869 when the Prince of Wales took a trip from Worsley to Trafford for

the opening of the Royal Agricultural Show. On both these occasions the craft

used was the “V.I.P.” Barge, later to be used as an inspection launch. The boat

was permanently kept at Worsley in the boathouse adjacent to the dry-docks. The

"V.I.P. Barge" is sometimes referred to as the "Duke's Barge" and the "Royal

Barge". It

was later converted to diesel power and was in use up to 1948, when it was

broken up. In later years, the Duke encouraged his rich landowner friends to

have “gondolas” as he called them, built to use on the canal for leisure

purposes.

The "V.I.P. Barge" emerging from the Duke's

Boathouse in Worsley circa 1906

Whilst the acquisition of the Mersey

and Irwell Navigation, no doubt, helped to boost the canal’s financial position

in the face of the railways, it still needed to be competitive. By 1860, the

Mersey

and Irwell was so silted-up that it was impossible for all but the shallowest

drafted craft to reach

Manchester.

Consequently, in 1872, a new company was formed to inject capital necessary for

the dredging of the Mersey

and Irwell and increased warehousing, as well as new cargo handling equipment on

the Bridgewater

Canal.

This also included the purchase of the steam tugs after their successful trials

had been completed. The new company was called the “Bridgewater Navigation

Company Limited”. It is ironical that the many of the shareholders also held

shares in railway companies and that the body collecting shares for the trustees

of the company was a collection of railway companies.

The MSC "Walton"... one of the fames "Little Packets" seen here on

the Manchester Ship Canal

The tugs that were purchased were the famous “Little

Packets”. These were steam-powered vessels, 18.3 mtrs (60 ft) in length, powered

by a single cylinder horizontal engine driving a 1 mtr (3ft) propeller.

Initially, five tugs were ordered and, so successful were they that by 1881

their numbers had risen to twenty six. These vessels were in regular use on the

Bridgewater and adjacent

waterways (hence the 18.3 mtrs/60 ft length) until the 1920’s, when some were

converted to diesel power and the remainder either sold or scrapped. Those

converted to diesel power soldiered on until the 1950’s when more modern

replacements were purchased. For many years, the hull of one of these tugs could

be seen out of the water at one of the “wides” (lakes connected to the canal

caused by salt mining subsidence) on the Trent

and Mersey

Canal

near Middlewich before being bought for restoration. The man behind the

introduction of the tugs was the new General Manager and Engineer of the

Bridgewater Navigation Company Limited, and someone that you will be hearing

more of later… Edward Leader Williams.

A Bridgewater Tug pulling a train of barges through Walton Cutting

Prior to 1865, craft were “legged” through Preston Brook

Tunnel. This involved a plank laid across the bows of a narrow boat on which two

men would lay on their backs and propel the boat through the tunnel by “walking”

along the tunnel roof. Gangs of men were employed solely for this task. In the early part of 1865, steam tugs similar to the type

used for towing on the canal were introduced for tunnel passage duties. Not long

after their introduction, a tug driver and his stoker were overcome by smoke

caused by the lack of ventilation inside the tunnel. Consequently, Mister

Forbes, the Trent and

Mersey

Canal’s

Resident Engineer, ordered four ventilation shafts to be sunk to ease the

situation. Whilst the shafts were being sunk, traffic (including the steam tugs)

continued to pass through the tunnel. In May of 1865, two maintenance workmen

constructing the vents, hitched a work boat onto the end of a train of boats

being towed through the tunnel by a steam tug. They too were overcome by the

smoke, one of which fell into the tunnel and subsequently drowned. At an inquest

into the workman’s death, the Coroner ordered that the tugs must not be used

until the ventilation shafts were completed.

The Preston Brook Tunnel Tug... note the wheels to ensure the tug stays in the

centre of the tunnel

Another type of familiar craft on the

Bridgewater

was the passenger or “Fly” boats that plied the length of the canal daily. One

such craft was the “Duchess Countess” built in 1871.

These specially built light weight narrowboats were pulled

by teams of horses that were regularly changed at the way stations that also

possessed stables. The boats were given priority over other canal traffic and

featured a knife on the bow to sever the tow lines of any boats getting in the

way.

As well as conveying passengers they also carried perishable goods and even

cattle. There was a ring attached to the boat's hold specifically for securing

cattle to.

The "Duchess Countess" on the Bridgewater Canal

The "Duchess Countess" at Lymm in 1927

The

"Duchess Countess" was the last remaining example

of these boats and after retiring from service the home to Mr

Mackey who was a recluse a

recluse before ending her days on the banks of the Llangollen Canal at

Welsh Frankton as a hen house where she was broken up in 1960. There is a

restoration society dedicated to constructing a replica of this historic boat.

The Fly Boat "Duchess Countess" on the canal bank at Welsh Frankton prior

to being broken-up in 1958

The Bridgewater Navigation Company Limited was a fairly

short-lived company. In 1885, the Bridgewater

and Mersey

and Irwell navigations were bought by the newly formed Manchester Ship Canal

Company. The

Manchester

Ship Canal

was proposed by Daniel Adamson, a

Manchester

businessman, in 1882 and was to be a waterway capable of conveying ocean-going

ships from Eastham on the River Mersey to a proposed dock complex close to the

centre of

Manchester.

It would be following the same route as the

Mersey and Irwell

Navigation from Runcorn to

Manchester

with several new cuts and extensions, plus a completely new section from Eastham

on the Wirral to Runcorn, effectively hugging the banks of the River Mersey

Estuary. The plans were very similar to an earlier scheme proposed by Hamilton

Fulton in 1877 and the plan was vigorously opposed by many groups including the

City of

Liverpool who were afraid

that the competition from the Ship Canal would adversely effect the city’s

livelihood. After a long, protracted battle, the Act of Parliament was passed on

the third reading and Lord Egerton cut the first sod of earth on 11th

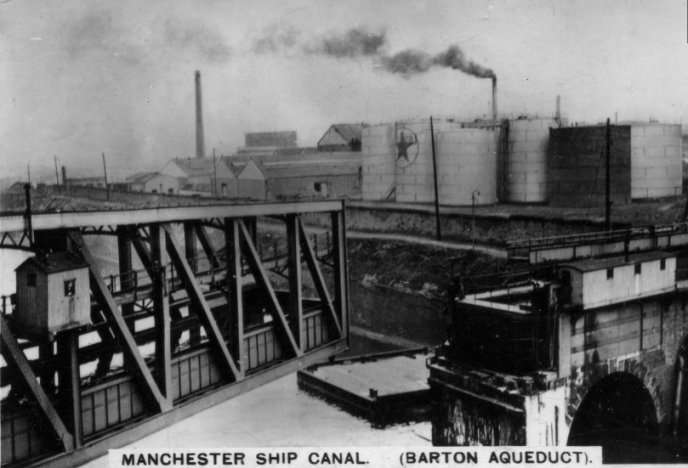

November 1887. The construction of the Ship canal only directly affected

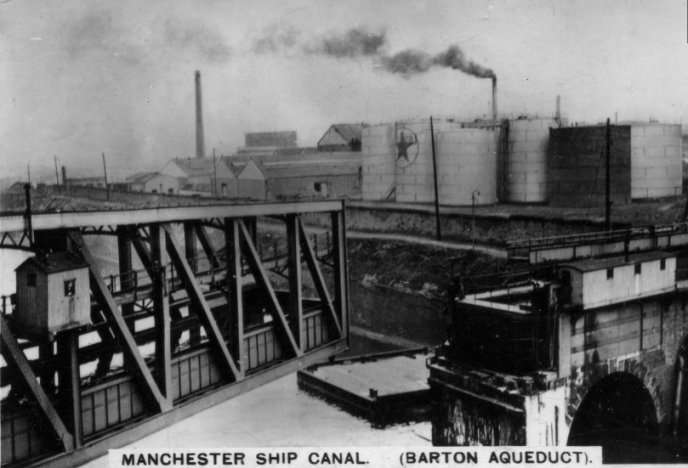

the

Bridgewater

Canal

in two ways. The first was that at Runcorn, access to the River Mersey could

only be gained by crossing the ship canal to Bridgewater Lock or by sailing down

it’s length to Eastham. The second change was at the famous Barton Aqueduct.

This would have to be demolished due to the limited headroom of Brindley’s

original structure.

The original Barton Aqueduct during demolition with the completed Swing

Aqueduct in the background

Projected schemes for the aqueduct’s replacement included

locks to lower craft to the level of the Ship Canal and up the opposite side (as

in the Bridgewater Canal’s original proposal) and a vertical lift similar to

that at Anderton connecting the Trent and Mersey Canal with the River Weaver.

