An expanded version of the History Press (formally Tempus Publishing) Book by Cyril J Wood in eBook format

![]()

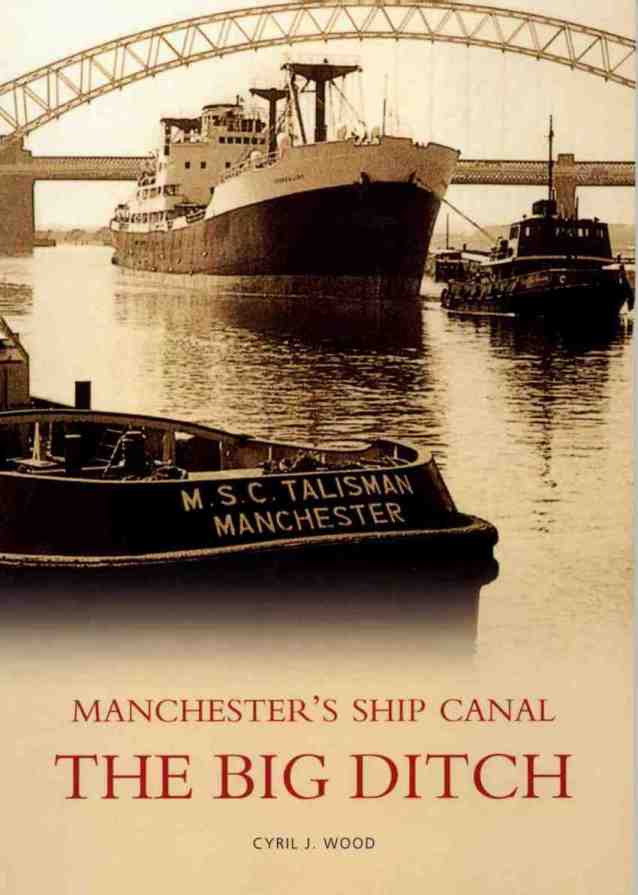

"The Big Ditch - Manchester's Ship Canal" front cover

eBook and Website Version Preface

Introduction

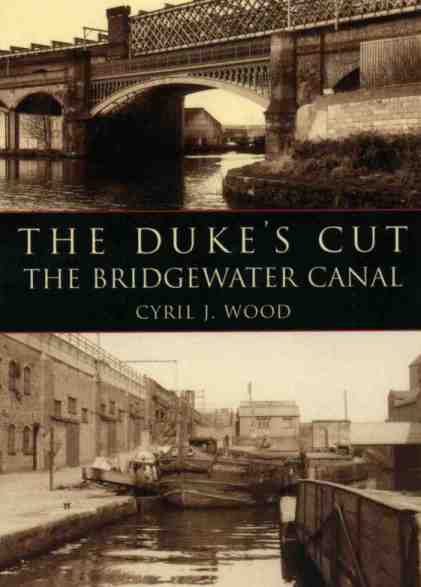

Following the success of my first book... "The Duke's

Cut - The Bridgewater Canal it seemed logical to produce a companion book on

its sister waterway... the Manchester Ship Canal or, as it is more fondly

referred to “The Big Ditch”.

The histories of the two waterways are linked in many ways as is the

geography and the sharing of their ultimate destination; the City of

"The Duke's Cut - The Bridgewater Canal" front cover

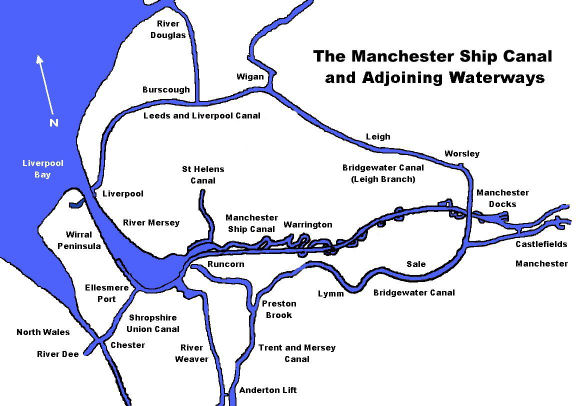

If you look at any map of the MSC’s route you will see the

remains of the many waterways that were connected with it in some way (both

in the physical and historical sense).

The area around

The route of the MSC and adjoining waterways

I hope that you, the reader, find this book a readable, informative and entertaining piece of work that relates the MSC’s history, describes its route, gives invaluable information to those wishing to use it and cruise it. Many of the features and locations that were once familiar have disappeared or have changed beyond recognition. Some of these features have been described and photographed for future generations. I also hope that the book refreshes forgotten memories for older readers that knew the MSC as it was in its heyday and gives a new perspective to the younger readers who have never visited it or only know these features as they are today.

I apologize beforehand for any inaccuracies that may have crept in to the text or maps. No doubt, I will have omitted some details, incidents or happenings that would have been worthy of inclusion, for this I also apologise but you can always contact me via email and I’ll try to include the corrections or additional information in future versions. Throughout the text the "Manchester Ship Canal" is referred to as the "MSC".

Chapter 1 - The History of the Canal

The history of the MSC can be traced

back many thousands of years to the Stone Age.

When the MSC was being constructed in the 1890’s dug out canoes were

discovered at two locations throughout its length where a river previously

existed. Whilst the owners of these

canoes could not have had any direct bearing on the canal as it is today,

their discovery may indicate that the importance of the Rivers Mersey and

Irwell was recognised when mankind was in its infancy.

Two photographs of dug-out canoes discovered at Latchford and Barton in 1889 when the MSC was being built

The first purpose-built inland navigations in

Caer (or Carr) Dyke near Lincoln

(Photograph - Richard Croft)

The Itchen Dyke near Winchester

Over successive centuries, there have been other attempts to produce workable navigations, some of which became successful and still survive today. The erroneously named Exeter Ship Canal (which could only accommodate barges not ships) constructed in 1566 by John Trew ran alongside the River Exe. It was originally constructed to by-pass a section of the River Exe notorious for shoals and scours, connecting Exeter to the sea. This navigation features the first pound locks (as against flash locks) in England. The invention of the pound lock is often attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci but there have been locks of this type in Holland since the fourteenth century and previously, the Grand Canal in China, well before Da Vinci’s birth.

The Exeter Ship Canal

One of the busiest natural inland waterways in the country was the River Severn. It is not surprising that it should figure somewhere in the development of the Inland Waterways system. Two notable navigations connected to the Severn are the Dick Brook and the (Worcestershire) River Stour Navigation, both built by Andrew Yarrington. These navigations provided transport of raw materials and finished articles to and from the industrial areas that sprouted along the banks of the Severn. The Dick Brook is notable as being a small stream near Stourport that was made navigable to access Yarrington’s foundry and workshops and possessed some of the earliest pound locks constructed in this country.

Andrew Yarrington's canalisation of the Dick Brook runs into the River Seven

(Photograph - Philip Halling)

The River Thames was also a river that had been modified with flash locks at first and pound locks in later years. A waterway connecting with the River Thames; the River Lee, now part of the Lee and Stort Navigation, has the distinction of being the first waterway in England to apply for an Act of Parliament in 1424 to allow improvements made for navigation. Although not directly concerned with inland navigation, the last addition to the Thames was the Thames Barrier, a movable tidal and surge flood barrier constructed at Woolwich in 1982 and is the largest movable flood barrier in the world, spanning 520 metres (one third of a mile).

The Thames Flood Barrier

It is interesting to note that a tidal barrier or barrage, complete with sea locks, hydro-electric power plants and a dual carriageway road across the top, has been proposed on many occasions to span the River Mersey estuary between Wallasey and Liverpool. Unfortunately, the scheme has never progressed past the planning stage due to a number of reasons, the main ones being cost, damage to the river’s scouring (self-dredging) effect and ecological concerns regarding the wildlife on the river’s marshes and mudflats upstream from Eastham where the MSC starts.

There has

always been a natural water connection between

The Romans

were the first to realise the importance of river navigation in the area and

must have experienced considerable difficulty navigating the River Mersey,

especially between

Roman Fort remains at Castlefield

The confluence between the Rivers Irk and Irwell in Manchester

Little is known or

documented about the craft that navigated the Irwell and

An early photograph

of a

Note the gas lamp to aid night-time navigation

From Medieval times navigation on the River Mersey was controlled by millers who had constructed dams across the river to maintain a sufficient head of water to turn the water wheels that powered their mills and fishermen who also constructed weirs across the river to retain fish for ease of capture. If craft wished to pass one of these dams they had to navigate through temporary gaps in these weirs known as flash locks. The passage of the flash lock was a dangerous procedure and very wasteful of water. When navigating a flash lock, a gate would be opened and if navigating downstream, the water passing through the gap in the dam would “flush” the craft through. When navigating upstream, craft had to be towed or winched through the gap against the flow of water. Both manoeuvres were dangerous, especially when the river was in flood and consequently, many sailors were injured or even killed as well as craft being lost or damaged. Accordingly, passage was not actively encouraged in order to maintain a sufficient head of water in the millraces to ensure operation of the water wheels and the retention of fish stocks retained by the dam.