The lift at Anderton was the brainchild of the engineer for the River Weaver who

was, none other than… Edward Leader Williams (although designed and built by

Edwin Clark), the engineer for the Ship Canal. The design that was eventually

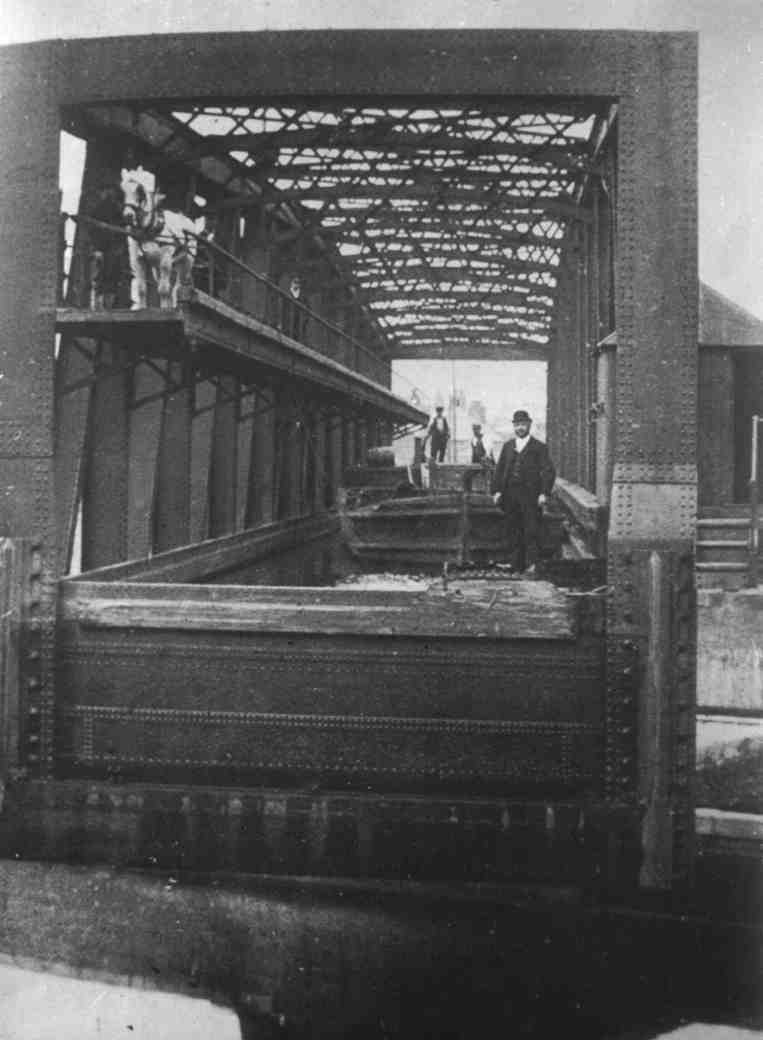

settled on was for a “swing aqueduct”. The Swing Aqueduct and the proposed swing bridges on the Ship

Canal were to be of similar design to the road bridges that spanned the River

Weaver (also designed by Edward Leader Williams). The aqueduct would pivot on an

island built in the centre of the Ship Canal and would swing, full of water, to

allow ships to pass either side. The navigation trough would be sealed at either

end prior to swinging by lock gates to conserve water.

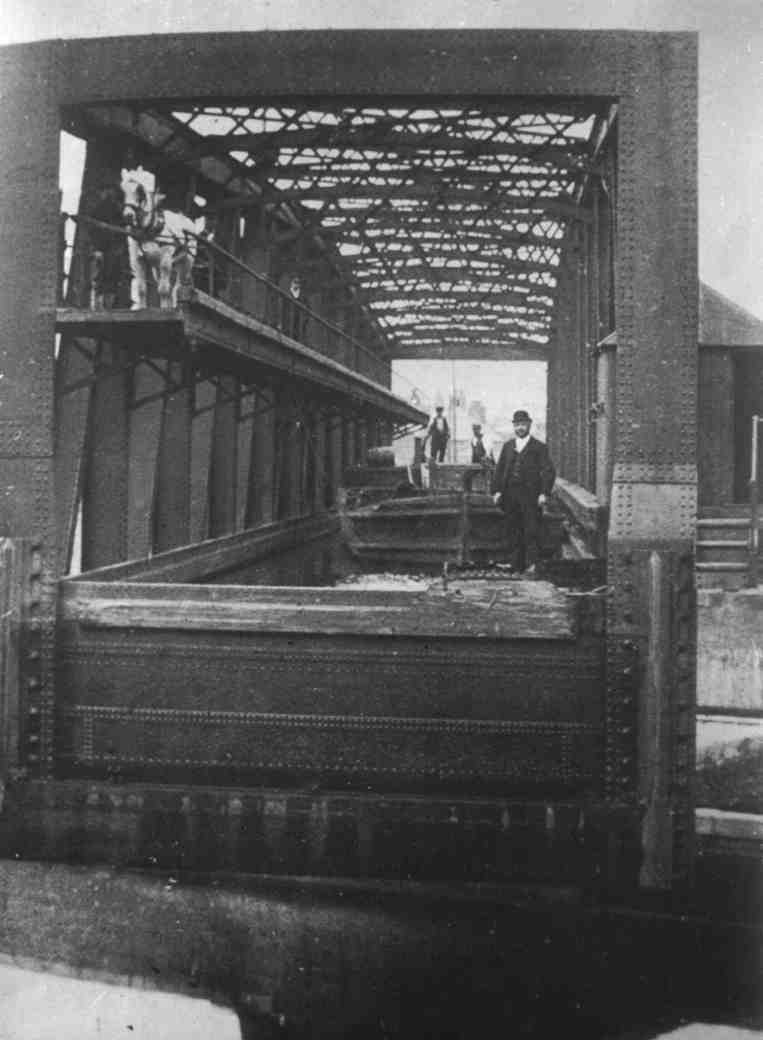

Two different views of

Barton Swing Aqueduct

A rare collectors' card of Barton Swing Aqueduct

Its dimensions are...

Length - 71·6 mtrs (235 feet)

Width - 5·5 mtrs (18 feet)

Depth of water - 1·8 mtrs (6 feet)

Total weight - 1400 tons (800 tons of which is water

Height above Manchester Ship Canal - 11·5 mtrs (38 feet)

A staged photograph showing the aqueduct swung with a boat (complete with

horse and crew) on it

The weight of the aqueduct is supported by 64 steel

rollers, but when swung, a greased hydraulic ram takes some of the weight off

the rollers. The swinging action is achieved hydraulically, being controlled

from a tower on the island that overlooks both the aqueduct and the adjacent

Barton Road

Bridge.

The aqueduct was completed in July 1893 and only then was Brindley’s original

structure demolished in order to maintain

through traffic on the

Bridgewater

Canal.

On the northern bank of the Ship Canal remains part of one of the buttresses and

approach embankments of the original aqueduct in addition to the site of the

Barton Road Aqueduct where the road was spanned by another smaller aqueduct.

Even though Brindley’s original aqueduct was demolished, there remain two similar

structures. The first is adjacent to the Old Watch House at

Stretford. This

is the Hawthorn Lane Aqueduct and even though built on a smaller scale, is

reminiscent of it’s larger brother. With Brindley’s Barton Aqueduct out of the

way, the finishing touches could be made to the Ship Canal in preparation for

it’s opening on

1st

January 1894, having cost £14,347,891 to

construct.

Hawthorn Lane Aqueduct... a scaled down version of the original Barton

Aqueduct

The second is at Prestolee near Bolton on the

Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal. Whilst not built by James Brindley it was

built in 1796 and is similar in construction except for having four arches plus

an "accommodation Arch" allowing access between fields.

The similarities don't end there... it even carries the Manchester, Bolton and

Bury Canal across the same river... the River Irwell.

The Prestolee Aqueduct carries the Manchester, Bolton and

Bury Canal across the River Irwell

Overshadowed by the excitement of the Ship Canal’s opening

was the closure of the Worsley Mines, the original reason behind the canal’s

construction. The two entrance portals gave access to no less than 74 km (46

miles) of subterranean canals serving coalfaces on several different levels. The

miners travelled to the coalfaces by boat

and

down access shafts.

The mined coal was loaded into wooden or iron boxes or containers. The

containers were then loaded into special boats called “Starvationers”, so called

because of their exposed ribs. They qualify as being the first container boats

in existence. The “starvationers” made their way out of the mines loaded with

containers, negotiating the different levels within the mines by means of

subterranean locks or revolutionary inclined planes, also situated underground.

Subterranean canals inside the mines at Worsley

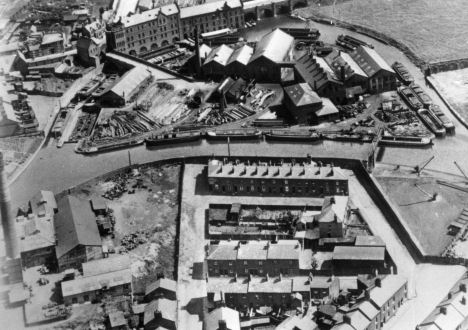

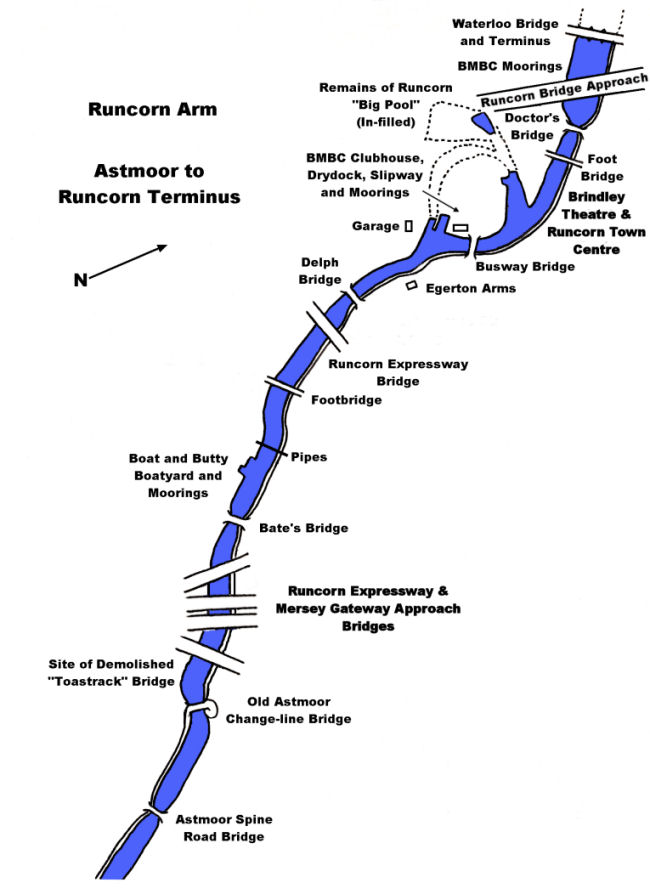

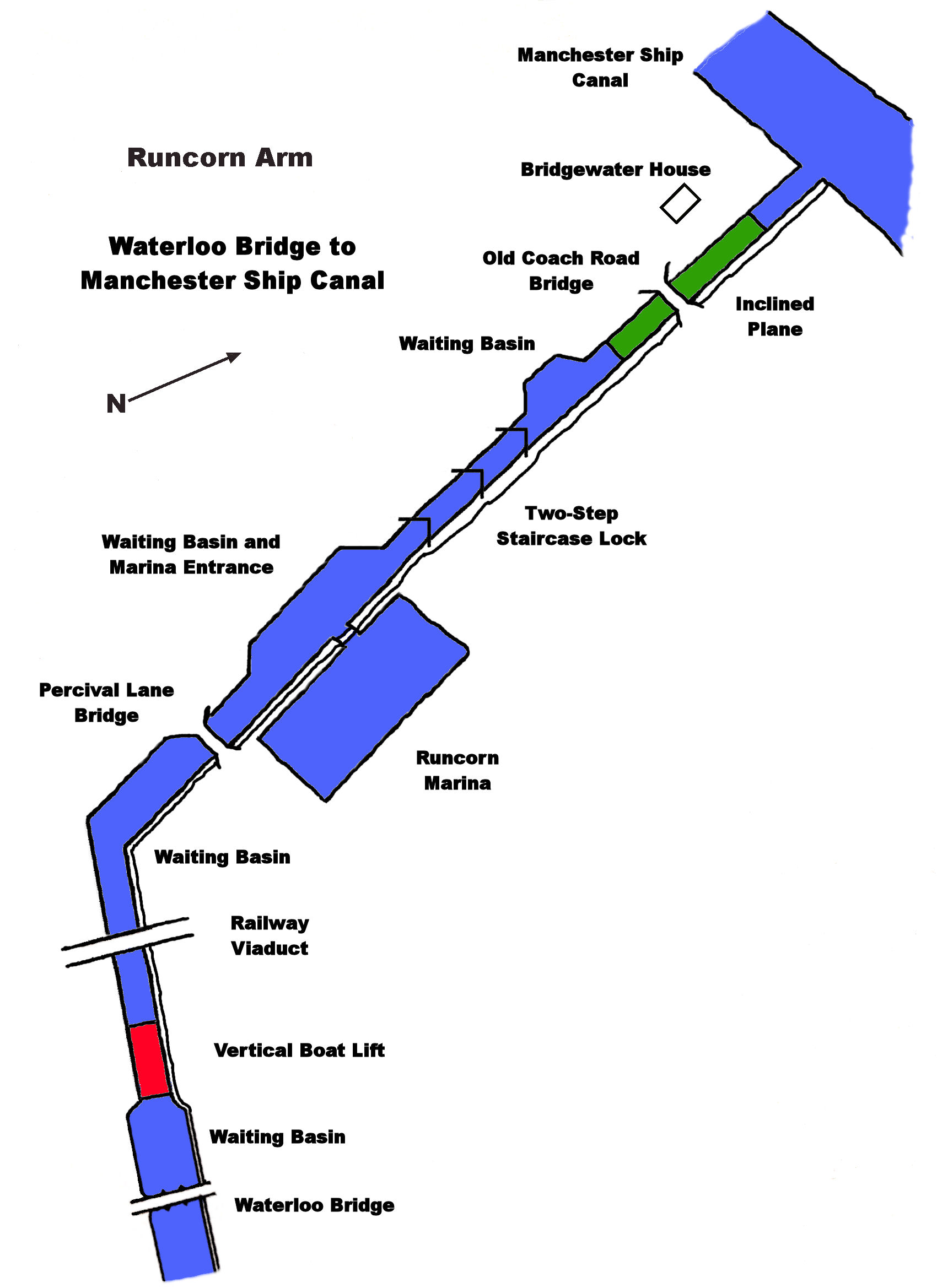

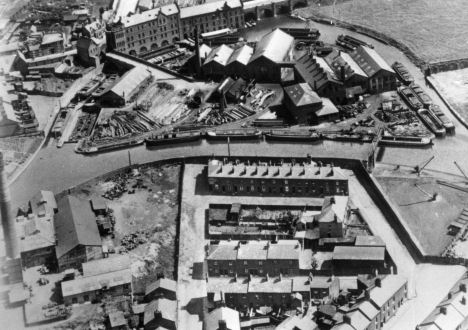

1890 saw the founding of Sprinch’s Boat Yard at Runcorn

along with the straightening of the canal’s route adjacent to the yard.

Originally, the canal swung around a sharp bend going towards Runcorn and passed

next to the “Big Pool”, a natural lake that Brindley took advantage of when

constructing the canal. After passing by the pool, the canal took another sharp

bend before proceeding towards

Waterloo

Bridge

(the present terminus of the canal at Runcorn). When the boat yard was built,

one of the entrance arms to the pool was filled-in and utilised for the location

of a dry-dock and slipway. Access to the pool was retained by the arm north of

the yard. The straightening out of the bends took the canal to the front of the

yard, as it is today. The dry dock and slipway are still in use today, being

controlled by the Bridgewater Motor Boat Club.

In this 1930's aerial view of the Sprinch Boatyard the original line of the canal

can be seen

This contemporary aerial photograph shows the line of the Sprinch Arm and the

location of the Big Pool

(Photograph - Google Earth)

A Sunday School Outing loading at what is now Thorn Marine - Stockton Heath

in the early 1900's

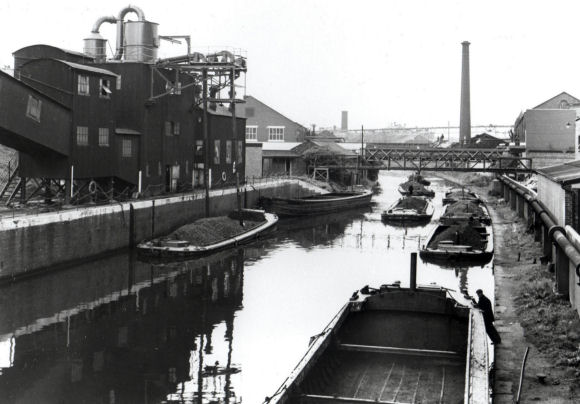

The canal

entered the Twentieth Century uneventfully. Trade was gradually falling and

carried on falling to such a low level that, in 1939, Brindley’s original line

of locks at Runcorn were closed through lack of use, being in-filled in 1948.

Throughout the early part of the twentieth century, the canal between Worsley

and Leigh has been continually affected by mining subsidence. This lead to need

for the canal banks to be reinforced on a grand scale, the work being funded by

the organization responsible for mines at that time - the National Coal Board.

The embanked Bridgewater Canal towering over the subsided landscape near

Leigh

In 1952, new life was injected into the canal by allowing

pleasure craft to use the canal for leisure purposes. Boating clubs started to

spring up along the canal, the first of which was the Bridgewater Motor Boat

Club at Runcorn. Today, their clubhouse stands on the site of Sprinch’s

Boatyard, which burnt down and closed in 1935. Other cruising clubs are situated

at Lymm,

Sale,

Stretford

(The Watch House), Worsley and Preston Brook. Today, most of the clubs have

moorings at more than one location usually of the “linear” variety (along the

side of the canal).

An early boat rally on the Bridgewater Canal in the 1950s

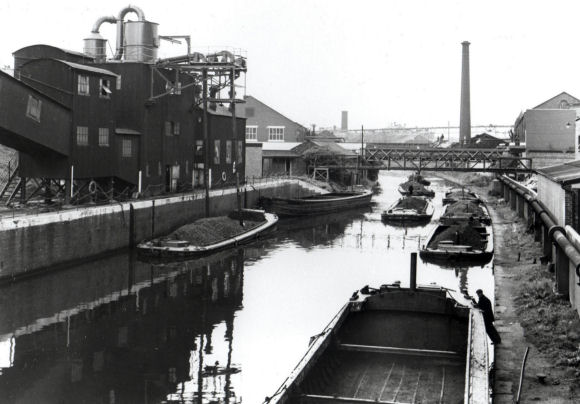

Commercial traffic continued to diminish and in 1966, the

New Line of locks at Runcorn was in-filled, leaving this end of the canal a

cul-de-sac, terminating at

Waterloo

Bridge.

The canal was severed here in preparation for the building of the new Runcorn

Expressway, part of a road network essential to the development of Runcorn New

Town. A little thought from the developers would have enabled the line of the

canal to be retained for possible future restoration.

Basin close to the bottom of the

Old Line of Locks probably in the 1930s

A little further up the locks looking downhill

The same location after abandonment in 1966 with Bridgewater

House just visible on the left

The New

Line of Locks at Runcorn prior to in-filling

Mersey flat being poled through the flight

Looking down the Old Line of Locks

The railway viaduct and lock looking up-hill

The next lock up towards Waterloo Bridge

Waterloo Bridge pre-1966 prior to the infilling of the Runcorn Locks

The site of the old line of locks is still traceable today.