Photograph of a flash lock reproduced from an old postcard

The first reference to the possibility of making a more direct water route between Liverpool and Manchester came in 1697 when Thomas Patten of Bank Hall, Warrington, remarked in a letter to another businessman, Richard Norris of Speke near Liverpool, about how beneficial it would be to remove all the weirs on the River Mersey upstream of Warrington, install locks and allow consistent and safe navigation to Manchester. Patten is reputed to have made a start on the project below Warrington allowing two thousand tons of merchandise a year to be transported to Warrington by water. Most rivers and navigations have their own type of craft that is peculiar to the area. The Thames had its Lighters, the Severn had its Trows, the Humber had its Keels. The Mersey was not exempt from this trend and the craft indigenous to the river were called Flats. They were capable of navigating the tidal waters of the Mersey and Dee estuaries as well as coastal journeys and occasionally ventured as far as the Isle of Man and even over to Ireland. The usual set-up was for a gaff rig fore and aft although this design varied. Sail was also used on inland waterways when conditions allowed, although their masts had to be dropped to allow passage beneath bridges. When sails were not practical either due to weather or other conditions, the flats were usually towed by teams of men or, in later years, horses or tugs.

A Mersey Flat on the Weaver Navigation at Weston Point

Narrow and broad locks beside each other at the Boat Museum, Ellesmere Port

As we have seen, Thomas Patten is accredited for the first steps towards making the Mersey navigable. However, in 1712, Thomas Steers, who was responsible for the construction of the Newry Canal in Ireland, Liverpool’s first docks and improvements to the River Weaver, made a survey of the Rivers Mersey and Irwell that would allow unimpeded navigation for craft to Manchester. Following his suggestions, a group of businessmen referred to as the “Undertakers” formed the Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company (unofficially known as the “Old Quay Company” due to its location at Old Quay in Warrington). In 1721 they applied to Parliament for an Act to allow the navigation’s construction. The Act was passed and construction commenced but the project was hampered due to lack of finance.

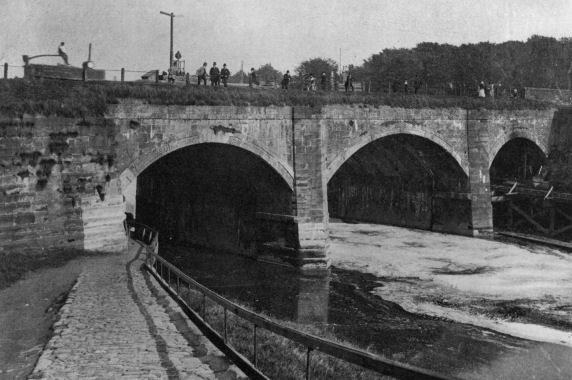

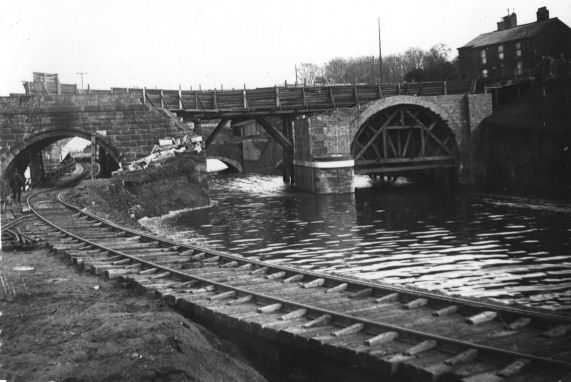

Brindley’s original

Barton Aqueduct carrying the

Note the Mersey Flat negotiating the left

hand arch which lead to Barton Lock

The raising of the River Irwell’s water levels caused difficulties associated with crossing the river. Bridges had to be replaced with new ones featuring arches possessing greater headroom, which would allow the passage of boats larger than previously encountered on the river. Similarly, fords had to be replaced. Notably, Trafford Ford had to be replaced with a free ferry. These problems plus the lack of finance prolonged construction and the navigation was not completed until 1736 when craft could navigate as far as Blackfriars Bridge in Manchester. Four years later in 1740, the navigation was extended to Hunt’s Bank which is still the head of navigation today.

Hunts Bank - the head of navigation on the River Irwell

In 1757

Francis Egerton proposed the building of a canal from his coal mines at

Worsley near

A contemporary photograph of the Bridgewater Canal's Terminus at Castlefield, Manchester

Several

engineering hurdles had been crossed and the canal had reached a major

obstacle, the

Runcorn Locks which once connected the Bridgewater Canal to the River Mersey and later the Manchester Ship Canal

Another canal that started in the

Runcorn locality was the Runcorn and

Remains of the Runcorn and Latchford Canal near Old Quay - Runcorn

The tidal River Mersey at

A closer view reveals the lock details, an abandoned boat and Mersey Flats

An in-filled lock on what was the

A photograph from the 1920s showing barges on the “Black Bear Canal”... part of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation in Warrington

The lower

reaches of the canal can still be traced in the marshland at Runcorn between

the Ship Canal and the

This modern aerial photograph shows the MSC in the foreground, Woolston New Cut at the top and the meander in the centre