The area had been landscaped and a footpath passes through the centre of what

were the once busy lock chambers. However, when the Mersey Second Crossing (the

new Runcorn-Widnes Bridge) is completed, the approach roads to the original

bridge will be realigned, allowing the canal to be reopened beneath Waterloo

Bridge and connect with the Manchester Ship Canal adjacent to Bridgewater House

(now a College).

A view of how the proposed new Runcorn/Widnes Bridge aka the Mersey Gateway

should have looked.

Note the double-deck design with a light railway or tram lines beneath the road

deck

A photograph of the completed Mersey Gateway Bridge

showing the two older bridges

A

photograph of the completed Mersey Gateway Bridge from the Fiddler's Ferry side

Bridgewater House once stared over a forlorn and overgrown

wasteland. Today it is a college and is surrounded by a development area. The

original lock gates that were removed from the canal when it was in-filled had a

new lease of life when they were utilised on the restoration of the

Upper Avon. Maybe

it will not be too long before the canal at the side of it is in use once more.

Bridgewater House in 1986 prior to regeneration or the surrounding area

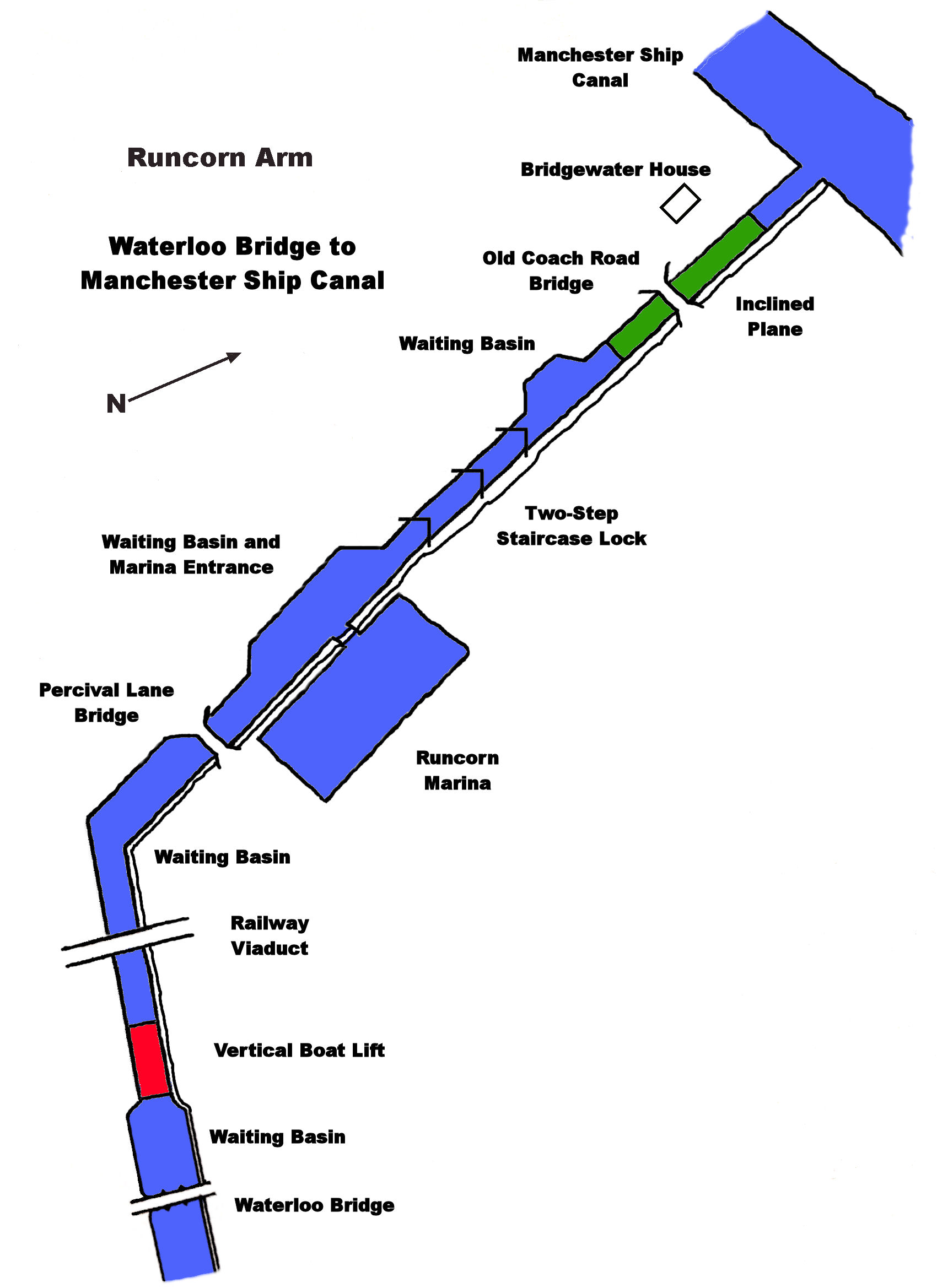

There is a growing amount of interest and support for the

restoration of the canal leading down to the Manchester Ship Canal (see the

route description of the

Runcorn Arm), allowing access at the Runcorn end of the

canal to the

Manchester

Ship Canal

which also connects with

the Runcorn and Weston

Canal

leading to the River Weaver Navigation. Although this restoration would be a

formidable task, bearing in mind the new canal connecting Liverpool’s

Albert Dock to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, the construction of the Ribble

Link on the Lancaster Canal, the restoration of the Anderton Lift, Standedge

Tunnel, the Huddersfield Narrow and Rochdale Canals, it would not be an

impossible or impractical project.

Where the preserved route of Runcorn Locks meets the

Manchester Ship Canal

With the depletion of commercial

traffic on the upper reaches of the Ship Canal, the reinstatement of Runcorn

Locks could create three new

cruising routes for pleasure craft. One, up the Ship Canal to Manchester and

onto the Bridgewater Canal at Pomona Lock. the

second, downstream to

the Runcorn and Weston

Canal

leading to the River Weaver Navigation and onto the Trent and

Mersey Canal via the Anderton Boat Lift which was re-opened to boats at Easter of 2002.

Anderton Boat Lift after restoration

Apart from creating new bridges and closure of the previously

mentioned locks, the Runcorn Expressway also necessitated the filling-in of the

Big Pool. Although part of it still remains, it is not connected to the canal

except by a small drainage culvert. With a little foresight, it could have been

converted into a marina for pleasure craft, but sadly, this was not to be. One

of the arms of the canal that gave access to the Big Pool is used by BMBC for

off-line moorings.

The 1971 breach at Bollington

In 1971, a breach occurred on the embankment over the valley

approaching the River Bollin Aqueduct. As a result, part of the embankment and

aqueduct were swept away. A new channel was constructed using concrete and

steel. The remaining part of the aqueduct was also reinforced and remedial work

closed the canal to through traffic for two years. This was not the only

breach in this area. Earlier in the century there was a breach at Lymm and the

photograph below shows the canal drained where Lymm Cruising Club is today. Note

the entrance to "Lymm Tunnel"... which gave access to the coal wharf beyond.

Breach at

showing where Lymm Cruising Club is today in the early 1900's

Two photographs of coal being unloaded at Barton Power

Station in the 1950's

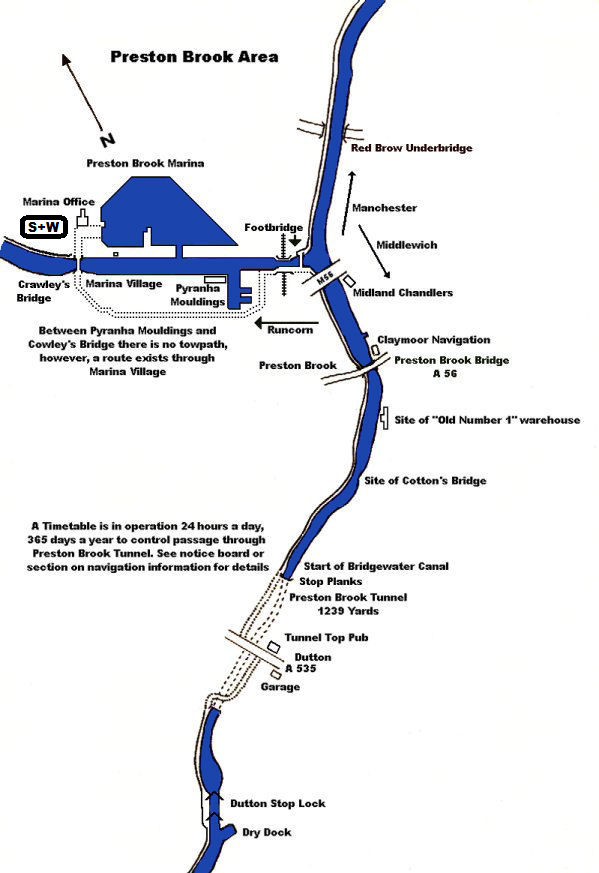

Commercial traffic ceased on the canal in 1974. This

coincided with the opening of a new marina at Preston Brook, opposite the old

Norton Warehouses. Preston Brook Marina offers secure moorings off the main line

for over 300 craft. There is an exclusive housing development on the canal

opposite the marina known as “Marina

Village”,

which successfully integrates the canal into an urban development scheme and was

the first of many such projects to line the canal.

An aerial photograph of Preston Brook Marina

The

occasional commercial narrowboat can still be seen on the canal today,

delivering coal, not to a factory or power station, but for domestic

consumption. These floating coalmen are greatly appreciated by boat owners whose

craft are fitted with solid fuel stoves and enjoy boating out of season.