1822 saw

a proposal for a railway from

Wallasey and Birkenhead Docks in 1986

He made this comment due

to Wallasey Pool, the location of today’s Wallasey and Birkenhead Docks,

being a natural harbour as against

The now disused

Hulme Lock connecting the

Despite the modernisation of cargo handling facilities

on the

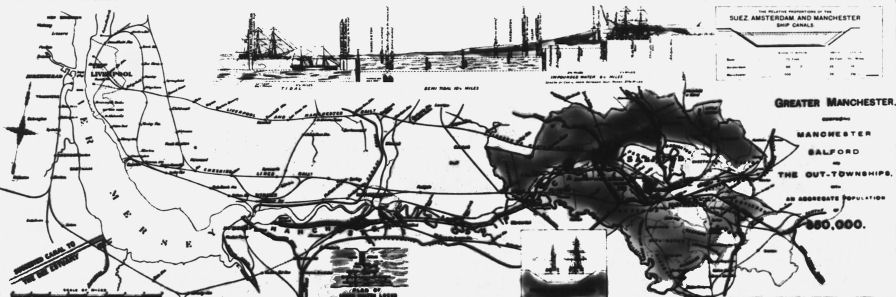

An early map (undated but probably

Rennie’s survey of 1838) showing the route of the proposed ship canal from

Runcorn (not Eastham) to

The map also shows the start of a proposed canal from

During the nineteenth century there were many proposals

for schemes to build a new canal to

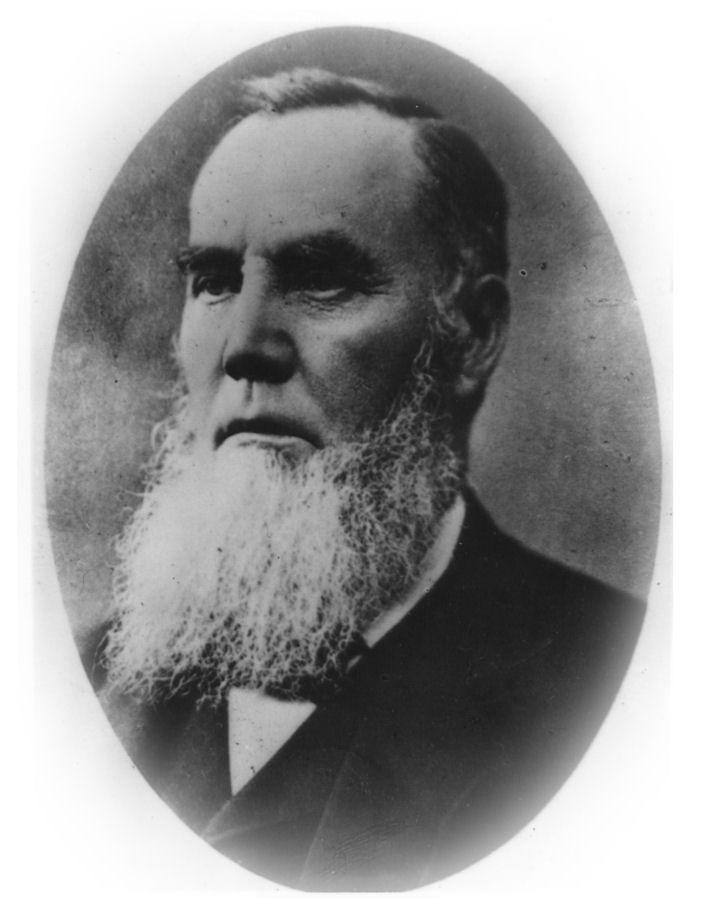

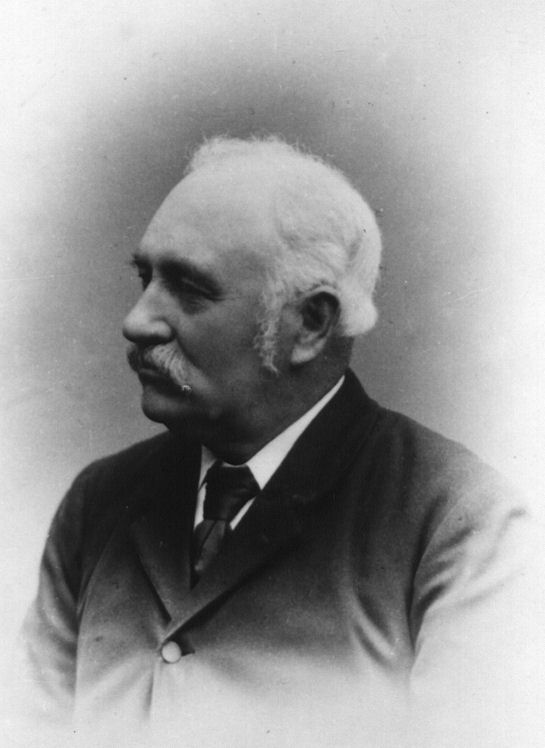

Daniel Adamson... the father

of the

The proposed scheme was for the building of a ship

canal from Eastham on the Wirral bank of the River Mersey estuary to a large

purpose-built dock complex at

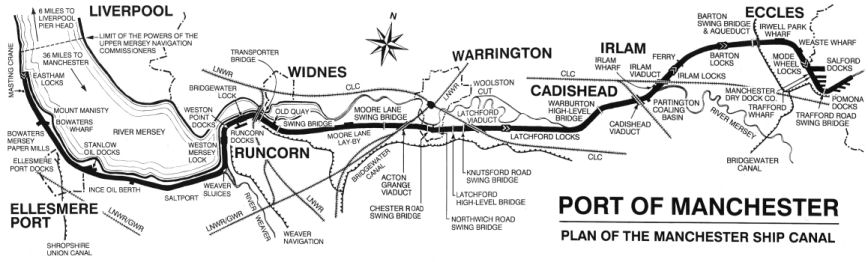

The MSC’s eventual route

This plan caused much excitement and many

people wanted to become involved in a scheme that they thought would bring

added prosperity to

The next couple of years were spent on preparations for

the canal’s construction, obtaining the land through which the canal was to

be built, purchasing digging equipment and materials, organising the

workforce, etc. A contractor was

also appointed. This was Thomas

Walker, an experienced civil engineering contractor, famous for the

construction of the Severn Tunnel for the Great Western Railway.

In the Jubilee Exhibition of 1887, a scale model of the proposed

canal was on display and aroused interest from all over the world.

With the preparations well in hand, Lord Egerton cut the first sod of

earth on

The following year, construction started in earnest.

The route was split up into eight sections: 1. Eastham to

These would have been especially beneficial when pushing a wheel barrow

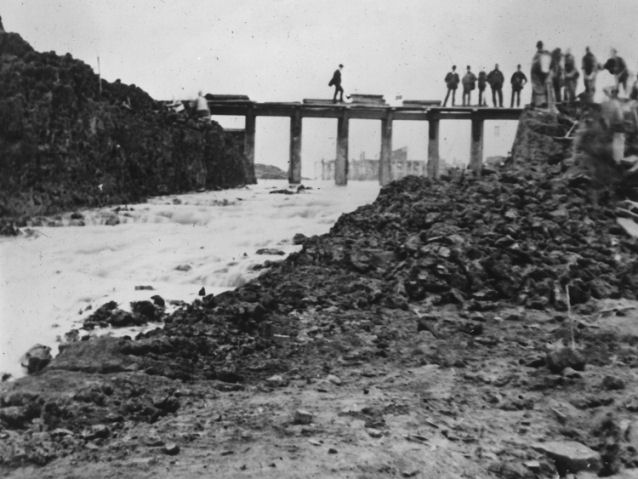

By the beginning of 1889, construction was well in hand

but a long series of devastating blows were to effect the canal’s

construction and threaten the completion of the project.

Daniel Adamson died in January 1889 at the age of 71.

Although his death did not effect construction, it did dampen morale.

Shortly after this, prolonged rainstorms raised the water levels in

the rivers Irwell and

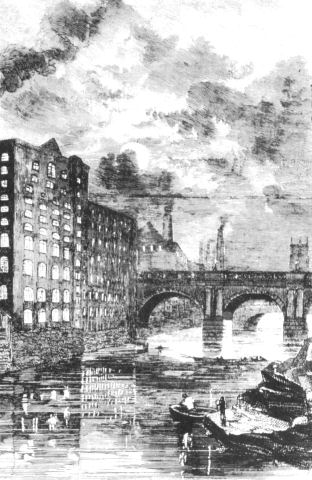

An undated engraving depicting Salford Bridge in Manchester close to the head of navigation on the River Irwell at Hunt’s Bank

In April of the same year the Mersey Docks and Harbour

Company, who had been against the construction of the Ship Canal from the

start, served an injunction for deviating from plans regarding openings in

embankments. The deviation from the original plans, they alleged, would

alter the River Mersey's scouring effect leading to the river channel at

There were some positive happenings in 1889.

In Trafford Cutting, an ancient Runic Cross was unearthed by the

excavations taking place there whilst a dug-out canoe was discovered at

Partington. A large quantity of

Greenheart timber from

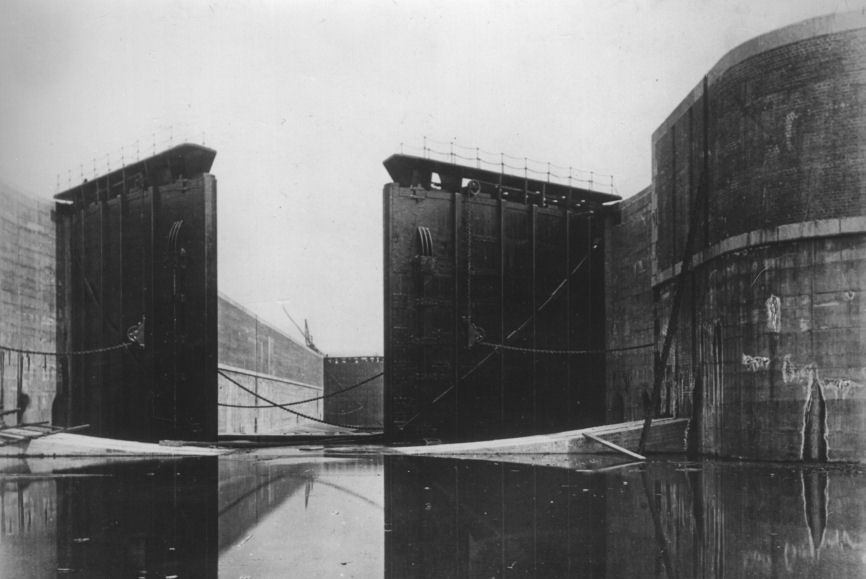

This photograph illustrates the immense size of the entrance lock gates at Eastham

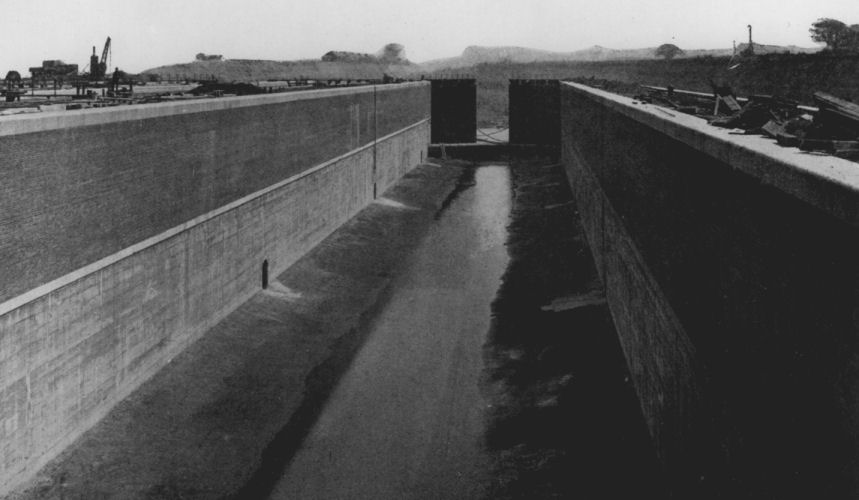

The completed entrance lock

prior to the filling of the canal looking towards

1891 didn’t promise to be any better for the MSC than the previous year. In February an industrial dispute over wages stopped construction. This was soon resolved but by that time financial problems were looming on the horizon.

The prolonged bad weather was causing a great deal of remedial work to be done. This work was extra work was putting a strain on the Company’s financial resources. Consequently, on the 9th March, a special committee meeting with Manchester Corporation was called to request financial assistance. The Corporation agreed to advance £3M to the Ship Canal Company and subsequently promoted a Bill in Parliament empowering them to do so. At a public meeting, Salford Corporation was forced by public pressure to contribute £1M but the decision was denied due to the inability of Salford Corporation to borrow that amount of money.

On

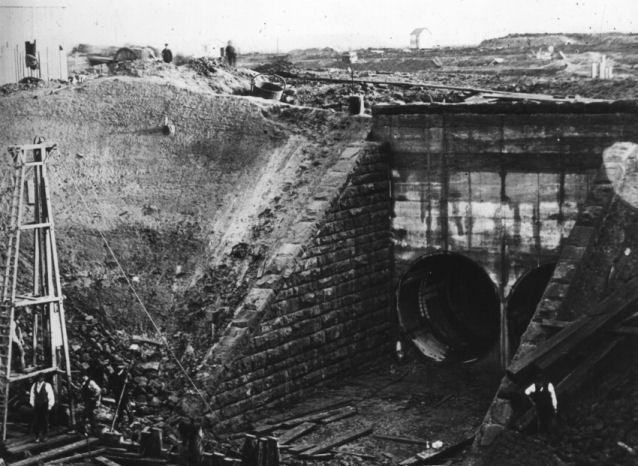

The construction of Pool

Hall Siphon which allows the River Rivacre to flow beneath the MSC close to

Construction machinery was removed on the 18th

June prior to filling. The

actual date of filling this section of the canal with water was kept secret

in order to prevent crowds from forming and creating a safety hazard.

A hole in the embankment was made and as the tide rose, water slowly

entered the canal. Filling of

the section took over a week and when completed the only damage was minor

landslips. However, when the

hole in the embankment was filled-in with soil and hard-core on 11th

July, the embankment was breached by tidal action.

The following day the breach was repaired with boulders but failed

once again. It was eventually

sealed with concrete on the 13th July and no further problems

occurred. On the following day,

The moment of truth, water

is admitted into the canal at

A

completion of the section in

order to gain access to the Shropshire Union Canal Basins at what is now the

|

Weston Point Docks on Note the church on the left which is one of the few churches in the country built on an uninhabited island and the now demolished light house in the right of the photograph |

Delamere Lock gave access to

Runcorn Docks complex as well as the

Victoria Railway Viaduct at Runcorn Gap

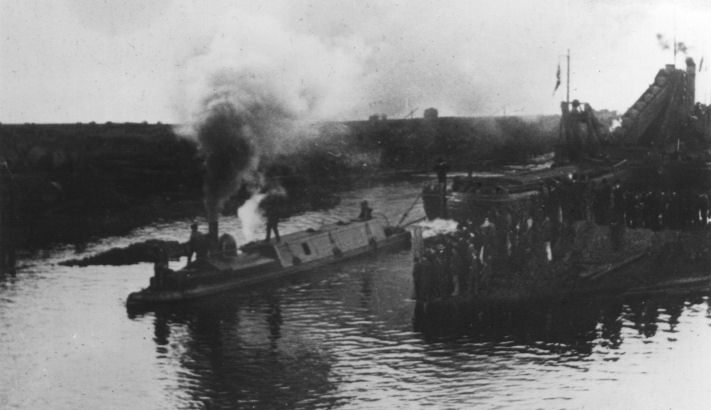

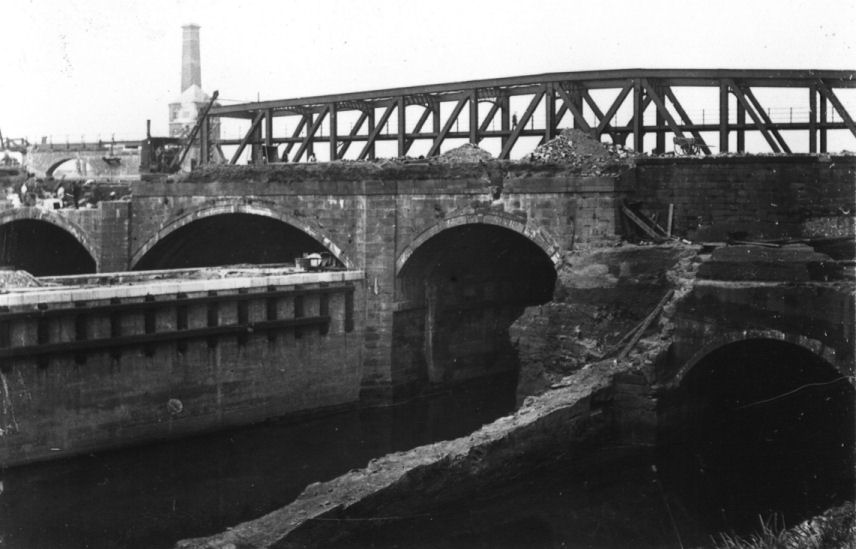

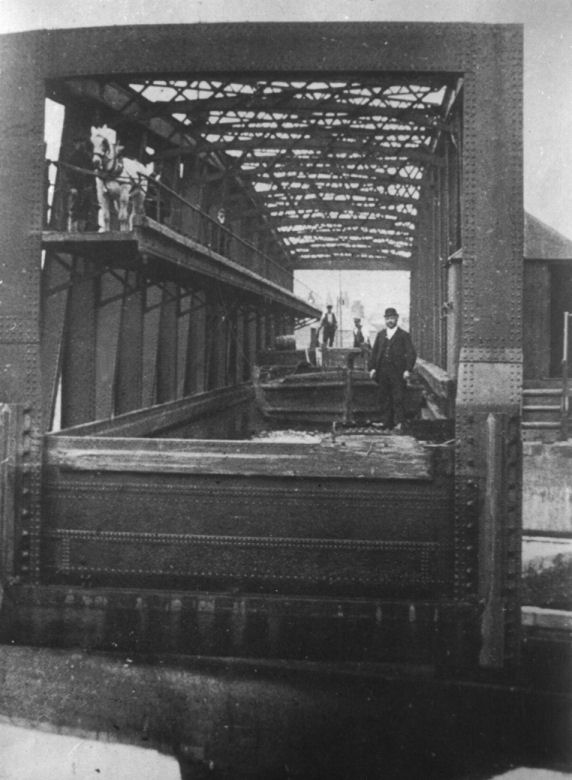

Construction of Latchford Locks. Note the islands in the distance which will form the lock chambers

Elsewhere along the canal, construction work was slowly being completed. On the 1st August, the River Irwell was channelled into Little Barton Cutting. By the 14th September, the Ince Section was completed and filled with water without drama.

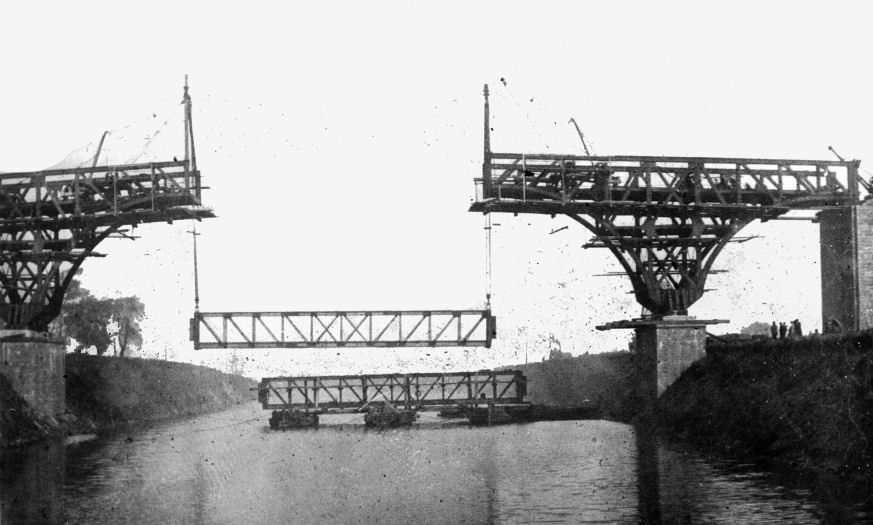

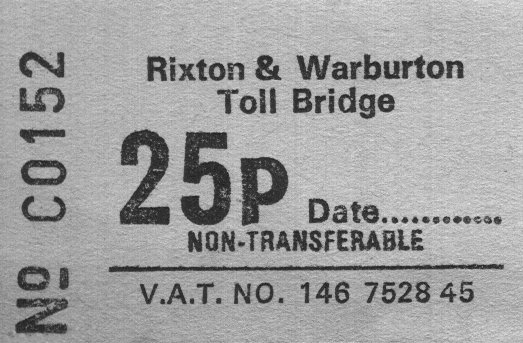

There is more evidence of in-filled meanders at Warburton near Lymm. Here a stone toll bridge across the old Mersey and Irwell Navigation was made redundant when the MSC was being constructed. The bridge lay on a meander on the line of the River Mersey that was cut across to shorten the route. The size of vessels anticipated on the MSC would not have been able to negotiate the meander let alone fit beneath the bridge. The original bridge was replaced with a high level girder bridge almost identical to that at Latchford. Once the MSC was completed the original bridge was embanked and the meander in-filled to become farm land. If the area is visited today the meander can still be seen as can the original stone balustrades on the stone bridge. A toll is still payable today but not to pass over the steel girder bridge but the original stone one!