Derek Brent with "Ambush" delivering gas, fuel and coal

Although not strictly part of the Bridgewater

Canal,

part of Preston Brook Tunnel collapsed in November 1981. A large crater appeared

adjacent to the Post Office above the tunnel. The formation of the crater sent

many tons of debris falling into the tunnel below and damaged a 37 mtrs (121 ft)

long section of the tunnel bore. The Post Office was damaged beyond repair and

demolished, the crater filled-in and the damage to the tunnel was repaired using

concrete sections. The site of the crater is marked on the surface by a round

inspection shaft, the size of which can only be appreciated by looking upwards

whilst passing through the tunnel. The tunnel was re-opened in April 1984, thus

ending two and a half years of isolation for the southern end of the

Bridgewater

Canal

and the northern end of the

Trent

and

Mersey Canal.

The rebuilt section inside Preston Brook Tunnel nicknamed "The Cathedral"

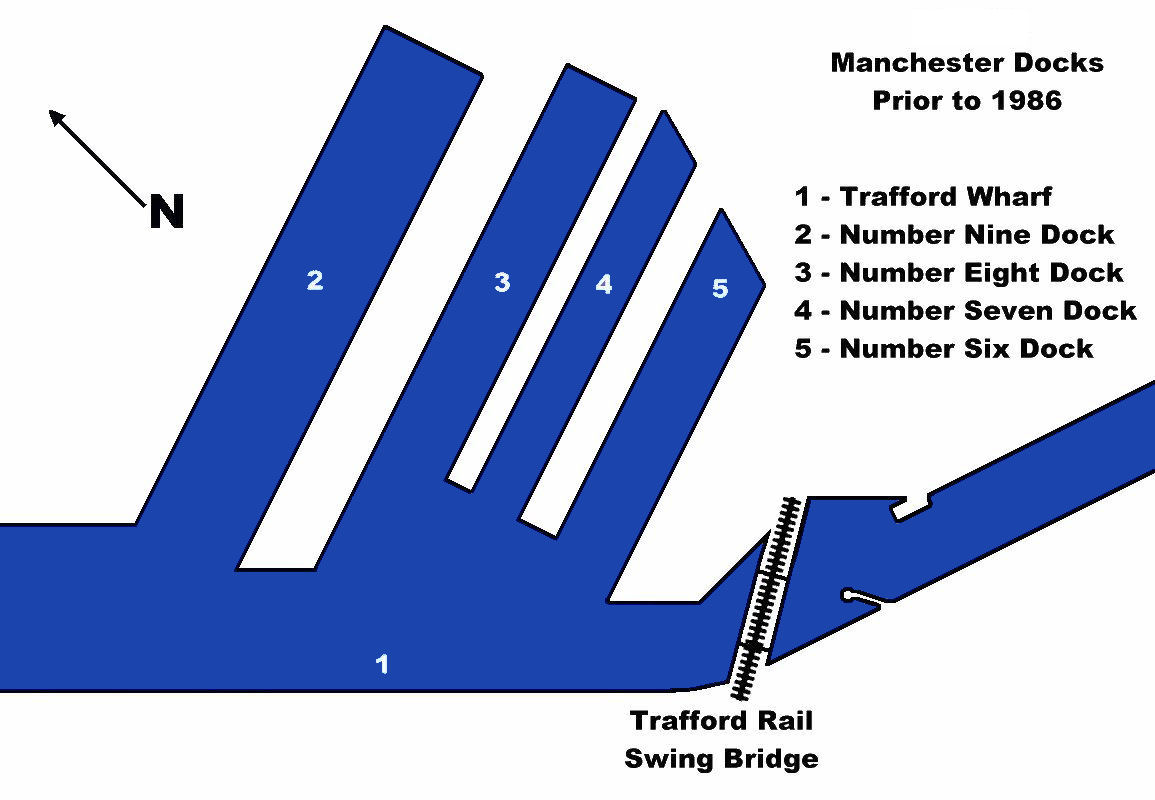

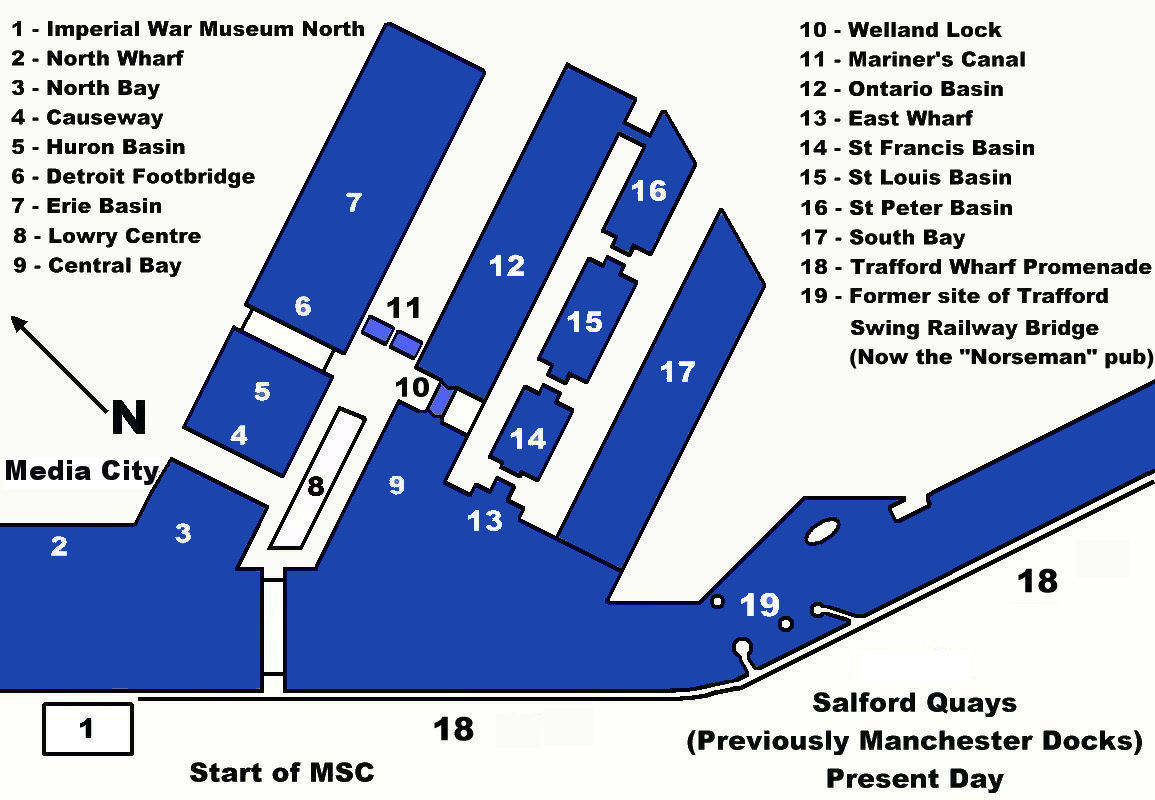

Also in 1984, Bridgewater Estates were purchased by Peel Holdings plc, the

property development company. They also purchased the Manchester Ship Canal

Company shortly afterwards. The traffic on the Upper Reaches of the Ship Canal

had already diminished, leaving acres of quayside and warehouse land ripe for

development. One of their first projects was the construction of an office

development at what is now Salford Quays, followed by the Trafford Centre. The

latter is a prestige shopping centre built adjacent to

Trafford

Park. It features 1.4 million square feet

of shopping area, 280 shops, 35 restaurants, a 20 screen cinema and car parking

space for 10,000 cars. and also a dedicated mooring place for boats that is

monitored by CCTV. Peel Holdings plc also own Liverpool’s

John

Lennon

Airport

and Doncaster’s Finningly Airport.

Inside the Trafford Centre

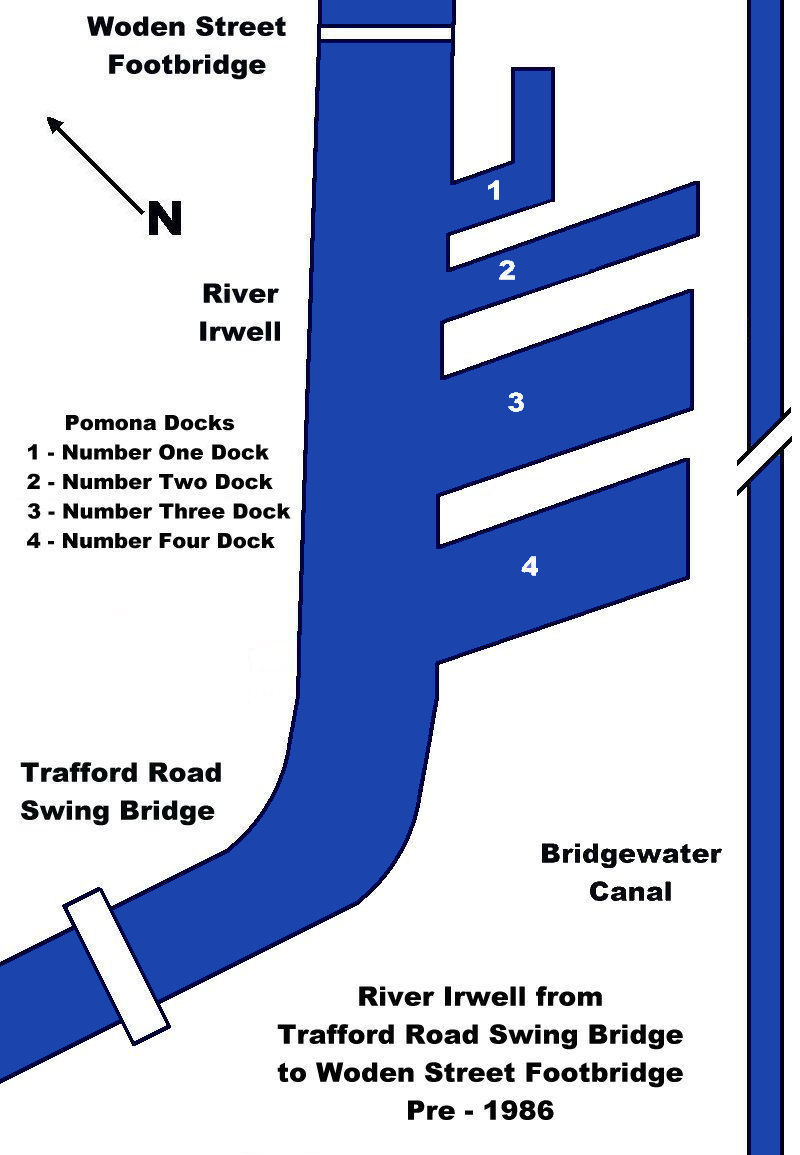

Boats descending Pomona Lock

Today, the

Bridgewater

Canal

is much the same as it was over two hundred years ago. There have been obvious

changes throughout that period, most of which have been previously documented.