The original

The same location as the previous photograph today shows the drained river bed as well as an embankment beneath the remains of the bridge

From Warburton High Level Bridge over the MSC can be seen the meander on the right leading to the old bridge

Construction work on

A toll is still payable to

cross

At the end of 1891 another financial crisis struck.

An additional £863,000 was needed to complete the canal. Also,

continuous rain caused the rivers

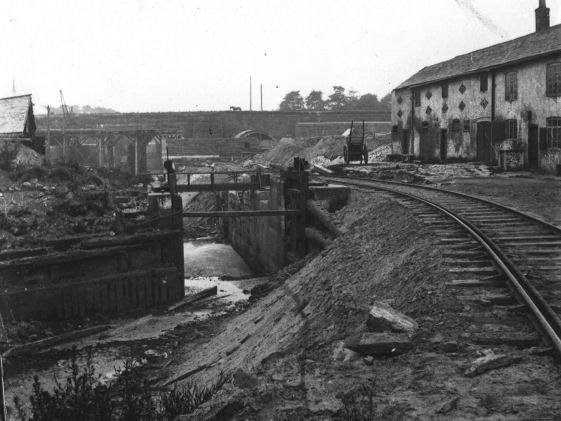

Construction work above

Latchford Locks

By July 1892 the amount of money required to complete the canal was raised yet again to £2M. Manchester Corporation raised its rates to pay the amount. Industrial unrest amongst workers didn’t help matters either but was resolved by raising wages. Cadishead Railway Viaduct at Irlam was completed and the railway company insisted on testing its strength by driving ten railway locomotives over it, weighing a total of 750 tons. Needless to say, the viaduct passed the test with flying colours.

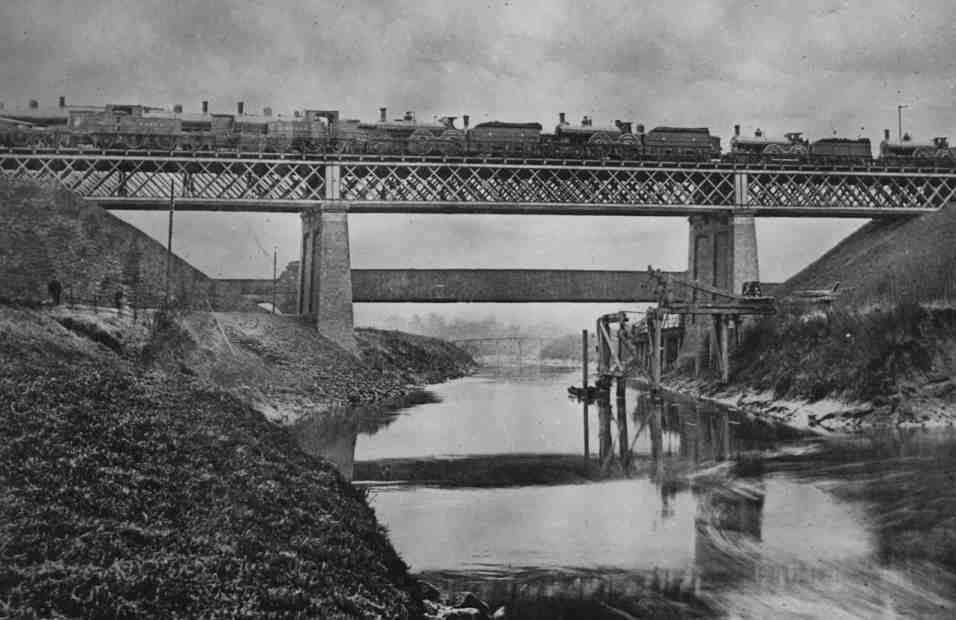

Reputedly Cadishead Railway Viaduct being tested by having ten railway locomotives being driven onto it with a combined weight of 750 tons

The construction of the

An undated photograph showing a narrowboat crossing Brindley’s original Barton Aqueduct.

Note the calm water beneath the left hand arch leading to Barton Lock beyond

From the other side of the aqueduct can be seen the MSC construction railway line

This painting shows the old Barton Lock in the foreground and the aqueduct in the background

In this photograph the lock is being demolished and the railway line constructed on the right

Projected schemes for Barton Aqueduct’s replacement included locks to lower craft to the level of the Ship Canal and up the opposite side (as in the Bridgewater Canal’s original proposal) and a vertical lift similar to that at Anderton connecting the Trent and Mersey Canal with the River Weaver. The latter suggestion is not surprising as the lift at Anderton was the brainchild of the previous engineer for the River Weaver who was none other than Edward Leader Williams (although designed and built by Edwin Clark), the engineer for the Ship Canal. The design that was eventually settled on was for a “swing aqueduct”.

Edward Leader Williams - the MSC's Chief Engineer

The Swing Aqueduct and the proposed swing bridges on

the Ship Canal were to be of similar design to the road bridges that spanned

the River Weaver (also designed by Edward Leader Williams).

The aqueduct would pivot on an island built in the centre of the Ship

Canal and would swing, full of water, to allow ships to pass either side.

The navigation trough would be sealed at either end prior to swinging

by swinging lock-type gates to conserve water.

|

The dimensions of Barton Swing Aqueduct are... |

|

| Length - | 71.6 mtrs (235 feet) |

| Width - | 5.5 mtrs (18 feet) |

| Depth of water - | 1.8 mtrs (6 feet) |

| Total weight - | 1400 tons (800 tons of which is water) |

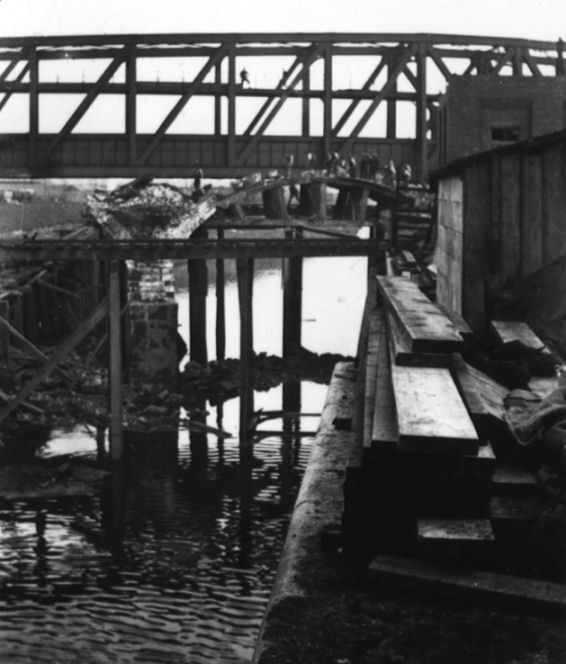

Two photographs showing

the river has been in-filled beneath the left hand arch and accommodates the construction railway.

The centre arch has been removed and replaced by a temporary wooden roadway.

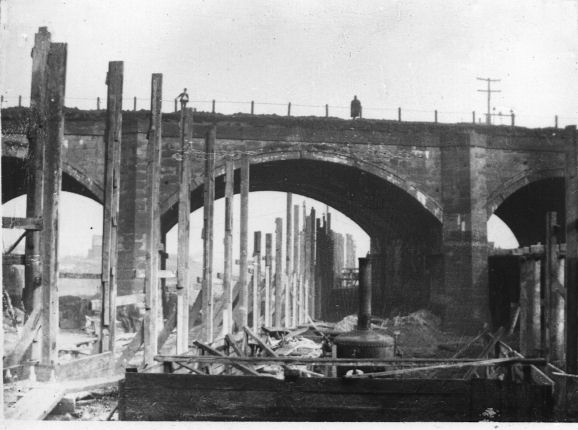

Four photographs showing the

Swing Aqueduct in various stages of construction

Work demolishing Brindley’s

Barton Aqueduct did not commence until May 1893 when the

The weight of the aqueduct is supported by 64 steel

rollers, but when swung, a greased hydraulic ram takes some of the weight

off the rollers.