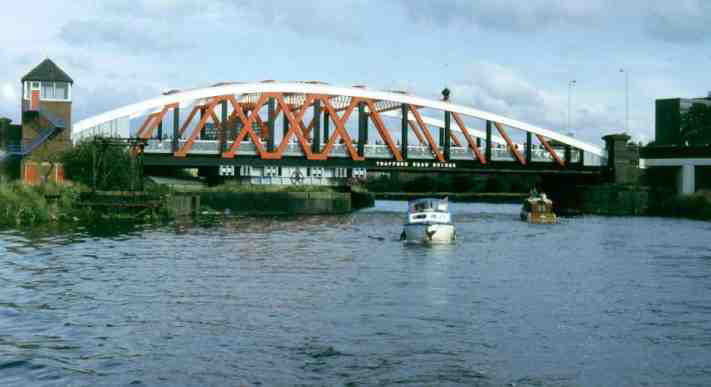

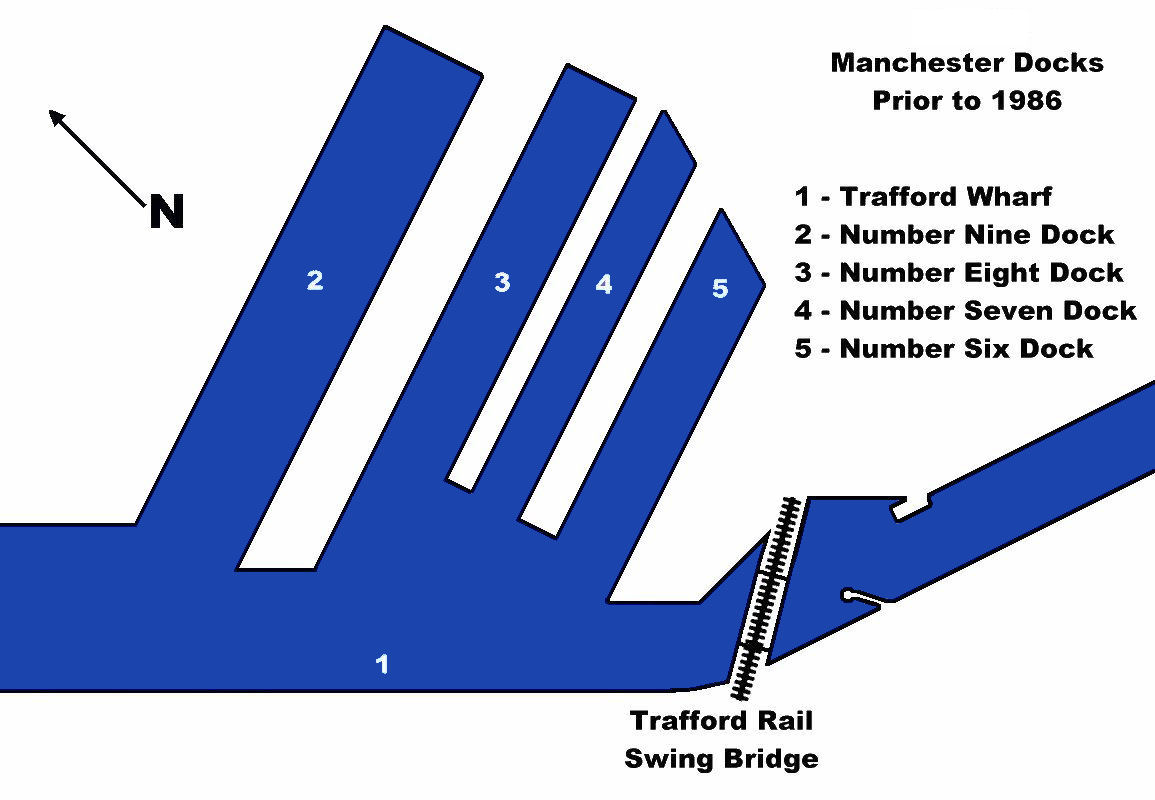

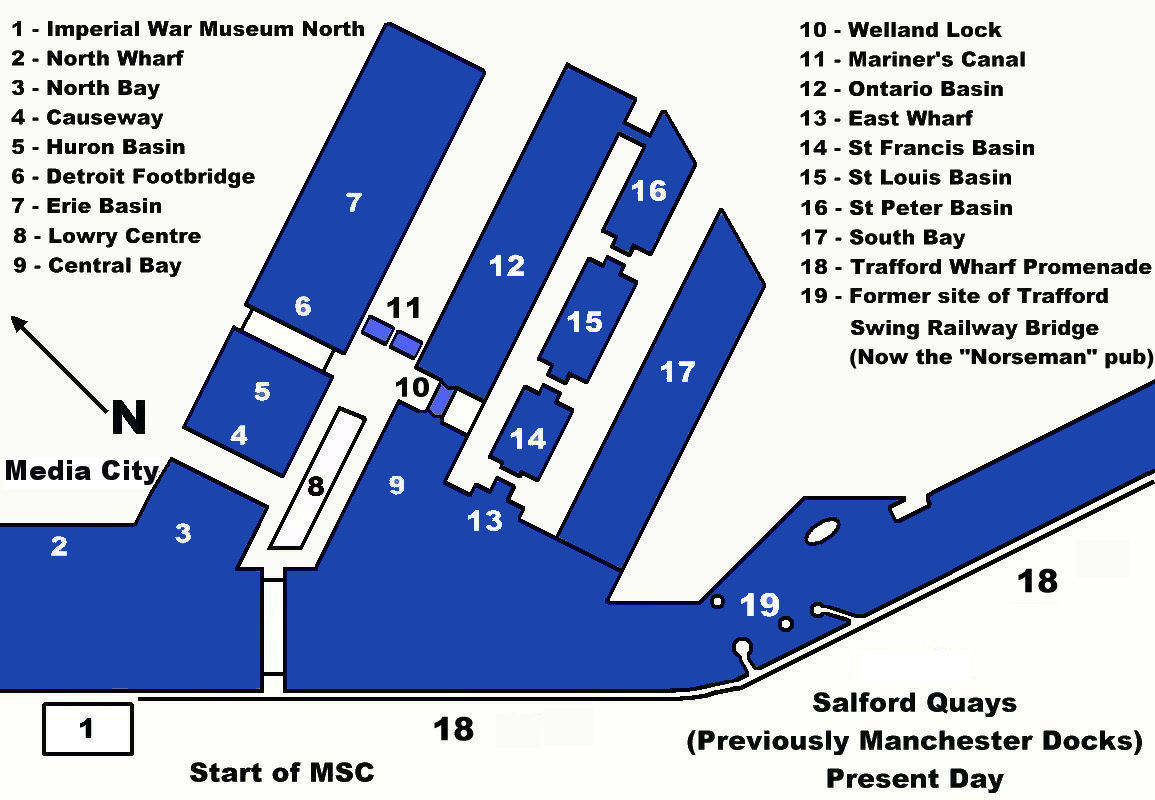

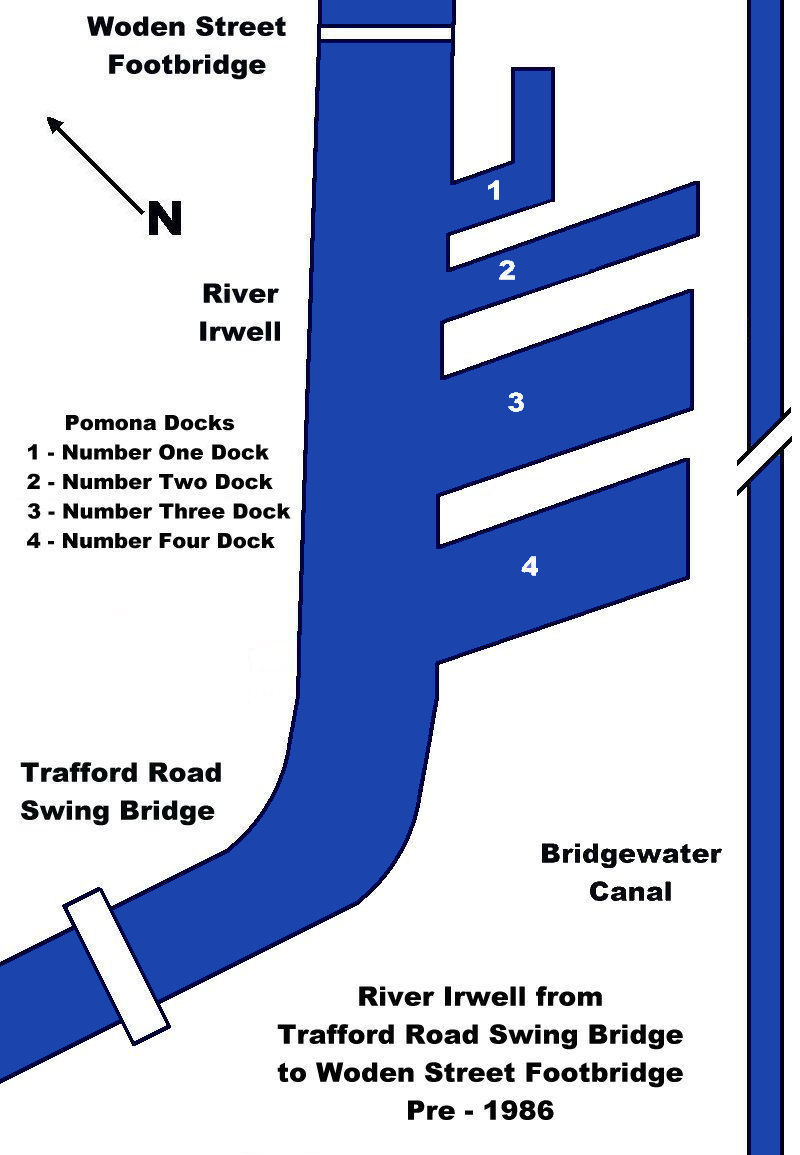

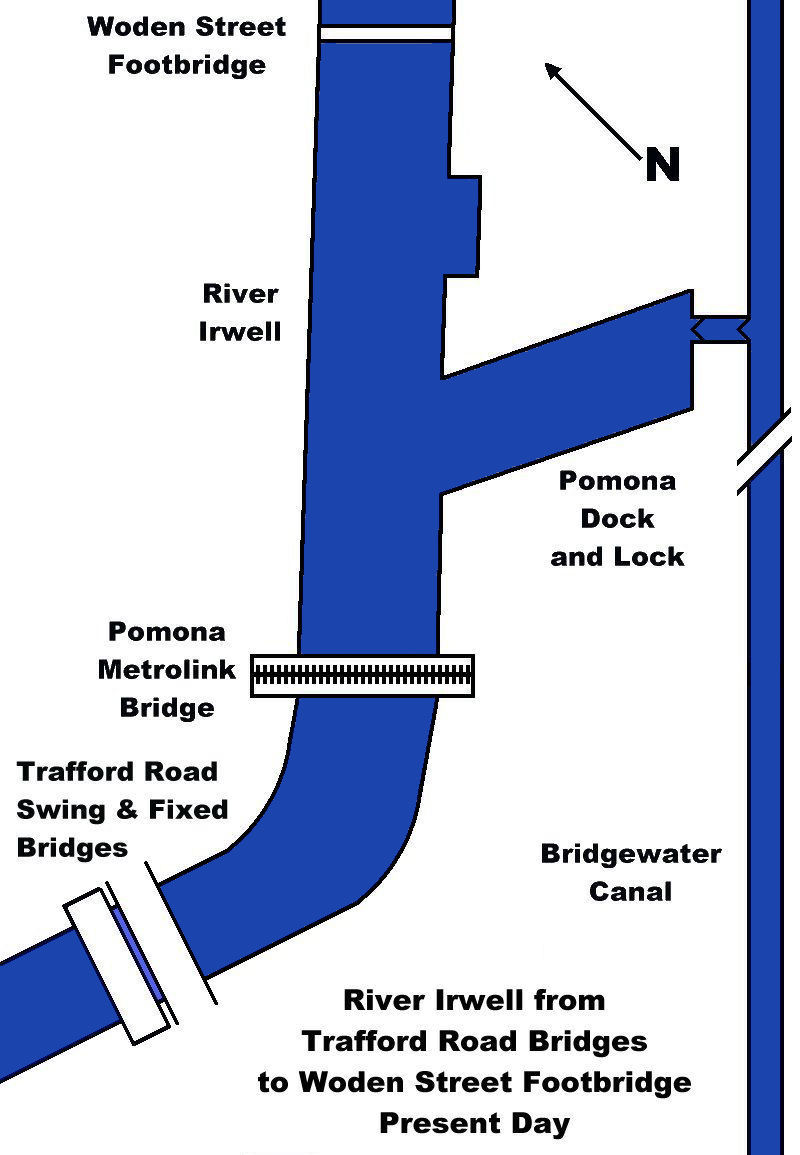

The connection with Manchester Docks via Hulme Lock was replaced in 1995 with

the new Pomona Lock. The new lock gives access to the Pomona Number Three Dock

and is the only lock on the

Bridgewater

Canal

(unless the Runcorn Locks are restored). Castlefield has undergone a radical

change since Peel Holdings took over responsibility for the canal. Some of the

old warehouses have been demolished to make way for modern amenity buildings

such as the Y.M.C.A. and new theme pubs. In a more dramatic vein, the Middle

Warehouse has been completely refurbished and is now used for up-market

apartments, flats and offices. The building also houses

Manchester’s

“Key 103” and “1152” radio stations on the ground floor. The wharf area has been

landscaped and new bridges built to continue the towpath around to areas

hitherto inaccessible. Grocer’s Warehouse has been partially rebuilt and houses

a replica of the water wheel and winch driven by the River Medlock.

Modern developments lining

Castlefield

Developments have taken place at Salford Quays and along

the whole of the Manchester Docks complex the warehouses and factories have been

replaced by buildings such as the Lowry Centre and the new Imperial

War

Museum

– North. Looking towards the future, there are plans to build on the area

adjacent to Pomona Dock and to convert Pomona Dock itself into a marina. These

developments could not be further away from the previous occupants of the area

as the theme of the docks has shifted from industry to business, leisure,

tourism and housing. There may also be a development of the canal adjacent to

the Trafford Centre when the extension to the Metrolink line has been completed.

Pomona Dock and the River Irwell (Upper Reaches)

On

3rd July

2005, a sluice gate adjacent to Potato

Wharf

at Castlefield sprang a leak and emptied millions of gallons of water into the

River Medlock. As it was a Sunday evening and there were no engineers available

to stem the flow of water immediately, millions of fish were put at risk not to

mention narrowboats being stranded in the basins. By the time