The swinging

action is achieved hydraulically, being controlled from a tower on the

island that overlooks both the aqueduct and the adjacent

An undated and unusual photograph of Barton Swing Aqueduct being swung complete with barge.

Note the horse on the cantilevered towpath attached to the side of the aqueduct

The completed Barton Swing Aqueduct

Even

though Brindley’s original aqueduct was demolished, there remains a similar

structure on the

Hawthorne Lane Aqueduct at Watch House, Stretford

Barton Aqueduct completed on

Heavy rain in the November of 1893 caused both the

rivers

Construction work close to

the location of

The gigantic scale of the

docks is evident by the size of the workmen in front of the steam crane

With the construction work on the canal and docks at

the

Part of the completed docks

prior to the opening of the canal

At 10.00 on the on the morning of 1st

January 1884, a procession of vessels lead by Mr Samuel Platt’s yacht “The

Norseman” left Eastham bound for Manchester.

The Wallasey ferry boats “Crocus” and “Lupin” had been chartered by

the Ship Canal Company to carry officials, dignitaries and guests and were

amongst the first vessels along the canal after the “Norseman”.

It is coincidental that in latter years the Mersey Ferries have

offered trips along the ship canal and today they are amongst the only

regular craft to use the upper reaches of the ship canal.

Also in the flotilla was the SS “Pioneer” owned by the Co-operative

Wholesale Society and had the distinction of unloading the first cargo

brought along the Ship Canal to

The flotilla of ships lead

by the “Norseman” sailing up the canal on

Even though the ship canal was open for trade, it was

not officially opened until

The official opening

ceremony attended by Queen

This

undated photograph shows the MSC Walton - a

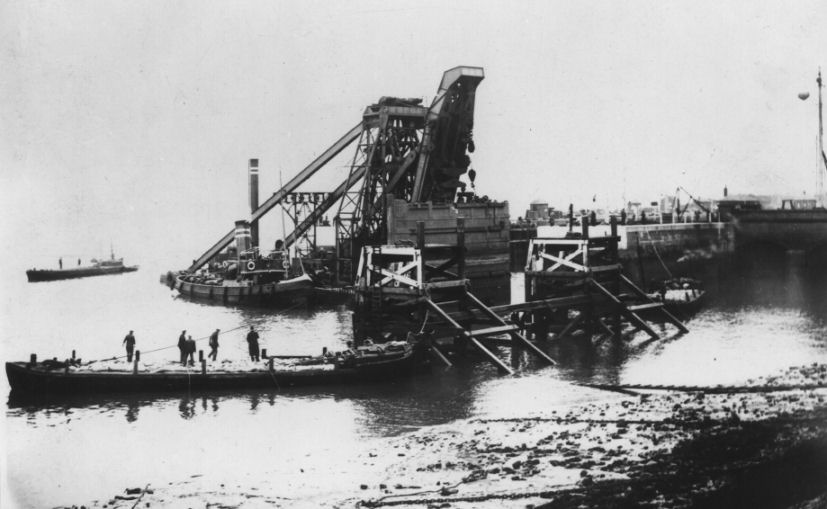

Construction of Number Nine

Dock

An unloading wharf was constructed at

Even though the MSC was deemed a success,

there were craft still

travelled along the lower reaches of the River Mersey in the

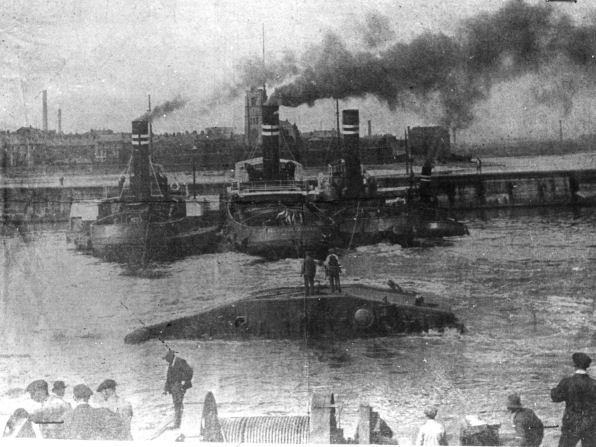

Two photographs of

Manchester Docks just after the opening of the canal

Further down the Ship Canal, at

During the Second World War, the

The ferry boat “

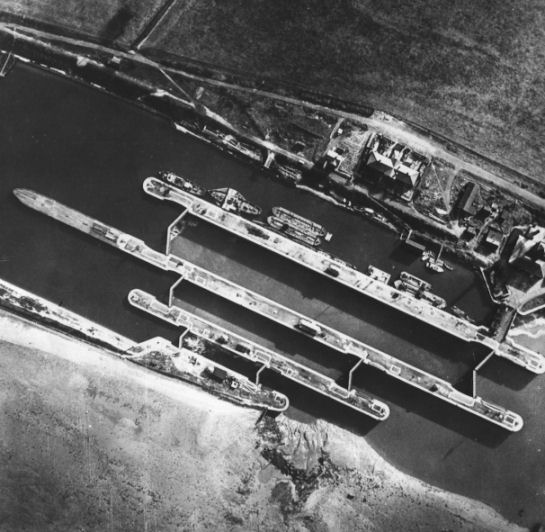

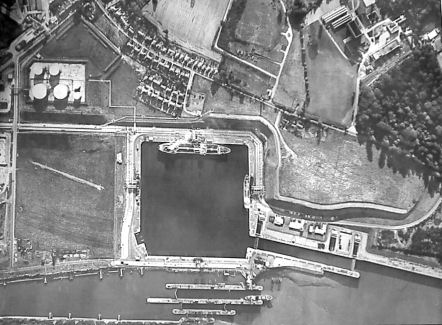

At the other end of the canal, two aerial views of Eastham Locks... the first prior to the construction of the Queen Elizabeth ll Oil Terminal. Note the now disused barge lock being filled. The second craft from the left in the centre of the photograph is one of the paddle tugs used on the canal.

The second photograph was taken after 1951 when the Queen Elizabeth ll Oil

Terminal is completed

Stanlow Oil Refinery continued to grow, as did the size

of the oil tankers that served it.

The Ship Canal was too narrow to allow passage of these larger ships

and plans were formulated to construct an additional dock at Eastham.

The new dock was to be known as the Queen Elizabeth ll Oil Terminal.

Although primarily designed to unload petrochemical oil products it

can also handle edible oil products as well.

Its entrance locks are adjacent to the Ship Canal’s main entrance

locks but there is no direct connection between the Ship Canal and the new

dock except for a water supply regulated by sluices.

Construction work was completed in January 1954 and pipelines were

laid to connect the dock to the oil refinery at Stanlow.

The new dock covers 19 acres, has locks capable of passing ships 245

mtrs x 30 mtrs and is able to accommodating tankers of 35000 tons capacity

making it the largest enclosed oil dock in the

New lock gates being towed

from Old Quay Workshops, Runcorn to Eastham for installation, 1939.

Once at Eastham the new gates are lifted into position by the MSC’s 250 ton floating crane

An oil tanker berthing at Stanlow Island Oil Berth

At Runcorn,

the old Transporter Bridge between Runcorn and

The Runcorn - Widnes Transporter Bridge carried vehicles across the River Mersey and the MSC.

At 1000 mtrs it had the longest span of any transporter

bridge in the world until it was demolished in July 1961

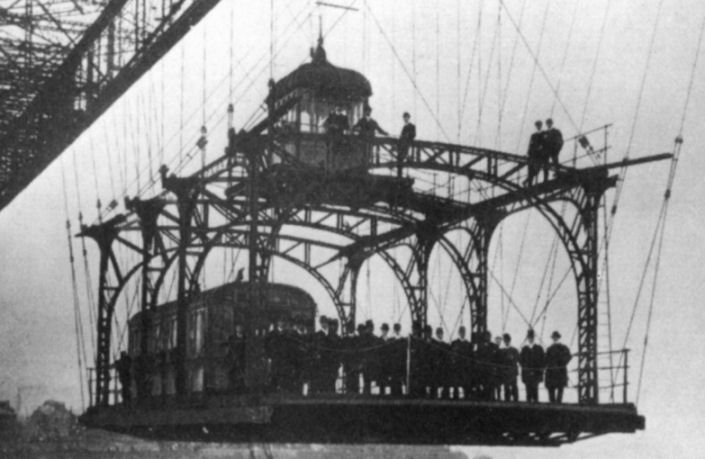

This photograph shows the gondola or “car” suspended by cables from the overhead gantry

There is another transporter bridge located nearby at Crossfields where the tidal River Mersey is spanned

An up-surge of container traffic at

Image ?? - Landscape

A busy scene showing a Manchester Liner in Number Nine Dock

Image ?? - Landscape

Manchester Container Terminal served a weekly Manchester/Montreal cellular ship service of Manchester Liners

Image ?? - Landscape

A heavy transformer being loaded onto “Happy Pioneer” at Pomona Dock.

Much heavy equipment was exported from the

Image 171B - Landscape

A busy night scene at the grain terminal at the end of Pomona Number Nine Dock

A railway along the banks of the Ship Canal from

Runcorn to

Image ?? - Landscape

At it’s peak the Manchester Ship

Canal Company operated the largest privately owned railway system in the

This photograph

shows the Rolls Royce powered Sentinel Diesel Locomotive number 3001 pulling a

rake of chemical tankers.

The following year, 1974, saw the establishment of the

An aerial photograph of

Weston Point showing the River Mersey in the foreground with the MSC behind

it and the Runcorn and

Another aerial shot with the

MSC in the foreground, Runcorn Docks and the two lines of locks of the

Bridgewater House is on the bottom left. Note the sailing ships moored in

the foreground.

The downward trend in shipping along the Upper Reaches of the Ship Canal continued to such an extent that Manchester Docks would close within five years. Bridgewater Estates (including the Bridgewater Canal) and, shortly afterwards, the Manchester Ship Canal, including the Manchester Docks complex was purchased by Peel Holdings in 1984.

When the docks closed, a large-scale regeneration

scheme was initiated.

This

scheme was to convert derelict docks and warehouses into a prestige business

and up-market housing development, starting with Salford Quays in 1985.

The disused docks were converted into water features surrounding the

development and included the construction of a new canal connecting with

marina-style moorings.

Parts of

the dock complex were still in use.

The graving docks, where ships were broken-up for scrap, dismantled a

fleet of Russian fishing vessels and in 1987 the Cawoods container service

to

Salford Quays under construction in 1988 - note the container cranes in the background

Part of the Salford Quays complex... this was Number Nine Dock

A new vertical lift bridge was opened at

Centenary Lift Bridge in Trafford Park

The River Irwell from Pomona Dock

The Mersey Ferries still visit the City of

HMS Bronington moored at Trafford Wharf before moving to Birkenhead in 2002

It is ironic that the history of the area encompassing

Manchester Docks has gone in a full circle.

The area was originally the location of Manchester Racecourse.

It became the docks complex when the Ship Canal was constructed and

is now reverting to leisure use with the establishment of the Lowry Art

Gallery and Shopping Centre in 2000 adjacent to the site of the old Number

Nine Dock, the Imperial War Museum - North

opened in July 2002 at Trafford Wharf and the nearby Trafford

Centre... one of the premier shopping centres in the country, occupies an

area used by industries serving the docks.

The new Lowry Footbridge was constructed to connect the Imperial War

Museum - North with the Lowry Centre and is a vertically lifting footbridge.

This bridge was constructed as a lift bridge should larger craft wish

to pass beneath it into the area surrounding the Lowry Centre.

The area has undergone many changes in character from the hustle and

bustle of the industrial era, the sadness and lethargy of the period when

the docks fell into disuse and the atmosphere of hope as more of the area is developed and new

buildings and amenities are constructed.

It will be very

interesting to see what future developments take place in this area.

In 2000, an unusual visitor to the Ship Canal was spotted at Eastham. A dolphin had followed a ship through the entrance locks at Eastham and was seen following the ship along the canal. It was eventually “ushered” back into the Mersey estuary by staff using a “gig” boat (a small boat used to take ropes from larger vessels) to continue it’s maritime wanderings.

Another unusual visitor to the MSC was the “Super Seacat”

Irish ferry catamaran.

In July

2002 she needed to be dry-docked for maintenance but the lower

The MSC itself is undergoing a period of change as well.

In the past, leisure craft were not allowed to cruise along the

canal.

Now, it is not unusual to

see the occasional leisure narrowboat being allowed to use the canal for

access to the River Weaver at Frodsham, the

Looking down the new line of

locks on the

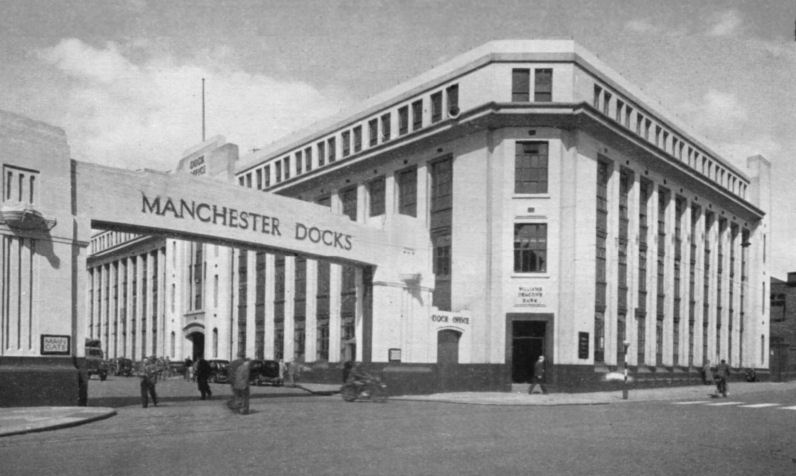

An aerial view of

“Dock Office”… once the

headquarters of the Manchester Ship Canal Company

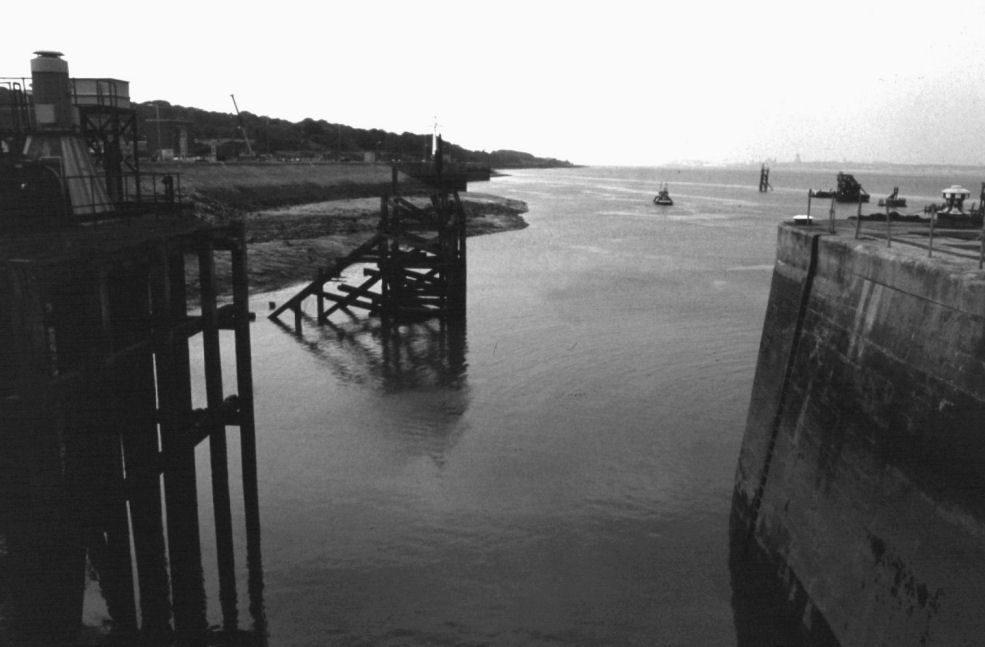

The view from the entrance locks

at Eastham looking towards

The scaffolding structures are called “Dolphins” which are used to guide craft into the locks

In recent years, even with the slowing down of commercial

traffic on the Upper Reaches of the MSC there is still an annual tonnage of

around eight million tonnes of freight with over 3000 annual shipping

movements. A recent development

by Peel Holdings (owners of the MSC) is the construction of a new container terminal near Barton.