the leak was stopped on Monday morning, stop boards had been put in place at

Sale,

Oldfield Brow (situated close to Seaman’s Moss Bridge at Altrincham and Barton

Aqueduct

but

even so, water levels had dropped by over a metre on the main line and

Castlefield Basins were completely emptied. Water levels gradually started to

rise by the middle of the week but it was nearly two weeks before the levels

were deemed “normal”.

The location of the breach between Giant's and Potato

Wharves

A drained Castlefield in July 2005

The ochre

or orange colour of the water at Worsley has been one of the canal's features

since its opening. This was due to a concentration of iron oxide in the water

draining from the mines. In 2004 work commenced on a water treatment plant to

help clean up the water. Water was extracted from the Delph and pumped to the

treatment plant located next to the M62 Motorway Viaduct, treated in a series of

filter beds before returning it to the canal. This plant became operational in

2005 and since then the colour of the water has diminished in intensity.

Outfall from the water treatment plant at Worsley - note the

filter beds in the background

The Bridgewater Canal was host to the 2005 National

Waterways Festival... the second time in twenty years the canal has been the

location of this prestigious boat rally. The Festival was held at

Castlefield in 1988 but, for the 2005 rally, Preston Brook was the

location.

Boats attending the 2005 IWA Rally at Preston Brook

In April of 2009, a new company was formed within Peel

Holdings to look after the administration of the Bridgewater Canal. This company

is known as the Bridgewater Canal Company Limited and operates independently of

the Manchester Ship Canal Company.

The Bridgewater is a deep, broad and (virtually)

lockless waterway that offers a breathing space for the boater before ascending

the Rochdale Nine, Wigan Twenty-One or Heartbreak Hill (the name given to the

climb from Cheshire

into Staffordshire) on the Trent

and Mersey

Canal. The canal is full of contrasts,

from Manchester

to Dunham Massey, or from Runcorn to Walton. These contrasts are enjoyed by many

thousands of people each year and add to the unique character of Britain’s first

waterway to be built independent of a watercourse, Britain’s first true canal… the Bridgewater

Canal.

Return to Contents

|

|

|

84AD

|

Fosse constructed at Castlefield by Romans

|

|

1737

|

Scroop Egerton commissioned Thomas Steers to

investigate making Worsley Brook and mine soughs navigable

|

|

1745

|

Improvements made to River Douglas

|

|

1754

|

Survey to make Sankey Brook navigable by Henry

Berry

|

|

1757

|

Saint Helens

Canal partially open

|

|

1757

|

John Gilbert appointed mine manager at Worsley

|

|

1757

|

Francis Egerton takes up residence at Worsley

|

|

1758

|

James Brindley introduced to Francis Egerton by

John Gilbert and visited Worsley

|

|

1758

|

James Brindley completes survey for

Bridgewater

Canal

|

|

1759

|

First

Bridgewater Canal

Act of Parliament

|

|

01/07/1759

|

Construction commenced on

Bridgewater

Canal

|

|

11/1759

|

Terminus changed from Salford Quay to Dolefield and

the necessary Act of Parliament passed

|

|

17/07/1761

|

Act of Parliament for Barton Aqueduct passed

|

|

1763

|

Terminus changed yet again from Dolefield to

Castlefield

|

|

1763

|

Connection made to Mersey

and Irwell Navigation at Cornbrook (the Gut)

|

|

08/1761

|

James Brindley surveyed the line from

Stretford to Runcorn

|

|

03/1762

|

Act of Parliament passed allowing construction of

line from Stretford

to Runcorn

|

|

07/1765

|

Canal constructed to Castlefield

|

|

1766

|

Act of Parliament passed allowing construction of

the Trent and

Mersey Canal

including deviation of the

Bridgewater

Canal allowing a

junction at Preston Brook

|

|

1767

|

Passenger carrying commenced on the

Bridgewater

Canal

|

|

1768

|

Construction of the new line reached Lymm

|

|

1769

|

Construction at Norton Priory near Runcorn held up

by Sir Richard Brook

|

|

27/09/1772

|

James Brindley died at the age of 56 caused by a

chill aggravating his diabetes

|

|

1772

|

Construction of the locks to the River Mersey at

Runcorn completed

|

|

1772

|

Bridgewater

Canal and Trent and

Mersey Canals

connected at Preston Brook

|

|

1775

|

The disagreement with Sir Richard Brook resolved by

intervention by Parliament, allowing completion of the canal to Runcorn

|

|

01/1776

|

Canal completed at Runcorn

|

|

21/03/1776

|

Canal opened to through traffic

|

|

1791

|

Act of Parliament passed and construction of the

Leeds

and Liverpool

Canal commenced

|

|

1794

|

Act of Parliament allowing construction of the

Rochdale Canal

|

|

1799

|

Old Hollins Ferry branch of the

Bridgewater

Canal at Worsley

extended to Pennington

|

|

1800

|

Rochdale

Canal reaches Castlefield

|

|

1800

|

Ashton

Canal opened

|

|

1801

|

Duke observes experimental tug “Charlotte Dundas”

|

|

08/03/1803

|

Francis Egerton dies, George Gower inherits the

Bridgewater

Estate and a trust set up to look after the

Bridgewater Canal

|

|

1804

|

Rochdale

Canal completed

|

|

1819

|

Act of Parliament allowing extension of the

Leeds

and Liverpool

Canal to be extended to join the Bridgewater

Canal at Leigh

|

|

1821

|

Leeds and Liverpool

and Bridgewater

canals joined at Leigh

|

|

1822

|

Proposal for the Liverpool

to Manchester Railway

|

|

1823

|

Extension of the

Bridgewater

Canal from

Sale to Stockport proposed and objected to by Ashton and Peak

Forest

Canals

|

|

1825

|

Proposal for ship canal from Runcorn to

West Kirby

promoted and subsequently dropped mainly due to cost

|

|

1825

|

Act of Parliament for

Liverpool to Manchester Railway submitted and subsequently

thrown out

|

|

1826

|

Liverpool to Manchester Railway Act of Parliament passed

|

|

1827

|

New line of locks constructed at Runcorn

|

|

1827

|

New warehousing and facilities built at Castlefield

and Preston Brook

|

|

1830

|

Liverpool to Manchester Railway completed

|

|

1833

|

George Gower dies and Bridgewater Estates inherited

by Lord Francis Leveson-Gower, on the understanding that he changed his

name to Lord Francis Egerton.

|

|

1837

|

Lord Francis Egerton and his wife Harriet take up

residence at Worsley

|

|

1838

|

Hulme Lock branch built superseding the previous

connection to the River Irwell… The Gut

|

|

1838

|

Experimental steam tugs introduced into the

Bridgewater

Canal

|

|

1838

|

Proposal for extension from Altrincham to

Middlewich

|

|

17/01/1746

|

Act of Parliament allowing the

Bridgewater

Canal to purchase the

shares of the Mersey and Irwell

Navigation

|

|

1851

|

Queen Victoria travels along

the Bridgewater

Canal from Patricroft

Station to Worsley

|

|

1865

|

Steam tugs introduced for towing through Preston

Brook Tunnel

|

|

1869

|

Prince of Wales travels on the

Bridgewater

Canal from Worsley to

Royal Agricultural Show at Trafford

|

|

1872

|

Bridgewater Navigation Co Ltd formed to raise

capital for investment into Mersey and Irwell Navigation and

Bridgewater Canal

|

|

1877

|

Hamilton Fulton proposes a ship canal to

Manchester

|

|

1882

|

Manchester

Ship Canal proposed by Daniel Adamson

|

|

1885

|

Bridgewater Navigation Co Ltd purchased by newly

formed Manchester Ship Canal Co

|

|

11/11/1887

|

Construction commenced on

Manchester

Ship Canal

|

|

1890

|

Sprinch’s Boatyard opens at Runcorn

|

|

01/01/1894

|

Manchester

Ship Canal opens

|

|

1894

|

Worsley mines close

|

|

1935

|

Sprinch’s Boat Yard burnt down

|

|

1839

|

Old Line of Locks at Runcorn closed

|

|

1948

|

Old Line of Locks in-filled

|

|

1952

|

Pleasure craft allowed on the

Bridgewater

Canal

|

|

1952

|

Bridgewater Motor Boat Club formed at former

Sprinch’s Boat Yard site at Runcorn

|

|

1966

|

New Line of Locks in-filled at Runcorn

|

|

1971

|

Bollin Aqueduct breach

|

|

1974

|

Commercial traffic ceases on

Bridgewater

Canal

|

|

1974

|

Preston Brook Marina opens

|

|

11/1981

|

Preston Brook Tunnel collapses

|

|

04/1984

|

Preston Brook Tunnel re-opens

|

|

1984

|

Bridgewater Estates purchased by Peel Holdings

|

|

1987

|

Development at Castlefield commences

|

|

1988

|

IWA National Rally held at Castlefield

|

|

1995

|

New Pomona Lock replaces Hulme Lock as connection

with the River Irwell and Manchester Docks

|

|

2005

|

Breach at Castlefield on 3rd July. In

August the National Waterways Festival took place at Preston Brook and

the new Water Treatment Plant was completed at Worsley

|

|

04/2009 |

The Bridgewater Canal Company Limited formed within

Peel Holdings to

administer the canal independently from the Manchester Ship Canal

Company Limited |

|

14/10/2019 |

Mersey Gateway Bridge opened for traffic by HM Queen

Elizabeth 2nd |

|

03/2020

|

Jubilee Bridge access road bridge at Waterloo Bridge

removed allowing reinstatement of the canal down to the Manchester Ship

Canal

|

Return to Contents

Description

of the Bridgewater Canal’s Route

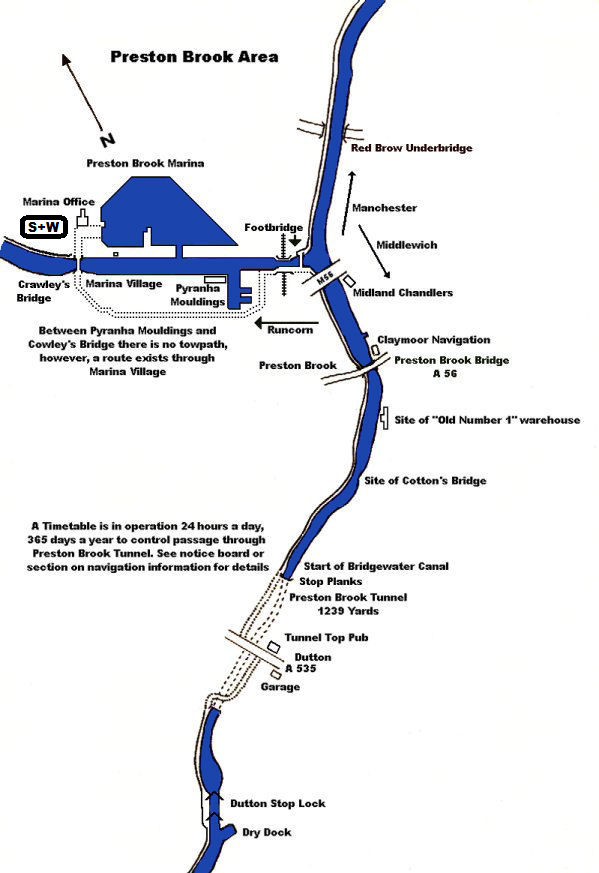

The first Trent and Mersey Canal milepost above Preston Brook Tunnel

The

northern portal of Preston Brook Tunnel marks the beginning of the Bridgewater

Canal. The tunnel is 1133 metres (1239 yards) in length and navigation at all

times (24 hours a day, 365 days a year) is controlled by a timetable due to not

being able to see one end from the other. Northbound entry is from twenty past

the hour until half past the hour whilst southbound entry is from ten to the

hour until the hour.

The northern portal of Preston Brook Tunnel

The cutting leading from Preston Brook Tunnel

A little way along the horse path across the top of the

tunnel is a public house appropriately named the Tunnel Top (formally the

Stanley Arms) which cooks excellent meals in addition to selling alcohol. Across

the road from the pub can be seen the new ventilation and access shaft built

when the tunnel collapsed in 1981. Soon after emerging from the tunnel, adjacent

to the site of the demolished Cotton’s Bridge was Preston Brook Station

although, today, there are no remains of it left. The Old Number One was one of

the few remaining warehouses at Preston Brook. In it’s post-warehouse roll it

has been a nightclub and a restaurant but is now rebuilt as a prestige housing

project. It lapsed into it’s previous condition after being gutted by fire. It

has also featured prominently in an episode of Granada Television’s series

“Travelling Man” which was almost exclusively shot on the Bridgewater

Canal.

The "Old Number One" is now converted into luxury apartments

Claymoore Navigation, adjacent to the