This new wharf will unload vessels “fed” from larger ships moored at

the deep water container berth currently being constructed adjacent to

MV "Monica" transporting containers from Seaforth to Caddishead

The telescopic wheelhouse on MV "Monica"

Media City under construction in 2009

Media City Footbridge

Clearance work at the site of the Mersey Gateway - the Second Runcorn-Widnes Bridge in 2013

Mersey Gateway Bridge support under construction - May 2016

Artist's impression of the completed Mersey gateway Bridge - aerial view

(CGI - Mersey Gateway)

Completed Mersey Gateway Bridge

(Photograph - Mersey gateway)

Barton Lift Bridge - March 2018

The Chronology of the

|

84AD |

Fosse constructed at Castlefield by Romans |

|

1697 |

Thomas Patten makes improvements to River

Mersey up to |

|

1712 |

Thomas Steers surveyed the Rivers Mersey and Irwell and suggests

improvements to allow continuous navigation to |

|

1714 |

|

|

1734 |

|

|

1737 |

Scroop Egerton commissioned Thomas Steers to investigate making Worsley Brook and mine soughs navigable |

|

1754 |

Survey to make Sankey Brook navigable by Henry Berry |

|

1757 |

Sankey or |

|

1759 |

|

|

|

Construction commenced on |

|

|

Act of Parliament for Barton Aqueduct passed |

|

1763 |

Connection made between |

|

|

|

|

1804 |

Runcorn and |

|

1821 |

Woolston New Cut constructed |

|

1825 |

Proposal for ship canal from Runcorn to |

|

1832 |

|

|

1838 |

|

|

|

Act of Parliament allowing the |

|

1876 |

|

|

1877 |

Proposal by Hamilton Fulton for a ship

canal to connect |

|

1882 |

|

|

1883 |

MSC Bill passed by House of Commons but thrown out by House of Lords |

| 11/1883 |

Ferdinand de Lesseps (engineer of the |

|

24/5/1884 |

MSC Bill passed by House of Lords but

thrown out by House of Commons on |

|

6/8/1885 |

Manchester Ship Canal Company formed, MSC Bill finally passed by both Houses of Parliament |

|

3/10/1885 |

Bridgewater Navigation Co Ltd purchased

by Manchester Ship Canal Company and a public holiday declared in

|

| 1886 | Act of Parliament passed to pay interest out of capitol in order to raise £8m on the Stock Exchange |

|

1887 |

Jubilee Exhibition contains scale model of MSC |

|

|

Lord Egerton cuts the first sod of

earth in the construction of the |

|

1888 |

Construction of MSC commences in 8

sections - 1. Eastham to |

|

1/1889 |

Daniel Adamson dies at the age of 71. Prolonged rain caused floods in fields and villages due to raised river levels. Temporary dams were washed away |

|

|

Floods in Latchford section between Thelwall and Lymm washed machinery away, destroyed embankments leaving the railway lines suspended in mid-air, between Little Bolton Cutting and Mode Wheel barrier gave way causing 20 million gallons to flood into the works in twenty minutes. In Trafford Cutting an ancient Runic Cross was discovered and another dug-out canoe discovered at Partington. The railway locomotives "Rhymney" and "Deal" collided head-on killing three workmen. |

|

4/1889 |

Mersey Docks and Harbour Company serve

injunction against MSC for deviating from plans regarding

openings in embankments, which allegedly would alter the

River Mersey's scouring effect leading to damaging the river

channel at |

|

7/1889 |

Shah of |

|

|

More rain and gales caused river levels to rise and breach temporary embankments which lead to six miles of the workings to be flooded |

|

|

River Irwell overflowed at Barton |

|

|

Thomas Walker, the contractor, dies aged 62 and legal problems concerning his estate effected working on the Ship Canal. |

|

11/1890 to 1/1891 |

More weather problems affected construction and weather did not abate until January 1891 |

|

|

Industrial disputes over wages affected construction. |

|

|

Special Committee meeting with Manchester Corporation to request financial assistance. The Corporation agreed to advance £3M and subsequently promoted a Bill in Parliament empowering them to do so. At a public meeting, Salford Corporation were forced by public pressure to contribute £1M but the decision was denied due to the inability of Salford Corporation to borrow that amount of money. |

|

|

3000 men worked around the clock to complete the Eastham Section. |

|

|

Regular packet steamer from |

|

|

Work commenced to close the gap in the embankment at Ellesmere Port using concrete. Tugs and dredgers moored in the river adjacent to the gap to act as breakwaters protecting the embankment from tidal damage. |

|

|

Construction machinery removed on

completion of the |

|

|

River water entrance hole in embankment filled-in with soil. |

|

|

Embankment at |

|

|

Breach successfully repaired using concrete. |

|

|

At 08.45 the first passage along Ship

Canal from Eastham to |

|

|

River Irwell channelled into Little Barton Cutting. |

|

|

Ince Section filled without drama. |

| 12/1891 | Another financial crisis strikes. £863000 needed to complete the canal. |

|

|

Continuous rain caused the rivers |

| 1892 | Amount required to complete the canal raised to £1¼M due to winter flood damage. |

|

|

Amount required to finish the canal raised yet again to £2M. Manchester Corporation raised rates to pay the amount. Industrial unrest amongst workers. |

|

|

Barton Aqueduct completed but breach in approach to aqueduct postponed demolition of Brindley's original aqueduct. When breach repaired, demolition of original aqueduct could take place and this section of the canal was completed. |

|

|

Heavy rain caused both |

|

|

|

|

|

Chairman of Salford Quarter Sessions issued a certificate declaring that Manchester Docks were completed and ready to accept vessels. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MSC officially opened by Queen

|

| 3/1895 |

Cotton trade between Southern States of

America and |

| 1898 | Manchester Liners formed as direct result of cotton trade's success. |

| 1899 |

A large flour mill constructed at |

|

|

SS "Chickahomony" brought the first

bananas, mangos, oranges, rum, cocoanuts and logwood.

Immediately after this a two-way service started

between the |

| 1902 |

First transporter bridge constructed at Crossfields

chemical plant at |

| 1905 | New dock half a mile long constructed on the site of the old racecourse and opened by King Edward Vll and the Runcorn-Widnes Transporter Bridge completed |

| 1909 | Water levels raised throughout the whole length of the canal to give a maximum depth of twenty eight feet |

| 1912 |

Second transporter bridge at Crossfields plant

in |

| 1916 |

Excavation work commences at |

| 1922 |

|

| 1927 | Ship Canal deepened between Eastham and Stanlow to accommodate 15000 ton capacity oil tankers. |

| 1933 |

Second (and larger) |

| 1940? | A ship carrying a whale oil cargo shed it’s cargo into Manchester Docks covering the water with a crust of emulsified oil. Boats cleared the spillage working like icebreakers and the workers were paid £8 per day to clear the spillage |

| 1952 | Construction work commences on Queen Elizabeth II Oil Terminal at Eastham which will cover 19 acres when completed |

| 1/1954 | Opening of Queen Elizabeth II Oil Terminal capable of handling ships of 35000 tons and expansion of cargo handling facilities for Colgate-Palmolive at Pomona Docks |

| 1960 | Construction of Barton High-Level Bridge carrying what was then called the M602 Motorway |

| 1966 |

|

| 1970 |

New container berth constructed at

North Quay, |

| 1972 | All Liverpool Docks upstream of the Pier Head closed except for Garston Docks. |

| 1973 | MSC Railway closes and the track subsequently removed except for the section within Trafford Park. |

| 1974 |

|

| 1984 |

Bridgewater Estates and, shortly

afterwards the |

| 1985 | Peel Holdings commence redevelopment of Manchester Docklands starting with Salford Quays. |

| 1987 |

Cawoods container service to

|

| 1988 |

|

| 1994 | MSC’s 100th anniversary celebrated by a commemorative boat rally held at Salford Quays |

| 1995 |

New Pomona Lock replaces Hulme Lock as

connection with the River Irwell and Manchester Docks and

opening of new vertical lift bridge… the |

| 1996 | Centenary Walk, a promenade along what is to be the Lowry Centre was completed. |

| 1998 |

Lowry Centre opens on |

| 2000 |

|

| 2001 |

Proposal to utilise Pomona Dock as a

marina to provide moorings for pleasure craft and the

refurbishment of |

| 7/2002 |

|

| 3/2004 |

Proposals unveiled for a new container terminal in

the Barton area to load and unload feeder ships for the proposed

deep-water container berth at Seaforth on the River Mersey Estuary

opposite |

| 10/2007 | Tug "Daisy Dorado" and barge "Res-V" commence Liverpool to Manchester Container Shuttle Service. |

| 2011 | Media City at Salford Quays completed and BBC followed soon after by ITV move there. |

| 2012 | Planning permission granted for Second Mersey Crossing at Runcorn and construction work commences. Tug "Daisy Dorardo" and barge "Res-V" replaced with MV "Monica"... a purpose built container barge with elevating wheelhouse and MV "Coastal Deniz"... a coastal container ship. Media City Footbridge completed. |

| 2013 | Work commenced on Mersey Gateway (Runcorn) Bridge, Port Salford Freight Terminal, Western Gateway Infrastructure Scheme (including Barton Lift Bridge) and the "Liverpool 2" deep-water container terminal at Seaforth in the Mersey Estuary. |

| 2016 | Port Salford Freight Terminal and the "Liverpool 2" deep-water container terminal completed |

| 16/05/2016 | Partially completed Barton Lift Bridge collapesed |

| 14/10/2017 | Mersey Gateway Bridge completed |

| 2018 | Barton Lift Bridge completed and opened |

Click below to g

or

or select another book below...

![]()

"Canalscape" and "Diarama" names and logo are copyright

Updated 23/03/2018